Be It Known: Women’s Wills Mirroring Anglo-Saxon Times

Anglo-Saxon England was a wealthy world with a gold and silver coinage from the early 600s, beginning in Kent and East Anglia. It had been pagan in the 400s but by the ninth and tenth century it was fervently Christian with a highly sophisticated, international trading system importing fine wine as well as expensive silks from the East destined for the richest folk. However, in stark contrast it could also be an extremely violent, brutal, turbulent world with raiding, fighting and battles not least due to the constant invasions and settlements by the Norse Vikings. At Repton – the Vikings’ winter camp in 873/4 – in the north of England there is a mass grave where at least 264 bodies were buried.

Yet despite or perhaps because of the raids and the wars, strong bonds of family and kinship were forged, as is evidenced in the wills of the women of these times. In their wills, these women weave the golden threads between their ancestors and descendants. Among the earliest wills, one testifies to the strong bond and love between a grandmother and her grandchildren. It has been ever thus through every century into modern times and no doubt will be true hereafter. The same is found in so many other cultures as there is something very precious embedded in the hopes for grandchildren, the younger, future generations of any family.

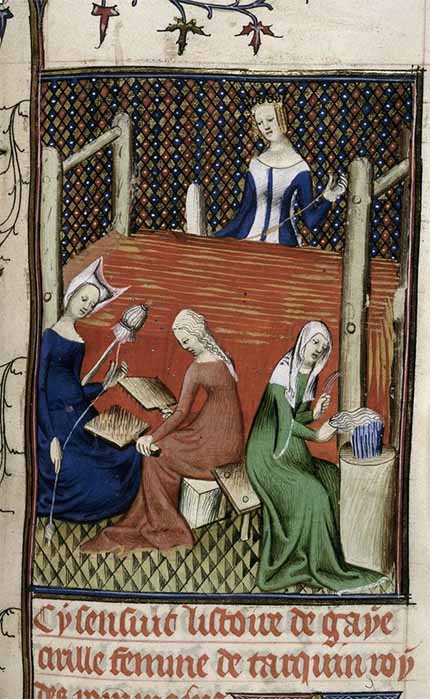

Detail of a miniature of Gaia Caecilia or Tanaquil at her loom, while women spin and card wool. British Library (Public Domain)

Spinning, Weaving and Brewing

The items mentioned in the wills include household goods and furnishings such as tapestries; much of which would have been produced by the women of the household. Professor Gale Owen-Crocker, an expert on all matters to do with Anglo-Saxon clothing, believed most women could probably weave. Every grand estate or farmstead usually had its own weaving and spinning industry which was essential in order to produce clothes, bed linen and wall hangings. One woman’s role in the production of cloth was as a spinster – someone who would spin the threads and yarn which eventually became the woven cloth of wool (from sheep and goats) or linen from flax. It is the “ster” in spinster, seamster and webster (a female weaver) which denote these as women’s jobs. Women in the lower social classes might have been bakers, dairy maids, cheesemakers and brewers who were also known as brewsters. A brewer made beer, yet in later medieval times women were often brewers. Both Brewster and Webster became English surnames.

Offley is close to Lilley, where King Offa of Mercia had a palace. Mercia is one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which included Northumbria, Wessex (the West Saxons), Essex (the East Saxons) and Kent. A unified England only evolved in the early 900s. Then as now, this small village is part of Hertfordshire’s countryside and one still can find wild flax around Lilley. It was a perfect place for the farmers, servants (and weavers) of the King’s palace to cultivate all the flax that was needed. The name Lilley tells its history as it is thought to derive from the Old English “lin” meaning flax.

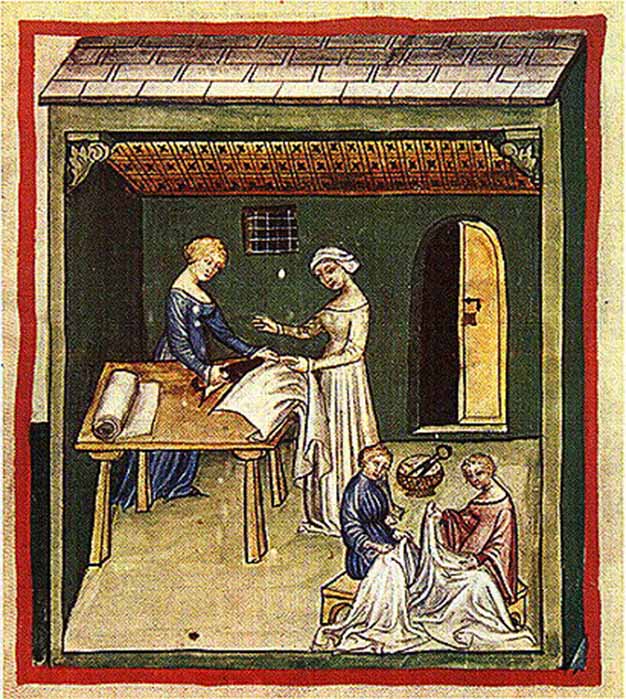

Women sewing linen clothing and bed linen. From the Tacuinum of Vienna (Public Domain)

Clothes gifted in wills include a black tunic, a blue kirtle (a gown or dress) and a nun’s vestment together with linen cloth, a wagon load of wood, a small spinning box, bedclothes, a gold adorned wooden cup, chests and the “best bed curtain”, wall hangings such as a hall tapestry, and an “old filigree brooch”. Jewellery occasionally was a bequest such as a brooch and an engraved bracelet. Linda Tollerton considers that brooches might well be family heirlooms of sentimental value and so passed down through the female generations of a family, as with Gode, elder daughter of Wulfwaru, who received two brooches.

Saxon female graves also contain astonishing pieces of jewellery such as the Harpole necklace made from gold, garnets and precious stones. Dating from around 630/670 and found a few years ago, Harpole is a Christian bed burial in the Midlands which then was part of the kingdom of Mercia. Only 18 bed burials have been discovered so far in Britain, all are female graves where the deceased, dressed in fine clothes and jewels, is laid to rest on a bed.