Anglo Saxon Women’s Wills: Freeing The Enslaved As Testimony Of Piety

Women’s wills which so miraculously have survived from late Anglo-Saxon times deliver some surprising bequests such as the enslaved, which is shocking, but they mirror the societal values which existed at that time. Owning enslaved people might seem at odds with Christian values, and although some enslaved were bequeathed to other recipients, some wills stipulate hey were set free “for the salvation of my soul”. Society was hierarchical with a small number of elite families and limited social mobility between classes. The enslaved were at the centre of the economy in England as elsewhere across the pagan and Christian world. Owning estates automatically implied owning enslaved. The lady Aethelgifu’s will provides insight into the occupations of the enslaved, for instance it mentions a huntsman, a priest and even a goldsmith (and part of his family) were destined to be freed.

Farming on a medieval estate, by Gilles de Rome (CC BY-SA 4.0)

From their wills it is known that women could inherit as well as bequeath land, and family traditions were strongly preserved by aiming to keep land rather than allowing it to go to another family (by bequest or marriage). In King Alfred the Great’s will in 899 he left some of his most important lands, which he had won in battles against the Vikings, to his wife Ealhswith (d.902). However, the will stipulates two things: the first is that the lands could be bought from Ealhswith by the men of the family and that after her death the land would revert to the royal family.

The Enslaved and Prayer Books in the Same Will

Wynflaed, a widow living in the south of England bequeathed enslaved and others who were to be freed – a process known as manumission. Wynflaed owned large estates across four counties, Dorset, Somerset, Hampshire and the Faccombe estate, in Wiltshire which is named in the will. Once a hunting lodge Faccombe was a large farmhouse, possibly a manor house and estate, with a timbered hall and it was a wedding gift (morgengifu) from her husband. Morgengifu or ‘morning gift’ was customary given by the husband to his wife the morning after their wedding. It was often land and mentioned in wills, as it was recognised as hers to leave to whom she wished. Recent excavations at Faccombe revealed a smithy for a blacksmith - a necessity in any Saxon estate - together with kitchens and bake houses. Horse bridles as well as weapons made in the smithy were among the finds discovered during the excavation.

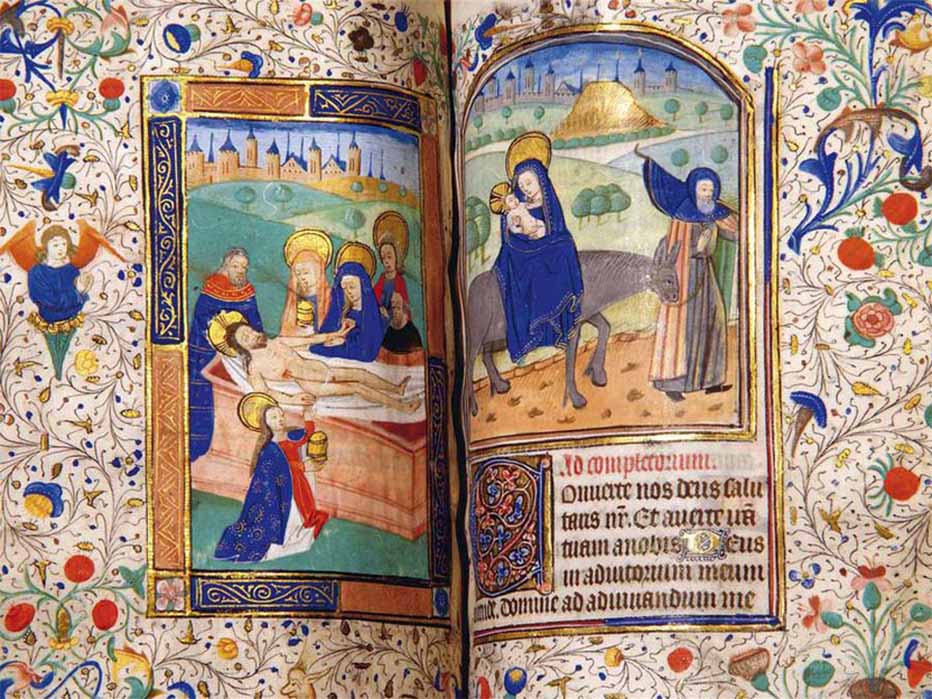

This Book of Hours manuscript, in the collection of Hever Castle, England, is now considered to be Anne Boleyn’s Prayer Book, as was recently revealed with an ultraviolet light scan that revealed a list of “secret names” in the book. Hever Castle and Gardens

Wynflaed left books to her daughter, yet since no details were given so one can only guess at the titles or content. It is generally thought that they were religious gospel or perhaps prayer books, the type of book a pious Christian lady of that time would have likely owned and commissioned for herself. Not only did they convey piety but also a good deal of wealth as these were expensive handmade items crafted in an abbey or scriptorium, adorned with beautiful, richly coloured illustrations. These illuminated manuscripts quickly became family heirlooms (a royal bride in later medieval times might receive one as a wedding gift) and those left to the church in Saxon times were the most valuable bequest. Queen Ealhswith, wife of Alfred the Great, gave her prayer book to Nunnaminster, the Winchester convent she had founded in 899. But secular matters were not overlooked among all the praying, as in the final pages of the Book of Nunnaminster the worldly affairs of the Queen are noted with a list of the land she owned in Winchester.

Lady Margaret Beaufort, by Meynnart Wewyck ( ca. 1510) The Master's Lodge, St John's College, Cambridge (Public Domain)