The Furry Ones Slain And Sacrificed To Bloodthirsty Deities

It is beyond many people to even consider the killing of an animal, the sacrifice of the innocent in the name of a deity, but this was not the case in ancient times, and even in some parts of the modern world, where the killing of what are today regarded as ‘four legged friends’ was an essential part of life and death. When human cultures began shifting from hunter-gatherer lifestyles to agriculture around 12,000 years ago, the traditions of ancient hunting rituals were brought forward and domesticated livestock replaced wild beasts on the blood-stained stone altars of early human camps.

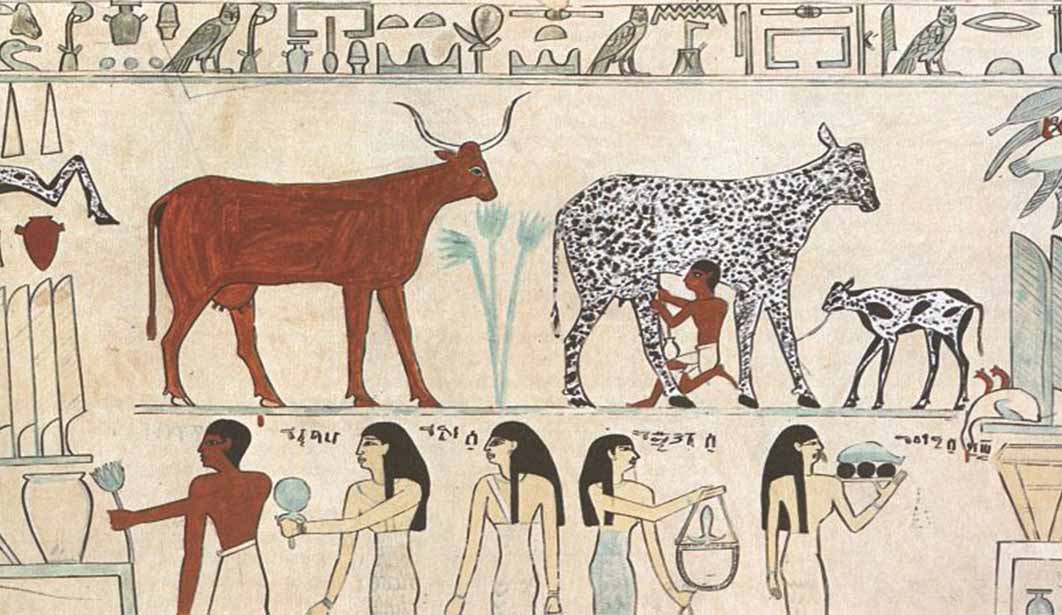

During the Neolithic Revolution the domesticated milking cow was the most sacrificed animal in Ancient Egypt (Public Domain)

The Sacred Cattle Of Nabta Playa

During the early Holocene Period (9,000 – 6,100 BC) Nabta Playa to the west of Abu Simbel in Egypt’s western desert, about 800 kilometers (500 miles) south of modern-day Cairo, flooded annually and a great lake was surrounded by grasslands with an abundance of animals, which attracted nomadic hunter-gatherer-fisher tribes. It is known these people had domesticated animals, farmed, created ceramic vessels, dug deep fresh-water wells and maintained standing stone astronomical observatories more than 9,000 years ago, but they had also developed a rich tradition of sacrificing and ritually burying animals with more pomp and ceremony than they buried themselves.

- From Food to Friend: Prehistoric Exotic and Pampered Pets

- Archaeozoology at Mapungubwe: Let the Bones Speak

- Ancient Canaanites Imported Animals from Egypt to be Sacrificed

Since around 9000 BC the people of Nabta Playa created temporary camps in pastures to feed their domesticated goats and cows, but according to Andrew Slayman’s 1998-book Neolithic Skywatchers, around 7,500 years ago there were notable cultural changes among the peoples of the Nabta Playa, including the sacrifice of calves, goats and sheep. After the beasts were killed they were carefully buried in clay-lined subterranean chambers in the Valley of Sacrifices. The oldest and largest sacrificed animal was a cow that was deposited in a chamber on its side, oriented north to south, with its head facing to the west, then covered with a tamarisk (shrub) roof.

Pottery bowl fragments in the British Museum from early Neolithic Egypt, Nabta (7050–6100 BC) (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Animal sacrifices continued in Africa over the following 4,000 years and in Ancient Egypt the streets and byways of bustling population centers were flowing with warm, deep-red animal blood. Some of the oldest Egyptian animal burials were created by the Badari culture of Upper Egypt between 4400 and 4000 BC and traditionally, Neolithic tribes sacrificed goats and cows and buried them in individual graves. However, by 4500 BC gazelles were being ritually killed and buried at the feet of elite rulers, their families and attendants. Over the next 1,000 years millions of birds, snakes, baboons and hippopotami were ritually sacrificed and buried with humans to help them on their journey in the Afterlife, and by 3000 BC, at the end of the Copper Age, animal sacrifice was a common practice in many world cultures.

Giant Cattle Sacrifices For Feasts In Pre-Historic Ireland

Since the fourth millennium BC domesticated cattle have been a part of the Scottish and Irish landscapes. According to a 2019-paper titled More than meat? Examining cattle slaughter, feasting and deposition in later fourth millennium BC Atlantic Europe: A case study from Kilshane, Ireland, in the north-west of Ireland “ruminant dairy fats have been detected in pottery associated with dates in the 40th-38th centuries BC, on sites that have also produced cattle bone fragments.” Highly-acidic soils have done away with most of the earliest evidence of animal sacrifice but the 2019-study determined cattle had special status strongly expressed by feasting and commensality. This study looked at the 2004-archaeological discovery of 58 individual cattle in ditches around an enclosure excavated at the N2 Kilshane excavation in County Dublin. Dated to the fourth millennium BC according to the team of scientists who excavated the site “this unique assemblage provides important data on early animal husbandry, as well as further insight into the social role of cattle in north-west Atlantic Europe”. How then do archaeologists determine if animals had been sacrificed and their bones ritually deposited, over those that were discarded after being eaten in a non-ritualistic day-to-day meal?