The Arrows and Ardor of Apollo, The Sun God

The sun god Apollo has been identified as the embodiment of the Hellenic spirit, by Scottish classical scholar W.K. C. Guthrie in his 1950 book, The Greeks and their Gods. An eternally youthful deity and a favorite among later poets, Apollo is usually depicted as crowned with laurels that symbolize victory and his attire of a purple robe symbolizes his nobility. A god of multiple roles and significance, as Apollo Pythios he serves as the patron deity of Delphi, an oracular god, as well as the patron of sailors and seafarers, refugees and fugitives. As kourotrophos (the guardian of young people), Apollo oversees children's health and education, as well as their rites of passage to adulthood. Apollo also presides over all music, songs, dance and poetry as the founder of string-music and is revered as the constant companion of the Muses, acting as their chorus leader in festivals.

Apollo, God of Light, Eloquence, Poetry and the Fine Arts with Urania, Muse of Astronomy by Charles Meynier (1798) Cleveland Museum of Art (Public Domain)

Apart from his diversity of functions, there is still more to Apollo than meets the eye. Apollo is also an important pastoral deity as the patron of herdsmen and shepherds. His primary duties included protecting herds, flocks and crops from diseases, pests and predators. Apollo also promoted the formation of new cities and the development of a civil constitution. He was looked upon as the law-giver as his oracles were consulted in a city before laying down any laws and regulations.

Ambivalent Apollo

Despite all his wonderful functions and qualities, ancient Greek tragedies portray Apollo with a completely different characterization. Although the chorus praises him in cultic scenes, the voice of tragic characters usually portray him as an awful god who lacks the very measures generally attributed to his Delphic aspect of moderation (µηδὲν ἄγαν, “nothing in excess”, is even inscribed in the temple of Apollo at Delphi). At the very least, as are all the gods portrayed in tragedy, Apollo is portrayed as ambivalent. Standing beyond the sphere of humanity, these ambivalent gods cannot be comprehended within human categories as they are neither “good” nor “bad”. As a result, instead of being the one to turn to for help in the tragic play, the ambivalent god tends to become a terrible threat to mankind. Apollo in particular forces some characters into tragic situations and then, even when he is the antagonist, seems to be strangely detached, remaining as ever the god who only watches from afar without really participating in the event.

- The Greek God Apollo and His Mystical Powers

- Site in Athens revealed as an ancient temple of twin gods Apollo and Artemis

- Pythia: Oracle and High Priestess of Delphi

Apollo’s character is very similar to that of Dionysus. Like the very dramatic Dionysus, Apollo also seems to oscillate between extreme polarities. He can be both violent and gentle at the same time. He is both dark and bright, near and far, polluting and purifying, infecting and healing, integrating and devastating. Although Apollo’s arrows protect, they also bring deadly plagues. Apollo purged men from their guilt, but he also punished them for it. In the Iliad, armed with his arrows, Apollo is both the healer as well as the bringer of death and disease in a fashion somewhat similar to Rudra, the Vedic god of disease and personification of terror who also favors the arrow as his weapon to inflict destruction. It was perhaps this ambivalence which brought Apollo closer to the hearts of the people. A belief was gradually developed that Apollo was the god who accepted repentance as an atonement for sin, who pardoned the contrite sinner, and who acted as the special protector of those who had committed a crime and were paying the price to society.

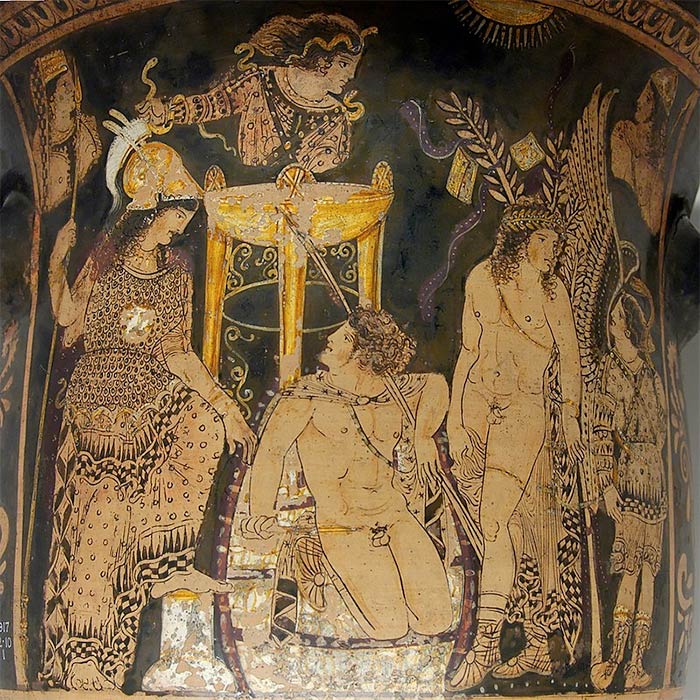

Apollo slays Python for hunting his mother, Leto by Johann Christian Reinhart (1817) (Public Domain)

Apollo’s Archery

Apollo’s arrival in Greece may have followed the destruction of the Mycenaean civilization. A familiar detail on Apollo’s battle with a great serpent is provided in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo composed in 522 BC, when the Archaic period in Greek history was giving way to the Classical period. This may have referred to his conflict with Gaia (the goddess of the earth) which is represented by the legend of Apollo’s slaying of Gaia’s daughter, the serpent Python. As an earth deity, Python had power over the Underworld. The Python was also the deity behind the oracle.