The Battle of Carrhae: A crushing defeat of the unstoppable Roman juggernaut by the Parthian Empire

Ancient Roman invasion forces were considered to be unstoppable juggernauts, but the tables were turned by a formidable Parthian Empire general and devastating tactics. This clash led to one of the most crushing defeats in Roman history.

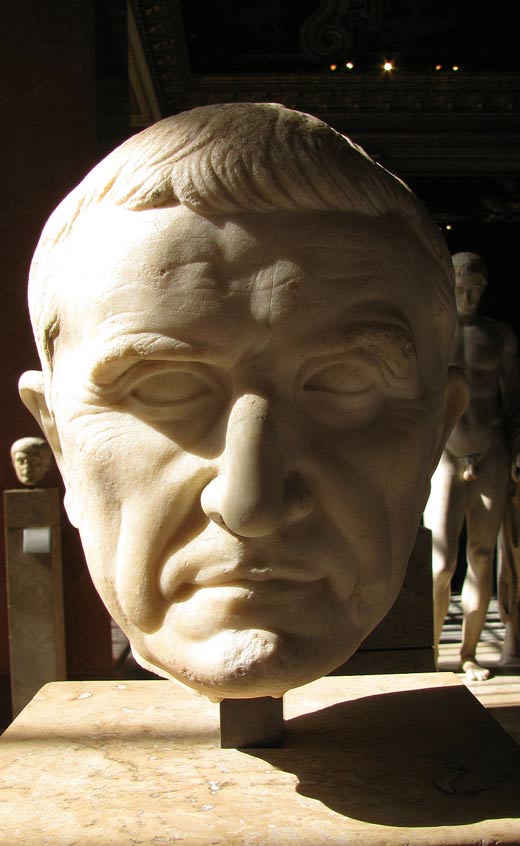

Leading the Romans was Marcus Licinius Crassus, who was a member of the First Triumvirate and the wealthiest man in Rome. He, like many before him, had been enticed by the prospect of riches and military glory and so decided to invade Parthia.

Leading the Parthians was Surena. Very little is known of his background. What is known is that was a Parthian general from the House of Suren. The House of Suren was located in Sistan. Sistan, or Sakastan, “land of the Sakas,” located in what is today southeast Iran.

In 56 BC, Julius Caesar invited Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus to Luca in Cisalpine Gaul (Luca is the modern day city of Lucca in Italy). Caesar requested that they meet to repair their strained relationship, which had been established around 60 BC and was kept secret from the Senate for some time. During this event, a crowd of 100 or more senators showed up to petition for their sovereign patronage. The men cast lots and chose which areas to govern. Caesar got what he wanted, Gaul; Pompey obtained Spain; and Crassus received Syria. All of this became official when Pompey and Crassus were elected as consuls in 55 BC.

Bust of Marcus Licinius Crassus. (Public Domain)

Crassus was delighted that his lot fell on Syria. His grand strategy and desire was to make the campaigns of Lucullus against Tigranes and Pompey’s against Mithridates appear mediocre. Crassus’ grand strategy and desire of conquest and confiscation went beyond Parthia, beyond Bactria and India, reaching the Outer Ocean—easier envisioned than orchestrated.

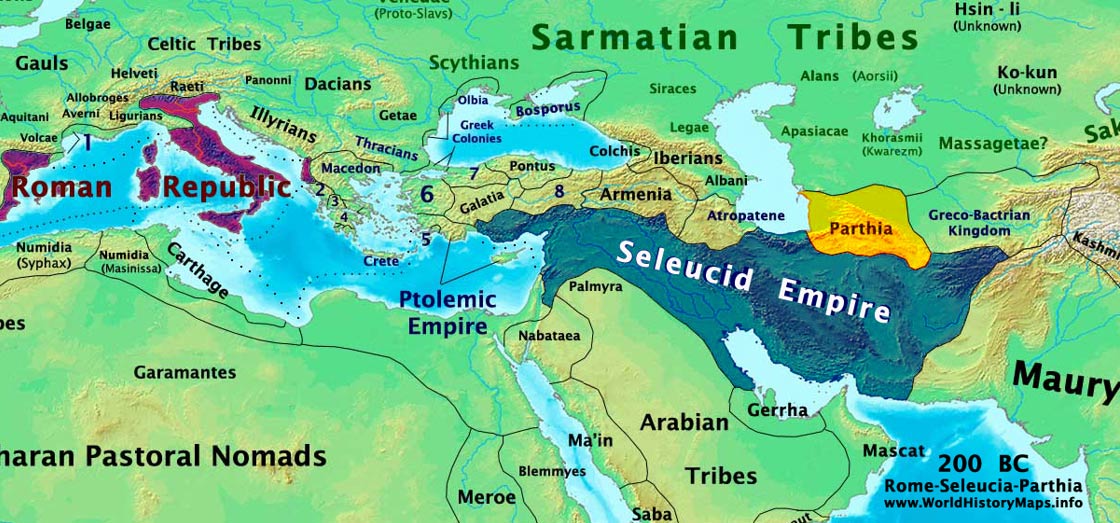

Roman, Seleucid, and Parthian Empires in 200 BC. Roman Republic is shown in Purple. The Blue area represents the Seleucid Empire. The Parthian Empire is shown in Yellow. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Psychological Warfare: Masters of Disguise

Crassus, the Roman general, arrived in Syria with seven legions (roughly 35,000 heavy infantry) along with 4,000 lightly armed troops and 4,000 cavalry. Caesar had given Crassus an additional 1,000 Gallic cavalry under the command of Crassus’ son Publius. As Crassus pushed on, the enemy slowly came into sight. Crassus gave the order to halt, and to their eyes the enemy were “neither so numerous nor so splendidly armed as they had expected.” However, looks can be deceiving.