The Birth of Arthashastra: Ancient Handbook of Science of Politics in India, and Those Who Wielded It

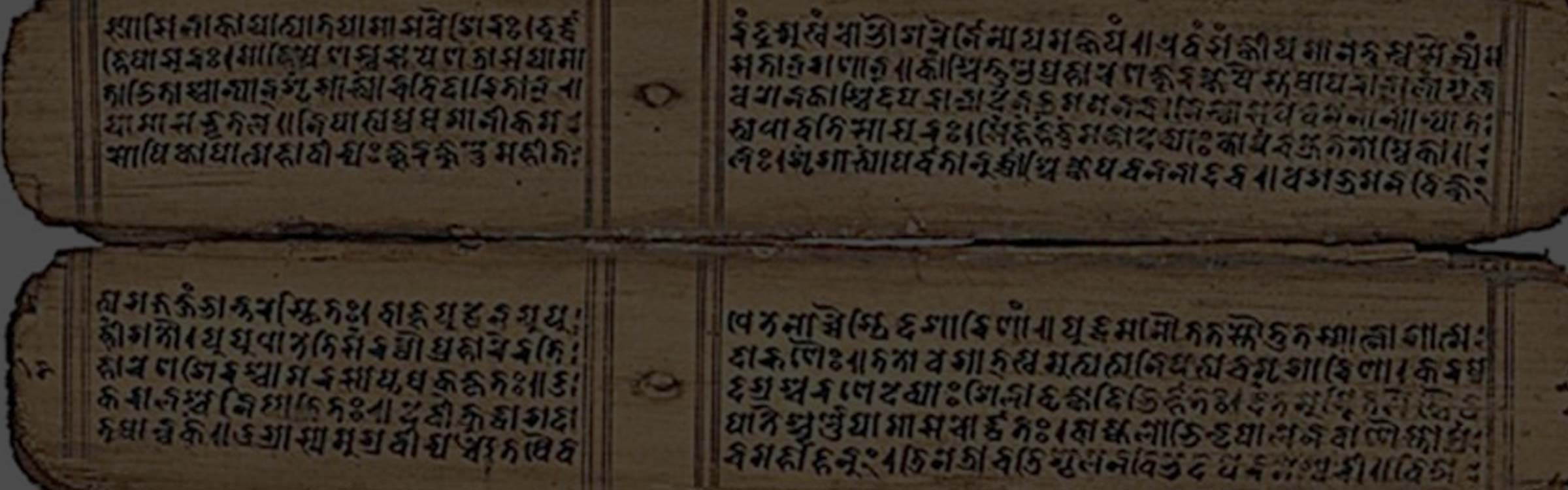

In 1904, a copy of an ancient book which had been lost for more than 1400 years was discovered in India. A modest book written on palm leaves, its outward appearance was proven to be deceiving as the book contained surprisingly detailed information on how an effective government should be run, treating wide-ranging topics from war, diplomacy, law, taxation, agriculture, how to manage secret agents, when it is useful to violate treaties, even when to kill family members.

It was a copy of a book that was written by Kautilya (350-275 BCE), a minister of the Mauryan empire. Called Arthashastra, commonly translated as “The Science of Material Gain”, the book is a major classic of diplomacy even to this day. Within this category, it is one of the most complete works of antiquity.

The Arthashastra. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

his leads to many questions about this extraordinary book’s origins. How did it come about? How did one man have so much detailed knowledge of every aspect of an empire? How could one book make any difference in its time? The answers to these questions bring us to a unique time in Indian history and introduce us to two very strong figures in the philosophy of governance.

A Period of Conflict and Enlightenment in an Ancient Empire

It is useful to understand the period of intellectual history of India in which Arthashastra was written. The two Indian epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, the sacred text Puranas, as well as Buddhist and Jain texts, all mention the ancient empire of Magadha. Like in the ancient Chinese concept of ‘Warring States’, according to Buddhist sources, northern India had the famous sixteen Mahajanapadas (“great realms”) between ca. 600-300 BCE, before the Magadha Empire emerged victorious.

Two of India's greatest empires, the Mauryan Empire and Gupta Empire, originated from Magadha. The two empires saw advancements in ancient India's science, mathematics, astronomy, religion and philosophy. The periods in which these empires ruled were considered by many as the “Golden Age” of India.

It was a period of many ideas and progress. The Upanishadic thinkers and philosophers, as well as the Buddha with his followers dominated the philosophical scene, embodying the transitory and ever changing nature of the empirical world. As far as they were concerned, worldly pleasures were not worth pursuing and were to be shunned. This emphasis on asceticism and renunciation led to reactions from the Lokayata thinkers, who would argue the opposing point.

The Bodhisattva Gautama (Buddha-to-be) undertaking extreme ascetic practices before his enlightenment. (Public Domain)