Bretwaldas: The Early Anglo-Saxon Kings Of Post-Roman Britain

Current literature on the early medieval period in England and the Anglo-Saxons in general, supporting an outdated curriculum taught 40 years ago, postulating that waves of Anglo-Saxons warriors arrived in Britain and pushed the indigenous population to the north and west by killing them and enslaving those who remained, is far from the truth. Recent advances in genetics have revealed a significant continuation of the population. Additionally, archaeology has shown equally significant evidence for continuation of land use, while at the same time rendered little support for any wide-scale destruction and displacement, despite the lurid tales of some of the literary sources such as Gildas, in the early sixth century, and Bede around 730 AD.

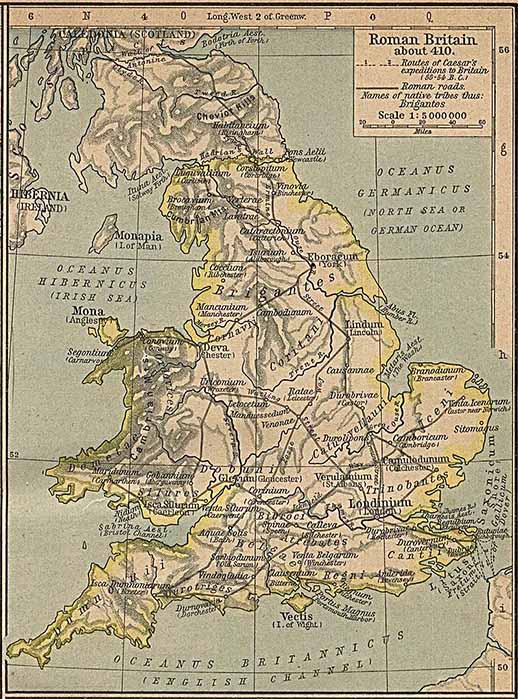

Roman Britain in 410 (Public Domain)

This has led to a vigorous debate about the nature of the Anglo-Saxon take-over. Far from a one-off event, it was in fact a process lasting many decades. At the start of this process, at the beginning of the fifth century, Roman Britain had a functioning civil and military structure which held authority over much of the island of Britain, certainly south of Hadrian’s Wall. In addition, many Britons had a distinctly Roman cultural identity. By the end of the sixth century this had all been swept away. The diocese and provincial structure had fragmented and a number of petty kingdoms emerged, many possibly based on the former civitates and tribal areas. The west and north of the former diocese evolved a distinct Romano-British cultural identity. Ironically the more Romanized regions in the south and east developed a more Germanic culture, however, one should not assume these two groups or regions and areas were homogenous, ethnically, politically or culturally.

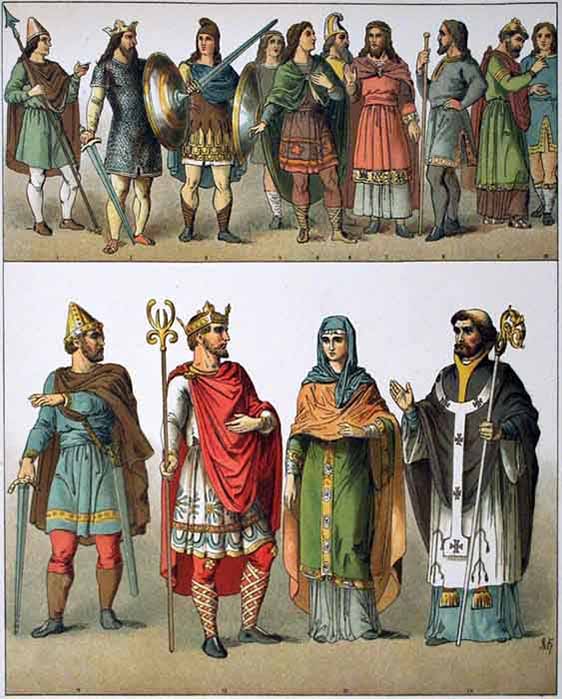

Illustration of Anglo-Saxon society and clothing, 500-1000 AD. ( Public Domain )

The term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ is a late one and applied retrospectively as a combination of influences and events, together with increased levels of settlement, helped create different cultural identities, not just within the indigenous population but also within the various different peoples settling in Britain.

The Comitatus and Seven Kingdoms

In contrast with these different emerging cultural identities an important similarity is often overlooked: The emergence of the war-band as a principal building block of an increasingly militarized society. By the beginning of the seventh century, both the Britons and Germanic peoples came to share the common institution: The comitatus or war-band. Some of the earliest literally sources and sagas illustrate how this impacted on society. Poems such as the old English Beowulf, or Old Welsh Y Gododdin give a vivid picture of Great Halls, shield walls and warriors, in contrast to the apparently still Roman world of Saint Germanus and the Roman General Aetius in the first half of the fifth century.

Bretwalda and his queen listening to a scop telling a tale in a Great Hall, by J. R. Skelton (c. 1910) (Public Domain)