Did Caesar’s Ambition to Conquer Parthia Lead to His Assassination?

In 56 BC, Julius Caesar invited Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus to Luca in Cisalpine Gaul (modern-day Lucca, Italy) in an effort to repair their strained relationship, which had been established around 60 BC, but was kept secret from the Senate. During this event, a crowd of 100 or more senators showed up to petition for their desired sovereign patronages. The men cast lots and chose which areas to govern. Caesar’s wish was granted and he acquired Gaul; Pompey obtained Spain; and Crassus received Syria. All of this became official when Pompey and Crassus were elected as consuls in 55 BC.

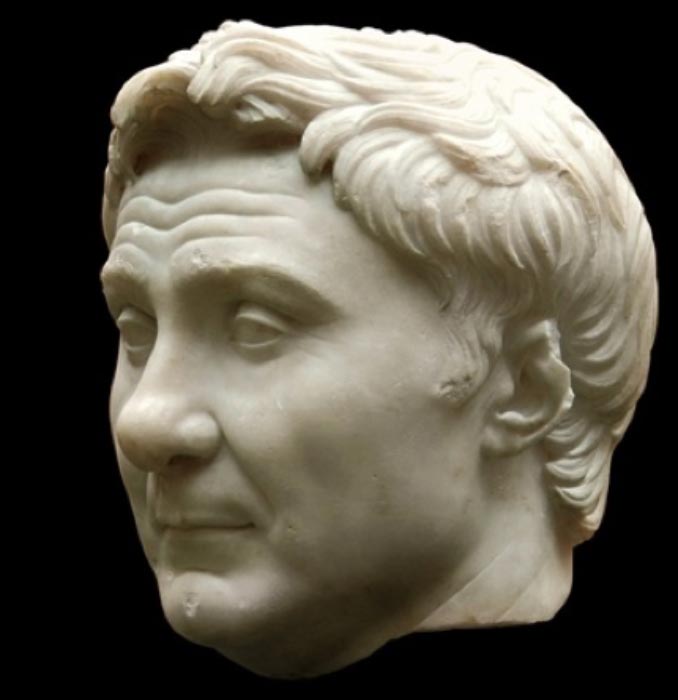

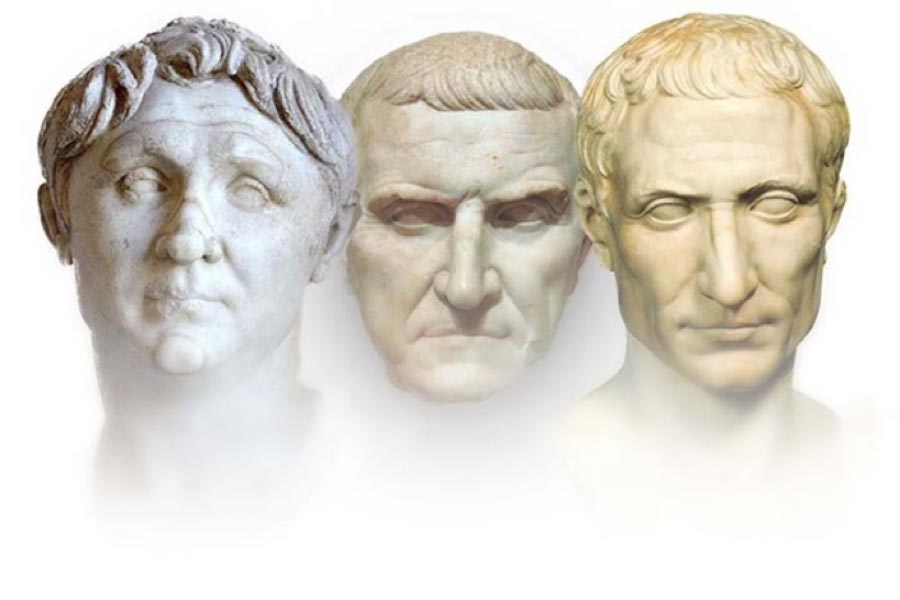

The First Triumvirate of the Roman Republic: Gnaeus Pompeius, Licinius Crassus, and Gaius Julius Caesar (Mary Harrsch/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

Crassus was delighted that his lot fell on Syria as it was his desire to make the two previous campaigns of Lucullus against Tigranes and Pompey’s against Mithridates, appear mediocre. His grand strategy of conquest and confiscation went beyond Parthia, surpassed Bactria and India, reaching the Outer Ocean – a strategy easier envisioned than orchestrated.

Crassus’ Attempt on Parthia

Crassus’ plan to engage a war with Parthia by launching a preemptive strike caused great commotion among the senators. The Senate opposed the plan since Rome had a treaty with Parthia in place. However, men driven by power and ambition have different perspectives. While the Senate was against the idea, Caesar supported it and he sent correspondence from Gaul encouraging Crassus to take on this venture. Thus, Crassus received Caesar’s blessing. The wily Caesar would have approved of such an undertaking since Crassus, a businessman, was not cut of military material. Crassus may have had financial backing to raise and support an army, but he was not a military mastermind like Pompey or Caesar. Caesar would have approved of such an expedition, because with Crassus eliminated in battle, it would leave just two men to fight over control of the Republic.

The Death of Marcus Licinius Crassus by Lancelot Blondeel, (circa 1548 - 1558) Musea Brugge – Groeningemuseum (Public Domain)

As predicted, Crassus met his end at the battle of Carrhae 53 BC as the Parthian forces soundly defeated the Romans. This victory at Carrhae placed Parthia on an equal, if not superior footing with Rome, at least for a brief moment in history. Although the Parthian commander Surena appeared to be a military genius, he was simply better prepared than Crassus, for the Parthians kept track of the events and movements of the Romans through double agents, whereas the Romans experienced a lack or a complete breakdown in military intelligence. Crassus was fighting in the dark and paid with his life.

Pompey’s Plea for Parthia

After the battle of Carrhae, Rome prepared for the anticipated Parthian counterattack. However, it never happened in 50 BC, but in the west, the Great Roman Civil War from 49-45 BC erupted. It was a politico-military conflict pitting Pompey against Caesar. It was during this time that Pompey sought Parthian assistance. Although one would expect Pompey to have avoided any type of assistance from Rome’s nemesis in the east, but he had no choice in the matter, for the structure of his army dictated desperate measures. Pompey had the: “senatorial and the equestrian order and from the regularly enrolled troops and had gathered vast numbers from the subject and allied peoples and kings.” In summary, Pompey found himself in command of a quagmire of experienced and inexperienced forces, all of whom swayed in loyalty, whilst Caesar commanded the legions of the state, a uniformly battle-hardened, and well-armed, professional fighting force. The odds were against Pompey. His military handicap and lack of wealth spurred him to look elsewhere for financial aid to acquire additional forces. In the words of Plutarch: “Pompey had now to plan and act on the basis of existing circumstances. He sent messengers to the various cities, and sailed to some of them himself, asking for money and for men to serve on his ships.”