Catiline’s Ambition: Born And Bred For Roman Consulship

L. Sergius Catilina (106 to 62 BC), or Catiline, who eventually led a failed revolt against the Roman Republic, embodied the virtues and vices of members of his class and generation. Catiline was neither a villain as depicted by Cicero or Sallust, nor a principled popularis (someone who advanced popular causes opposed by the elite) portrayed by some historians. Nor was he a puppet of more prominent figures such as Crassus or Caesar or a bogeyman of Cicero’s imagination. In short, Catiline was one of the Sullani (a follower of Sulla); Catiline was a conservative who was as ambitious as Sulla, but not as lucky. Catiline’s oldest political supporter was the princeps senatus (leader of the senate) Q. Lutatius Catulus who was perhaps the most prominent of the conservative Sullani (optimates). Catiline’s military experience seems always to have been under commanders who were Sullani.

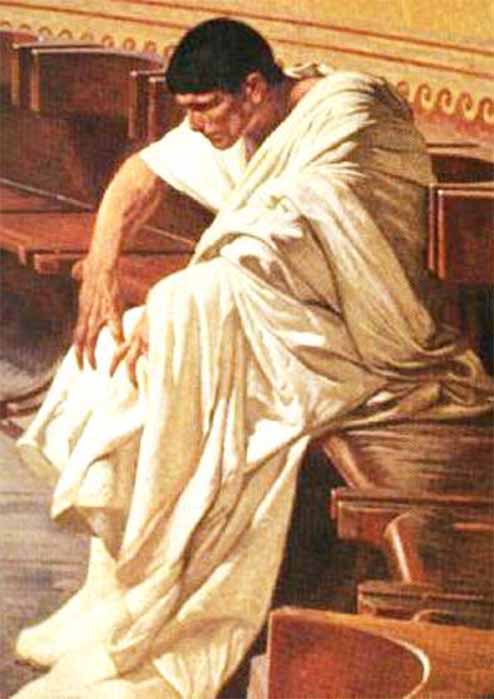

Detail of Catiline in Cesare Maccari's fresco in Palazzo Madama (Public Domain)

There is no evidence that Catiline espoused any popularis (reform) programs during his first campaign for the consulship. Indeed, it was unlikely that Cicero would have considered combining with Catiline in the 64 BC-consular elections had the latter been a popularis, since Cicero was a conservative at heart. It was only after Catiline’s defeat in the consular election for 63 BC that, disheartened by his failure to win when competing with the novus homo Cicero, he began to support popularis programs. Even then, however, he focused primarily on debt reform and relief for the Sullan veterans (his former comrades in arms) who had been given farms in Etruria by Sulla, but who had fallen on hard times for various reasons. Catiline may have advocated some kind of agrarian reform in his second run for the consulship.

It was a second defeat which Catiline attributed to Cicero’s chicanery and to widespread bribery by the successful optimate candidates that led him to the path of rebellion. Catiline did not take up arms to lead a social revolution. Rather, he tried to seize by force that which he believed had been unfairly denied to him. Had he succeeded in his second campaign for consul or in his efforts to seize control of the Republic, he would have advanced the debasement of the currency and some kind of agrarian reform but nothing more. Catiline was driven by pride and ambition, not social philosophy. He could not accept defeat. Catiline was remarkable in terms of his charisma, ambition, and force of will, but not in terms of social thinking or ideology. As Cicero predicted, Catiline chose to die as a rebel rather than live as an exile.

Catiline’s Illustrious Ancestors

“L. Catilina, nobili genere natus (L. Catilina, born of a noble family)” begins the narrative portion of Roman historian Sallust’s Bellum Catilinae. This sentence reveals the most significant element of Catiline’s character: his consciousness of his noble background and his conviction that, as a descendant of a great clan, he was entitled to election to the offices held by his forefathers – specifically the consulship, which was the highest office in the Republic and was held only by those who had first been elected quaestor – an administrative position – and praetor which was a legal position. In his campaign against Cicero, Catiline contemptuously referred to his opponent as an ‘inquilinus’ (a city boarder who lived outside Rome.) He attacked Cicero on the grounds that the latter was a novus homo (new man whose ancestors had never held the consulship) who was not worthy to become consul in the stead of a noble such as Catiline. Sallust claims that Catiline replied to Cicero’s First Catilinarian by saying that it was inconceivable that a man of a distinguished clan such as Catiline would conspire against the Republic or that an ‘inquilinus’ such as Cicero would defend it. Catiline, like every noble Roman, wanted to distinguish himself above all others; his life was dominated by the pursuit of glory.

As a Roman nobleman, Catiline’s life was dominated by the pursuit of glory ( Jamesart /Adobe Stock)

Catiline went through life convinced that he was destined to become consul. His conviction was unrealistic. Those who reached the consulship generally came from powerful and distinguished clans. Many nobles sought the consulship but very few attained it, since only two consuls were elected in each year. Catiline came from a gens (clan) whose members had not reached the consulship for many generations. The odds against his reaching the position were high. He was to face almost as much difficulty in reaching the consulship as did a novus homo, particularly because his family was not extremely wealthy. The wonder is not that he failed to achieve his goal, but that he came so close to achieving it. Nevertheless, Catiline’s family, contrary to the contentions of his enemies, was not poor. Catiline did acquire a mansion on the exclusive Palatine Hill – probably through inheritance. Catiline always satisfied the property qualifications required of a senator. Accordingly, Cicero’s claims that Catiline was consistently on the verge of bankruptcy seem exaggerated.

The Rise and Fall of the Sergii

The Sergii were patricians. The legendary founder of the Sergia gens was Sergestus, the companion of Aeneas. The Sergii played a prominent role in the first century and a half of the Republic. Marcus Sergius Esquilinus was among the second set of decemviri (ten men appointed to reform the laws) in 450 BC.

The first member of the gens to obtain the consulship was L. Sergius Fidenas, who in 437 BC won a bloody victory against the Fidenae and the Veientes. He was twice consul (437 BC and 429 BC) as well as being made a military tribune with consular power in 433 BC, 428 BC and 424 BC. Three of his descendants (the Sergii Fidenates) were frequently military tribunes with consular power: Manius Sergius Fidenas in 404 BC and 402 BC; L. Sergius Fidenas in 397 BC and G. Sergius Fidenas Coxo in 387 BC, 385 BC and 380 BC.