Challenges of Infant Mortality in Ancient Egypt: Disease, Death and Deliverance - Part I

Family came first in ancient Egypt. Be it the royal household or the commoner on the street, the bond between parents and their children was considered sacred. Right through the Old Kingdom period down to the New Kingdom and beyond, various kinds of tokens of familial love have survived intact. However, amulets in the graves of young ones reveal that a dark truth lurked behind the veil of producing many offspring in the hope of living happily ever after. Infant mortality was a curse, no less, which the ancient Egyptians combated in many ways – primarily through magic. The power of faith and prayer was unshakeable.

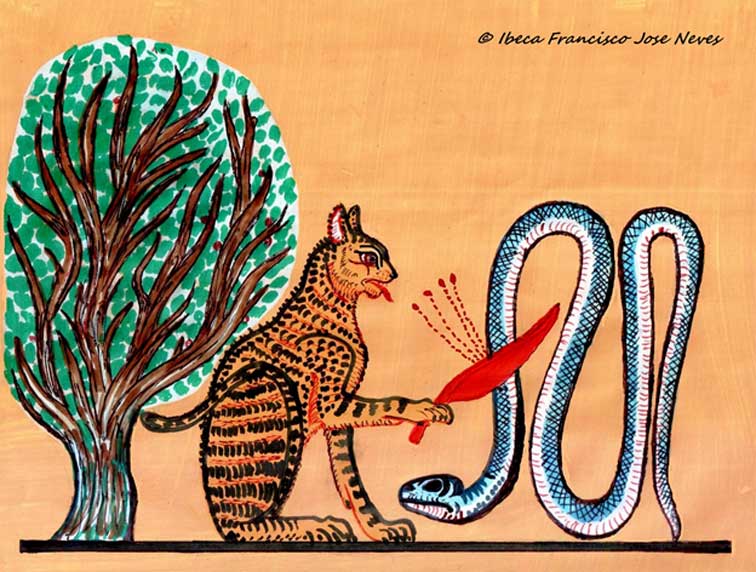

A rare limestone relief from Tell el-Amarna with a sunk relief representation of a squatting woman feeding her child. Death of newborns was commonplace in ancient Egypt. British Museum.

Devastating Infant Mortality Rate

Given the high infant mortality rate, the time of childbirth in ancient Egypt was a challenging period for both mothers and babies. It was considered a blessing of the gods if a child survived the first year; and a double joy if the son or daughter made it successfully into adulthood. It was indeed a sad world, so to speak – one in which husbands who lost their wives spent the remainder of their lives as widowers (if they did not wish to remarry) and children, sans the love and affection of their mothers. Infant deaths were the direct outcome of a variety of diseases that the ancients did not understand and had poor or no remedies for.

Smallpox, for instance, ranked high among the known causes of deaths of babies. With no vaccination available – although rudimentary techniques were employed – the situation was always dire. Also, the (often) improper diets of pregnant ladies, especially among the poorer classes of society, that meant a lack of essential vitamins and minerals, put mothers too at great risk. To compound the issue, matters got out of hand during the periods when the annual Nile floods did not materialize. With the mother dead, the newborn faced an uphill task in surviving the odds. Feeding a motherless child was one of the greatest difficulties that the ancient Egyptians encountered. The milk of livestock – cows and goats – was the only substitute to natural mother’s milk. How many could afford it? This is where the aunts or other close family members of the baby stepped in to carry out this function and keep the baby well-fed.

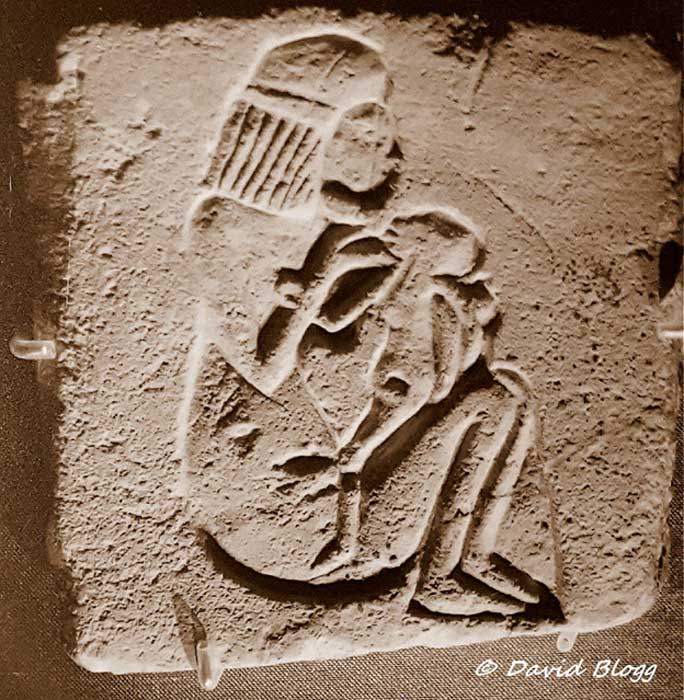

This exquisite alabaster statuette shows Pharaoh Pepi II of the Sixth Dynasty - who ascended the throne as a mere child - sitting on the lap of his formidable mother, Queen Ankhesen-meryre II. Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Parasitic infestation was a bane in much of the ancient world, and Egypt was no stranger to the disastrous effects. Lice, ticks and fleas that survived on the blood of humans brought about much suffering and deadly diseases and infection. With the Nile being their only source of water, parasites that dwelt in the river inflicted debilitating diseases such as bilharziasis or schistosomaisis. Other kinds of parasites, for example the tape worm, were ingested through undercooked food like pork.

- Infant-sized ancient Egyptian sarcophagus found to contain mummified foetus

- Archaeologists reveal contents of 1,600-year-old Roman child coffin

- Ancient Greek Cemetery Provides a Fascinating Window into Everyday Life and Death

Due to the swamp-like locations around which houses were built along the Nile, scores of people fell victim to malaria each year. Scorpions, crocodiles, snakes and other creepy-crawlies and wild animals made lives miserable for the citizenry. This is where religion, and more importantly, magic, called Heka (HkA), entered the stage and played a major role, for the Egyptians firmly believed that all the evil that befell them were orchestrated by demons and vile spirits.