Gods, Goats And Cheesemakers In Ancient Times

During a trip to France, cheesy pasta dishes were served to America’s President Thomas Jefferson. Enthralled by the dish, the president went on to have both the pasta and Parmesan cheese imported to his plantation, and served the very first macaroni and cheese in the United States at a state dinner in 1802 to the apparent delight of the guests except for one, the Reverend Manasseh Cutler. The reverend may have mistook the pasta as onions as he described the dish as “a rich crust filled with the strillions of onions, or shallots.” In short, he did not like the dish. Nevertheless, this state dinner made Jefferson famous as the man who introduced ‘Mac-and-Cheese’ to the American population, in addition to his many other more obvious claims to fame.

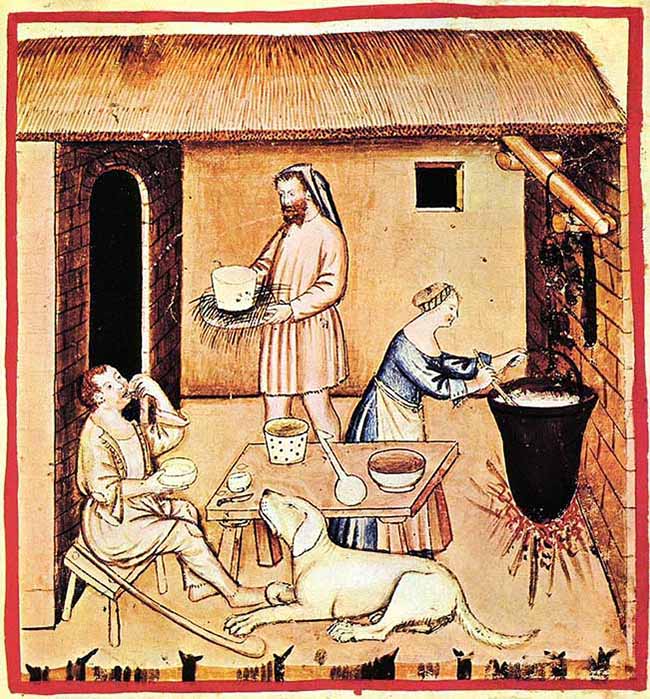

Cheese-making, Tacuinum sanitatis Casanatensis (14th century) (Public Domain)

Pasta and cheese recipes had been around for at least 500 years by the time Jefferson introduced it to the United States. Pasta and cheese casseroles were already mentioned in the 14th-century Italian cookbook, Liber de Coquina (A Book about the Kitchen), which included a Parmesan and pasta dish. A cheese and pasta casserole known as Makerouns was also recorded in the Forme of Cury, a 14th-century medieval English cookbook. The dish was created with fresh, hand-cut pasta sandwiched between melted butter and cheese. Although one cannot necessarily directly trace Makerouns to a previous Italian document, the dish would have been one of the culinary currents during the International Gothic, a period of vibrant cultural exchange in Western Europe that saw a massive travel of artists and artifacts in the large aristocratic network. Perhaps closer to Jefferson's time is the first modern recipe for macaroni and cheese, which appeared in Elizabeth Raffald's 1769 recipe book, The Experienced English Housekeeper. Her recipe calls for a Bechamel sauce with cheddar cheese that is mixed with macaroni and baked until golden.

A Sumerian scene showing milking cows and making dairy products. From the facade of the Temple of Ninhursag at Tell al-'Ubaid (2800-2600 BC) (Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Cheese In Ancient Mesopotamia

Before its popularity as an essential ingredient of a pasta dish, cheese has been a part of culinary history for much longer. Cheese is mentioned in the Bible, with the most famous story recounting David bringing cheese to his troops before slaying Goliath (1 Samuel 17). Cheese was also mentioned in Sumerian records as early as 4000 BC. Around 3000 BC, the earliest pictorial evidence for cheesemaking or caseiculture was discovered on a frieze at Mesopotamia's Temple. The temple was dedicated to the Sumerian Mother Goddess Ninhursag and was one of the oldest and most important in the Mesopotamian Pantheon. The frieze depicted the transformation of milk into cheese. This would have already given an indication of the importance of cheese and cheese-making in the ancient world.

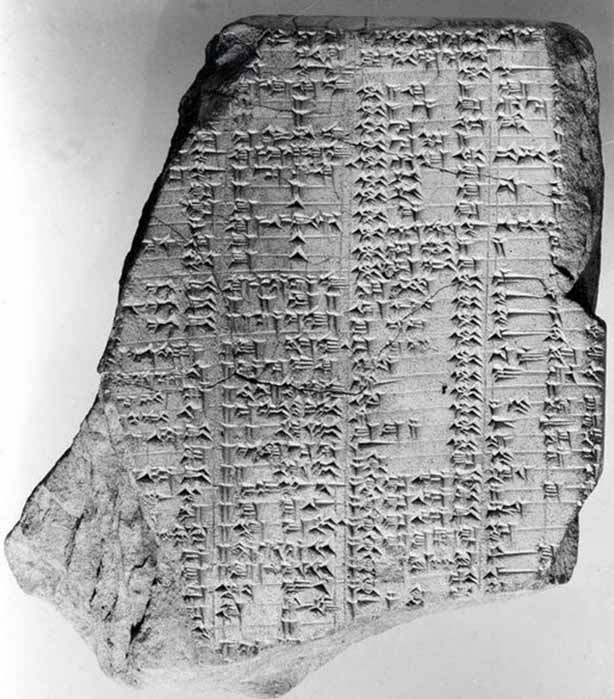

A Sumerian-Akkadian bilingual dictionary, which was written in cuneiform script on 24 stone tablets around 1900 BC, lists over 800 different foods and beverages, including 20 different types of cheese. Well-known sources, such as the Sumerian and Akkadian lexicon found on the Urra=Hubullu tablets (a major Babylonian glossary) and Assyrian bas-relief wall panels show a thriving culinary culture. Fruits named or shown in these tablets and panels include pomegranates, dates, apricots, apples, and pears, as well as radishes, beets, and lettuce. Sheep and goats were both milked and eaten for meat. Cattle, bison, and oxen, as well as wild game also provided additional meat. Wild and domesticated fowl, fish and shellfish of various varieties, and milk products ranging from butter and cheese to yoghurt and sour cream were all enjoyed. These sources depict abundant harvests at home, as well as a thriving foreign trade and a constant flow of people in and out of the empire, which brought additional ingredients and culinary knowledge.

Cuneiform tablet: vocabulary of food and drink terms, Urra=hubullu, tablet 23 (CC0)