Be Merrie All: Medieval Christmas Celebrations

Just as with the appropriation of Pagan sacred sites by Christian authorities, as recommended by Pope Gregory I to St Augustine in the late sixth century, there was a natural tendency in the late Antique and early medieval Christian world to convert previously well-observed Pagan festivals to newly designated religious observances. This usually took the form of imposing Saints’ Days on established festivals, such as the celebration of the apostles Philip and James at the Spring festival of Beltane (May 1) or constructing feast days to mark incidents in the gospels such as The Presentation of Christ and the Purification of the Virgin Mary at the time of Imbolc (February 1), which was a Pagan festival associated with the goddess Brigid (later converted into St Brigid).

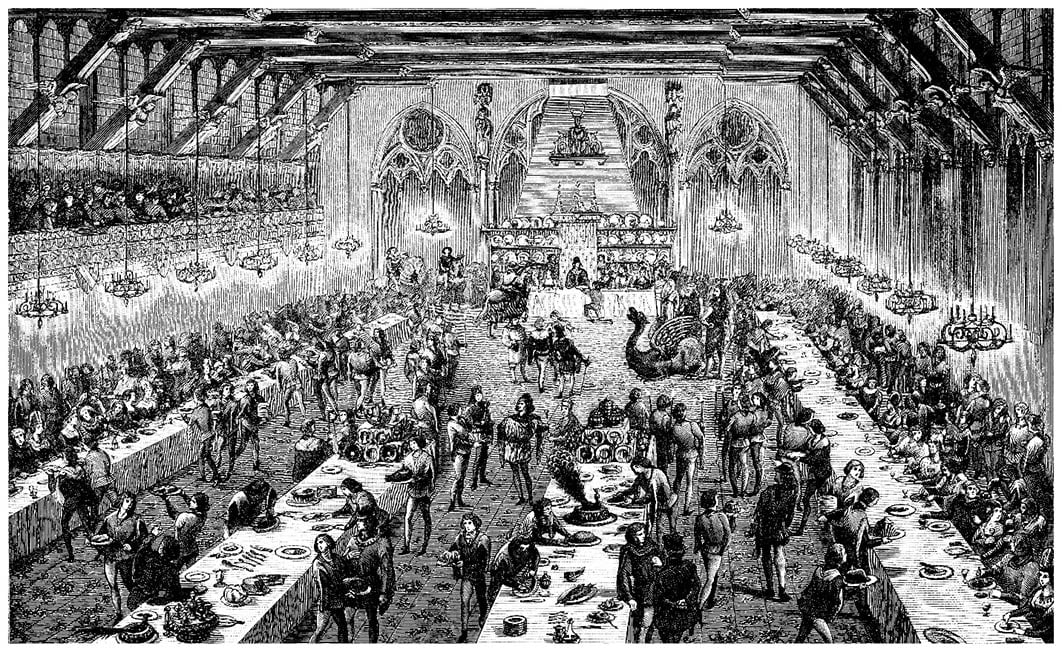

Feast at the French Royal Court (14th century) (Erica Guilane-Nachez/Adobe Stock)

Pagan Festivities And Cristes Maesse

This allowed for a smooth socio-cultural transition, where ingrained calendrical rituals could be maintained, whilst the meanings of those rituals could be transformed. A clear example of this in Celtic and Germanic countries is the transformation of Samhain (October 31) into All Hallow’s Eve and All Saints’ Day on November 1. Samhain was a European-wide, pre-Christian celebration and commemoration of ancestors, but by the eighth century the Church had requisitioned the date to mark its own special ancestors - the martyred saints.

Mosaic of Jesus as Christus Sol (Christ the Sun) in Mausoleum M in the pre-fourth-century necropolis under St Peter's Basilica in Rome (Public Domain)

Likewise, Christmas became a Christian overlay onto previous calendrical traditions. There is no suggestion in either the Coptic or Gnostic Gospels that Jesus Christ was born shortly after midwinter, but by 220 AD the Early Church Father Sextus Julius Africanus had identified December 25 as the date on which Christ was born. This was perhaps an appropriation of the dies solis invicti nati (day of the birth of the unconquered sun), the main festival of Pagan Rome to mark the turning of the year, as light returned from dark. But it was not until the 10th century that Christmas became a major liturgical celebration in Europe, taking over from festivals such as Yule (ġēohol) in Germanic traditions, which dated back to at least the third century AD.

The coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas of 800 AD helped promote the popularity of the holiday (Public Domain)

The first explicit mention of the festival, Cristes Maesse, in Anglo-Saxon England was in 1038, but the fact that William the Conqueror chose Christmas Day for his coronation in 1066 suggests that it had been an important date for a long time before this in England. Even back in 878 AD Bishop Asser had described the Danish army attacking King Alfred’s retinue ‘soon after twelfth night’, suggesting the period of Christmas celebrations had been codified in some form in England from at least the ninth century. Certainly, by the 12th century Christmas had become a principal festival throughout the Christian world, second only to Easter in significance. During the High and later Middle Ages Christmas was celebrated at all levels of society and developed its own specific rituals and traditions, many of which continue to this day.