A Conspiracy of Silence: Are We Older Than We Think We Are?

Generally speaking, when archaeologists find something it's because they are deliberately looking for it. There are exceptions, of course, when someone in the field metaphorically trips over something unexpected in the dark, accidentally discovering a Göbekli Tepe or a Denisovan bone. Then the tendency is to label such a find an anomaly—a one-time accident that doesn't fit within accepted parameters.

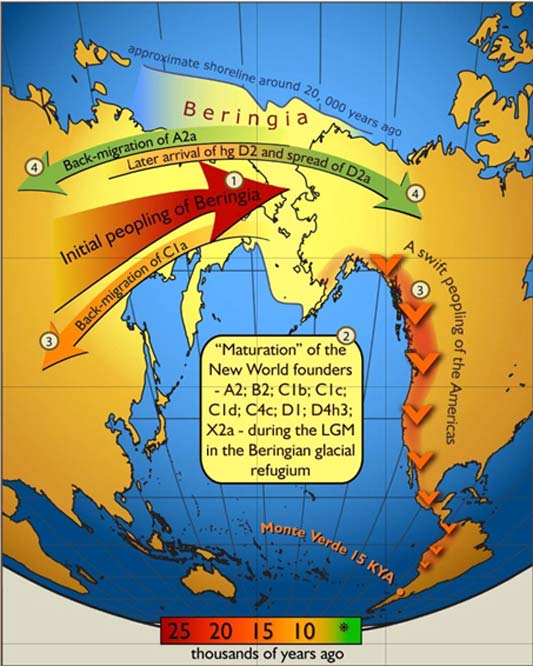

Map of gene flow in and out of Beringia (CC BY-SA 2.5)

When something new turns up that threatens to completely upset the proverbial tried-and-true apple cart, the following argument often ensues: "Where's the evidence? I don't want to see one example. I want many examples!" "Then give me some grant money to go out and find more!" "That would be a waste of money without more evidence!"

The Clovis First Theory

One of the best illustrations for this state of affairs is found in the quest to determine when the first Americans arrived on the continent. Until very recently, ‘Clovis First’ was the accepted dogma. In many classrooms, it is still defended with almost religious zeal.

Forty years ago, the textbooks seemed to have it down pat. They informed us that the most modern, up-to-date geological studies proved that for the bulk of the time modern humans existed, glaciers covered the northern poles and had crawled down as far as what is now the central part of the United States, effectively sealing off what we now call America from any human contact at all. The human race had, by this time, spread out on foot from its genesis in Africa (a theory that had only relatively recently and reluctantly replaced our beginnings in the Fertile Crescent’s ‘Garden of Eden’), and inhabited land from Africa in the south, to Asia in the East, and Europe in the north. With the glaciers locking up so much water, sea levels were much lower than they are now. A thousand-mile-wide land bridge called ‘Beringia’ connected Siberia to Alaska.

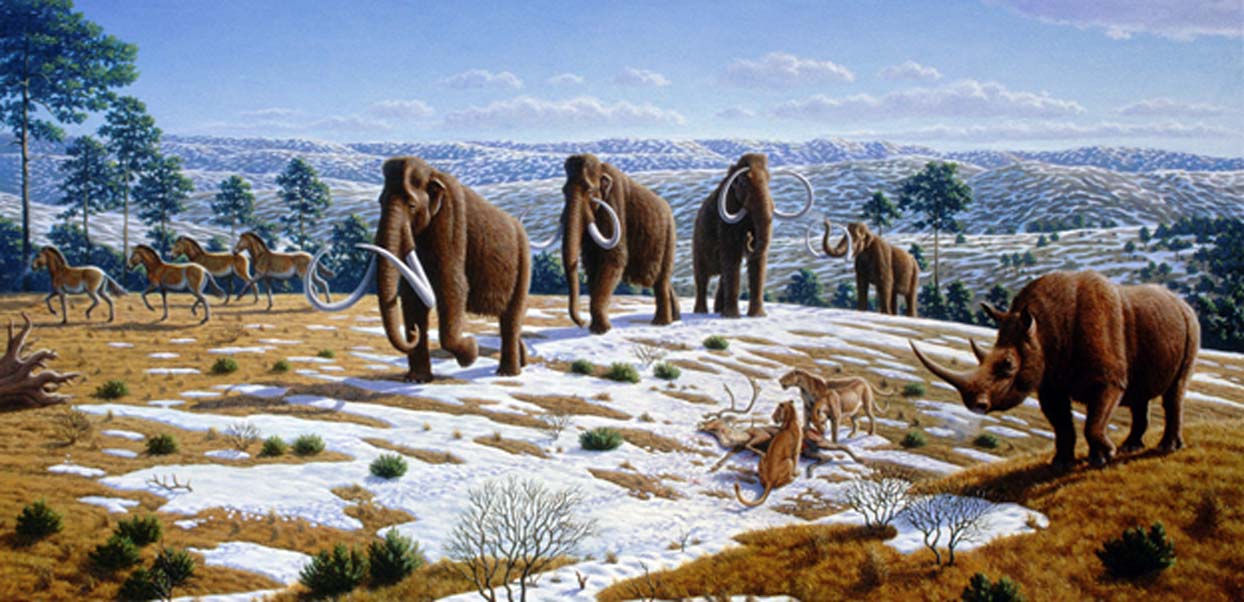

Recreation of a scene in late Pleistocene northern Spain, by Mauricio Antón (CC BY-SA 2.5)

When the ice started to melt, a corridor opened up, allowing humans to follow migrating herds of mammoths and other now-extinct species right into the heart of the virgin American continent. The hunting was so good that human predation, coupled with a series of climate fluctuations and resultant habitat changes, caused the extinction of many of these great species. We knew that humans back then were efficient hunters because a sample of their primary weapon was found near Clovis, New Mexico, in the same site as an ancient mammoth kill. The weapon consisted of a highly efficient fluted spear point named after the location of the find - the famous Clovis Point. Using carbon dating, the mammoth bones were found to be about 8,000 years old. That coincided with the time of the most recent ice-free corridor between Asia and the Americas and was only a short time before the mammoths went extinct. Because this was the earliest clear indication of human activity in America, it was assumed that these were the first people to enter the continent.