The Dakhamunzu Chronicles: Fate of Queen and Country —Part II

Despite the desperate attempts that were made by a queen of Egypt, with the best intentions at heart; the audacious move to invite a foreigner to marry her and take the throne spelled her doom. It would rest on a succession of pharaohs, from the final years of the Eighteenth Dynasty and beyond, to obliterate the legacy of the Amarna kings and all that they had espoused.

A QUESTION OF CO-REGENCY

“The very fact that Smenkhkare was succeeded as coregent by a woman suggests that Akhenaten’s motivation for appointing a co-ruler in the first place may have been something other than the usual concept of elevating the crown-prince to the throne to guarantee the succession and/or allow him an ‘apprenticeship’ under his father. Rather, one wonders whether circumstances had come to demand that Akhenaten needed to have someone to share the burden of rule. Perhaps his own health was breaking down — or he feared the plague that some have suggested was brought to Egypt by those attending the “durbar” and may have caused the death of Meketaten and Dowager Great Wife Tiye, both of whom died soon afterwards —and he feared for the continuation of his religious revolution if he died leaving just the five-year-old Tutankhaten. With an anointed coregent in place there would be an adult in a position to ensure continuity — and become Tutankhaten’s co-ruler and guardian in turn, if need be,” Dodson explains.

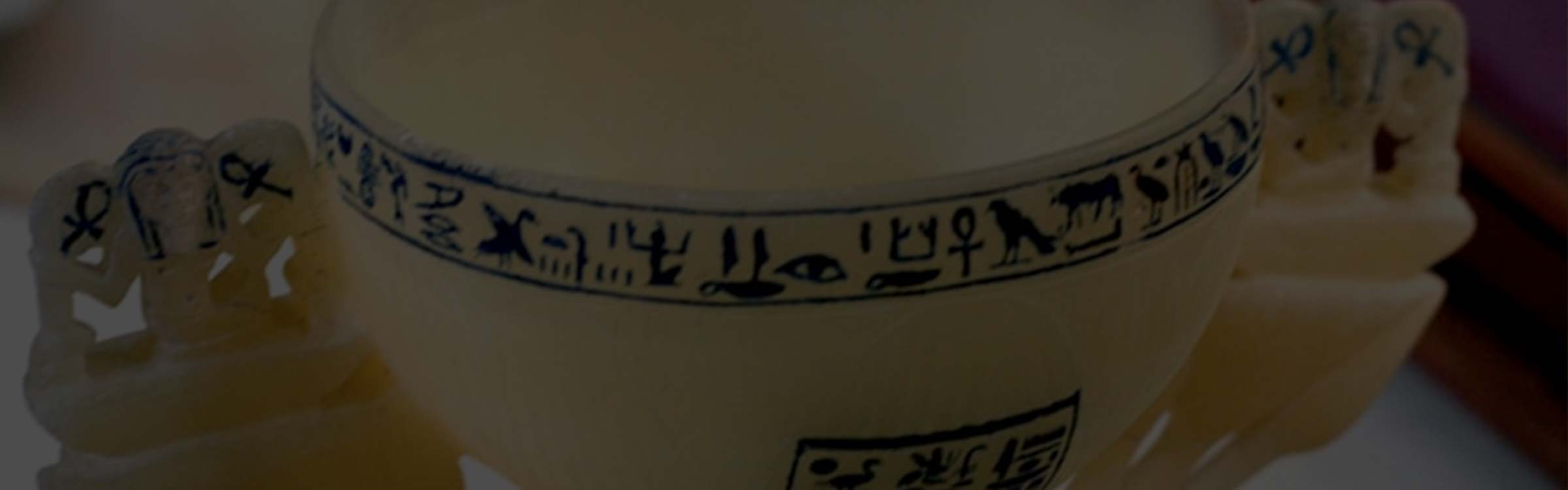

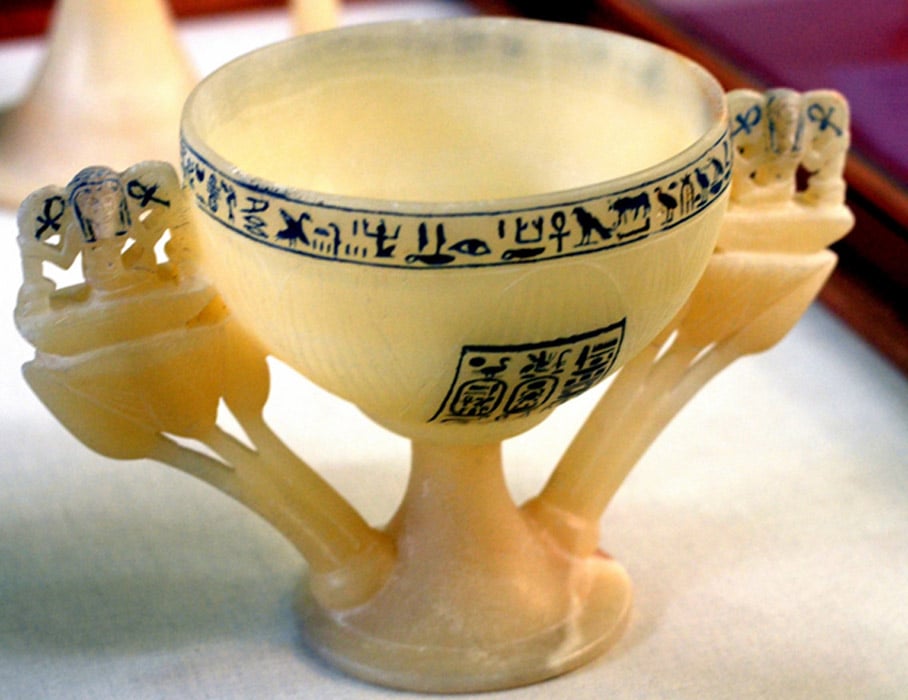

This translucent alabaster Lotus chalice, called the "Wishing Cup" by Howard Carter, was found on the threshold of the Antechamber in Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. (Photo: Heidi Kontkanen)

He concludes that Nefertiti was the mother of Tutankhaten, so after Akhenaten died she continued as regent/coregent to the child king. The Amarna expert proposes that in that role, Neferneferuaten helped guide the counter-reformation in the early years of Tutankhaten and conjectures that her turnaround is the result of her ‘rapid adjustment to political reality’. To support the Nefertiti-Tutankhamun coregency, Dodson cites jar handles found bearing her cartouche and others bearing those of Tutankhaten found in Northern Sinai.

![]()

Far from being the iconic beauty depicted in her famous bust, Nefertiti is portrayed in a rather unflattering manner in this statuette from the latter-half of the Amarna era. Neues Museum, Berlin. (Photo: Heidi Kontkanen)

“On Smenkhkare’s demise, perhaps around Year 14 of Akhenaten, Nefertiti assumed near-kingly titles, becoming King Neferneferuaten during the last year of her husband’s life. The status of Meryetaten in the later setup is intriguing, given her mention as a King’s Great Wife after her parents on the KV62 box fragment. Does this relate to her status as the widow of Smenkhkare, as “wife” of her father — or, perhaps, even of her mother as well? It is clear that the title of “Great Wife” was not simply a designation of the king’s senior sexual partner. Rather, she had key ritual roles, and it was to have someone capable of fulfilling these latter functions that probably lay behind our cases of a father “espousing” his daughters,” Dodson elucidates.