El Caracol Conundrum: Secrets of Chichén Itzá’s Famous Maya Observatory

Standing unique among ancient structures, Chichén Itzá’s enigmatic “Observatory”, El Caracol, may be the world’s most mysterious and distinctive stone monument. It was built by the Maya of the Yucatán, Mexico, over a millennium ago, as part of a larger city, but when the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, they found it abandoned and overgrown by jungle. They made Chichén Itzá their first base in the Yucatán interior, taking over the imposing stone buildings. Sadly, they left no descriptions of them.

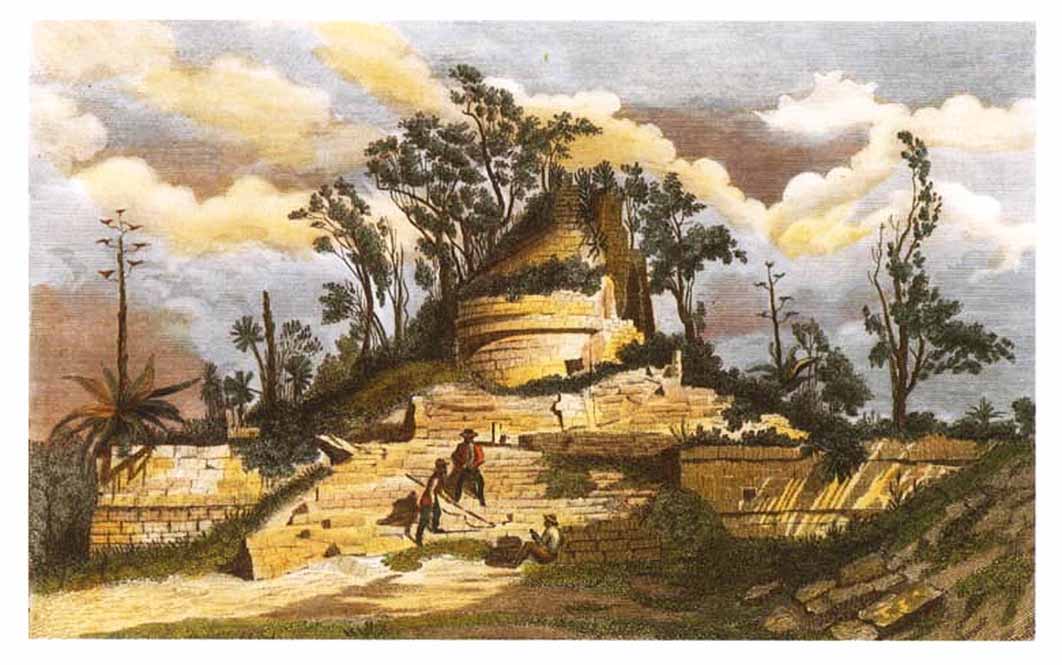

Lithograph of El Caracol. Views of ancient monuments in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan. London: Published by F. Catherwood, (1844)

The first proper description of the Observatory came in 1843 by the American explorer John Lloyd Stephens. In his famous book Incidents of Travel in Yucatán, he called it “El Caracol”, Spanish for the snail, because its internal form resembled a snail shell. He found it in even worse shape than the Spanish had, crumbling and barely resembling the magnificent building it had once been. He summed up his experience with the Caracol: “The plan of the building was new, but, instead of unfolding secrets, it drew closer the curtain that already shrouded, with almost impenetrable folds, these mysterious structures.”

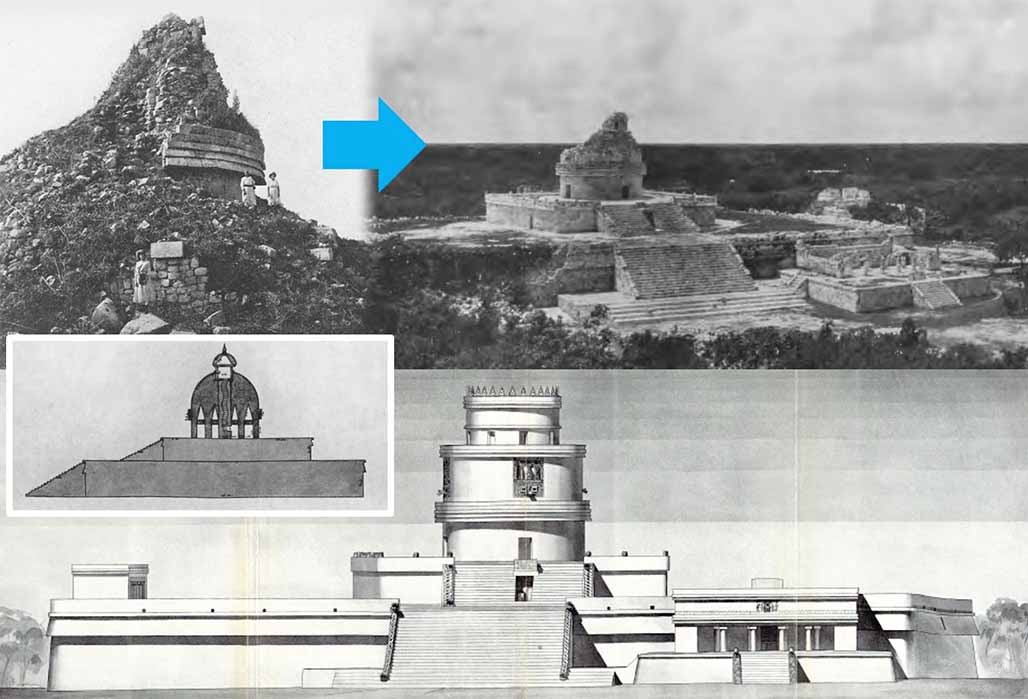

Thankfully, engineers and archaeologists were dispatched from the Carnegie Institute in Washington DC. in the mid-1920s to save the stone tower before it completely collapsed. Through the course of their work, many of the secrets referred to by Stephens were finally revealed. Led first by O. G. Ricketson Jr (1925), then by famed British anthropologist and Mayanist J. Eric Thompson (1926), and finally, from 1927 onwards, by Karl Ruppert, this restoration work included nearly every aspect of the tower and the two platforms upon which it rests.

Four perspectives of the Caracol, clockwise from top left: El Caracol at Chichén Itzá before excavation and restoration, by Gomez Rul; in Morley, 1925; 2) Caracol Repair Completed At End Of 1930 Season; View from the Red House. Stairway of lower platform is centrally located on west side; 3) Recreation of El Caracol at Chichén Itzá by artist J.S. Bolles (Ruppert, Karl, The Caracol at Chichen Izta (sic) Yucatan, Mexico, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1935); Insert: An incorrect drawing of the Caracol by Augustus Le Plongeon from 1875. (Image: Author provided)

Between 1925 and 1931, the team excavated, studied and restored the tower and its platforms to at least a portion of their former glory. In 1935, they published a complete record of their work, providing the most systematic study of the Caracol ever produced. If not for their swift and dedicated intervention, the entire tower may now lie in ruins.

Secrets of the Snail

When it was first re-discovered by Stephens and his travel partner Frederick Catherwood in 1842, the Caracol posed a deep mystery. Here Stephens recounts his first encounter with this mighty edifice: “conspicuous among the ruins of Chichén, and unlike any other we had seen, except one at Mayapan much ruined … it is circular in form, and is known by the name of the Caracol, or winding staircase, on account of its interior arrangements. It stands on the upper of two terraces.”

The excavation and restoration work of the Carnegie Institute focused on the two terraces, their respective staircases, the tower itself, and even the auxiliary temples surrounding the complex. To begin, the staircases leading up to the tower are flanked by menacing serpent heads.