The First Prophets: Inside The Minds Of The World’s Oldest Religious Founders

"Let us be quiet, that we may hear the whispers of the gods." This quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson hints at the subjective experience of religious revelation - the revealing of a higher truth to a messenger by a supernatural deity. Religion is one of humankind's oldest and most important developments, and it has been studied from many perspectives: sociological, neurological, anthropological, and through evolutionary psychology. Despite its often destructive results, religion was originally intended to be beneficial, instructive, and hopeful.

Yet one still knows very little of how the first founders of the world's great religions actually thought. They all claimed to have experienced a religious revelation, beginning more than three millennia ago. What is at the heart of such experiences? Could there be a common mechanism at work in the minds of these great religious founders? This is difficult to gauge, as in many cases one has no reliable accounts of the lives of these individuals.

Moses with the Tables of the Law by Guido Reni (1624) Galleria Borghese (Public Domain)

Nonetheless, this paucity of information should not dissuade one from trying to develop insight into their minds. What if a common psychological mechanism was operating within these pioneering people, a syncretistic mechanism that emerged under conditions of physiological stress and cognitive dissonance? Their minds culminated and reorganized numerous older beliefs in profound new ways, reconciling their conflict and ultimately convincing themselves that they had been visited by a deity with a new message of hope for humanity.

Revelation versus Religious Syncretism

Ever since religions first emerged, they have interacted and joined features to create further religious vehicles. This process is called syncretism and is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as the "attempted union or reconciliation of diverse or opposite tenets or practices, especially in philosophy or religion". Generally understood to act over a long time on large populations, examples include Caribbean Santeria and Japanese Shinto-Buddhism.

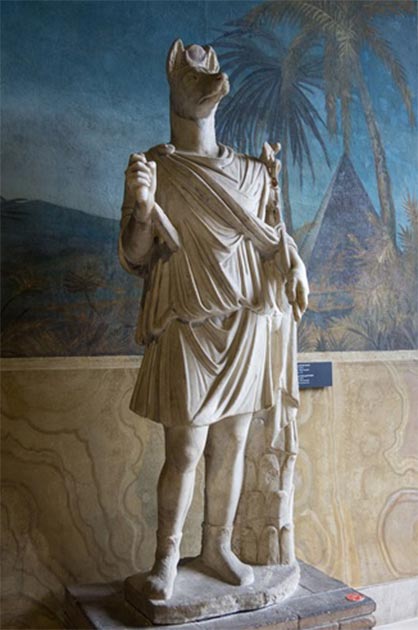

Statue of Hermanubis, (First – Second Century AD) Vatican Museums (Colin / CC BY-SA 3.0)

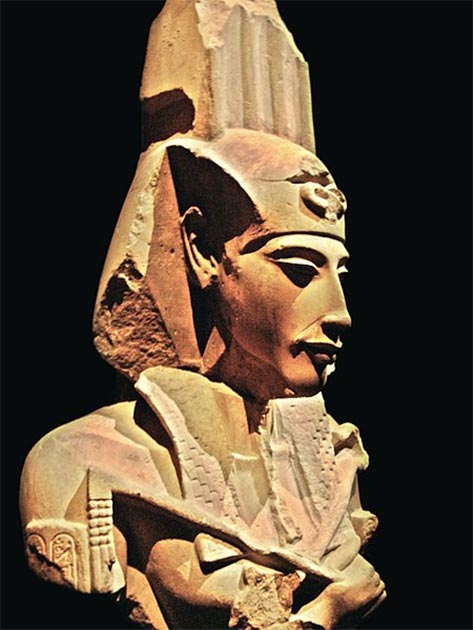

More ancient examples include the combining of the Egyptian gods Amun and Ra, Osiris and Ptah, the Canaanite gods Baal and Zephon, and later Egyptian-Greek gods, such as Serapis (Osiris and Apis) and Hermanubis (Hermes and Anubis). Jesus Christ later took on elements of the Roman sun god Sol Invictus; Gnosticism was a syncretistic blend of Christianity and Persian mysticism, while Sikhism was a blend of Islam and Hinduism. An example of North American colonial syncretism is the famous Our Lady of Guadalupe, a Mexican Saint who overlapped the Aztec mother goddess Tonantzin with the Virgin Mary. Perhaps the world’s most layered syncretistic religion is Bahá'í, which sees itself as the final testament in a succession of prophets going back to the mythical Krishna. This religious syncretism has operated for millennia, and has been an accepted way of easing coexistence with different cultural groups.