When In Rome: Legends - Fact Or Fiction, Does It Matter?

The Greeks exhibited an amazing aptitude for fashioning myths about gods and heroes. Not so the Romans, who failed to produce an independent mythological tradition. But what the Romans did excel at was in shaping legends about the men and women who were instrumental in giving their city its distinctive character in the first centuries of its existence.

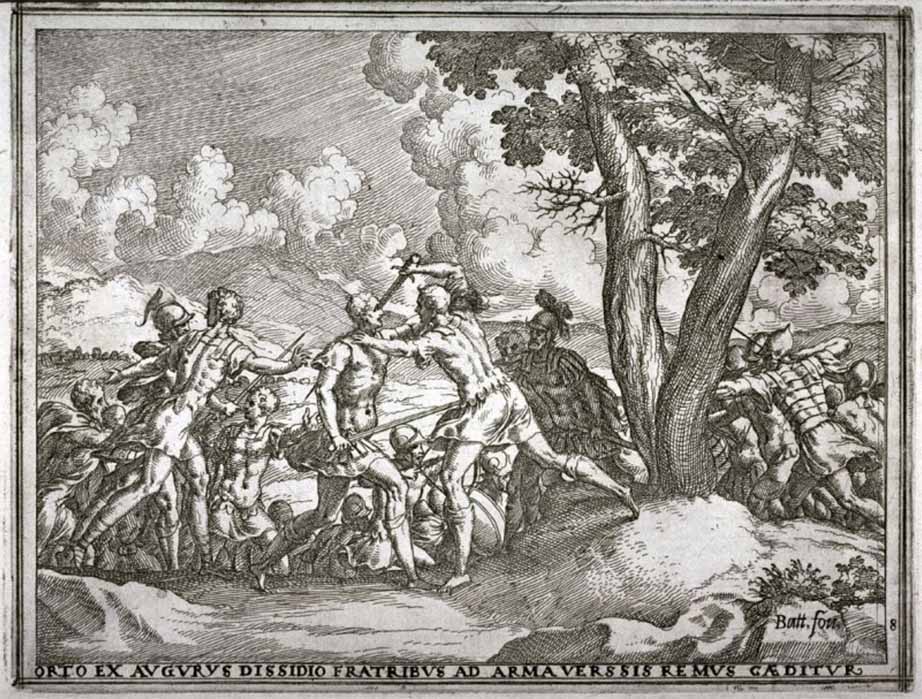

Many scholars eschew the word ‘legend’ altogether and prefer to classify as ‘myth’ any story told over the course of several generations that has significance for the community as a whole. By this definition, whereas a myth is a story set in the remote past, in an imaginary era when the world was still in its infancy and when gods and humans were in direct and regular contact with one another, a legend is set squarely in human history, irrespective of whether it is historical or fabricated. Most of Rome’s legends recounted would have been regarded as historical by the Romans. Any visitor to Rome in the first century BC, asking any inhabitant a related question, would have been pointed to the tree where the basket containing the twins Romulus and Remus washed up, the cave where the she-wolf later nurtured them, and the hut where the boys grew up under the care of their adoptive parents.

Romulus and Remus being cared for by a wolf, the god of the Tiber river sitting on his urn, a woodpecker that brought them food, and a shepherd discovering the infants, by Peter Paul Rubens (1615) Pinacoteca Capitolina in Rome (Public Domain)

Invented Legends of Rome

It is indisputable, however, that many of Rome’s legends were invented or at least partly invented. Romulus, believed to have been the son of Mars, is clearly a mythical figure, though some present-day historians give credence to the deeds attributed to him. The life and deeds of the six kings who succeeded Romulus should also be treated with caution, though it seems likely that a period of kingship preceded the Republic, since an inscription found in the Forum contains the word rex or king, albeit followed by the limiting noun sacrorum in the genitive case, meaning ‘in relation to sacred affairs’.

Some etiological legends may have been invented to explain obscure customs or traditions. An example is Horatius Cocles’ jump from the Sublician Bridge into the River Tiber, which recalls the tradition of throwing straw puppets from the bridge at a festival known as the Argei.

- The Romulus Riddle: Did the Legendary First King of Rome Really Exist?

- The Seven Kings of Rome: Tumultuous Origins of the Roman Republic

- Has Livy’s History of Rome Skewed Our View of the Early Empire?

Other etymological legends may have grown up around a cognomen, a kind of nickname that was given to an individual which became hereditary. For instance, the name Scaevola, ‘Left-handed’, purportedly granted to a young man who sacrificed his right arm in the cause of duty, might originally have been a nickname assigned to a prominent one-armed man, whose descendants created the self-serving story to ennoble their family. Rome’s second king Numa Pompilius might have acquired his reputation for religiosity solely because his name recalls the Latin noun numen, meaning ‘divine power’. Rome’s third king Tullus Hostilius might have been deemed bellicose solely because his name is cognate with the Latin adjective hostilis, meaning ‘warlike’. Still, other legends are exercises in wishful thinking, such as the report of the elderly patricians who calmly awaited the arrival of the Gauls dressed in their ceremonial robes.

Tullus Hostilius defeating the army of Veii and Fidenae, modern fresco. ( Public Domain )

There are places, too, where legends are at variance with archaeology. According to the tradition established in the first century BC, Rome was founded on April, 21, 753 BC to be precise, the day of the festival held in honour of a minor goddess called Pales, protector of shepherds. Archaeology, however, indicates that the future site of Rome was continuously occupied from at least as early as 1400 BC and that the earliest evidence for the existence of an organized centre, - the presence of something resembling a forum which was essential to its civic status - dates to about 650 BC. This in turn raises the question whether Rome was ever ‘founded’ in one go, so to speak. Most ancient foundations are the product of steady growth and it is highly likely that Rome, too, was not built in a day. These problems aside, archaeology confirms that the ancient settlement did in fact expand in the mid-eighth century, in line with the traditional date of Rome’s foundation.