Giants Among Men Who Walked The Earth

Today, overachievers are often called “giants in their field" and “giants among men”- terms which define talent, ability and zeal. However, in the ancient world, the word “giant” applied to the oversized, generally supernatural, larger than life beings of mythology and religion. The Greeks presented the Titans and the Bible has the barbaric Goliath, while modern mythologists have created Gulliver and the Big Friendly Giant (BFG), but between the lines of folklore and supernatural narratives, giants really did walk on earth. Not the giants associated with Smithsonian Institute conspiracies though, but mega-tall individuals and races of people who stood above the average at their respective times in history.

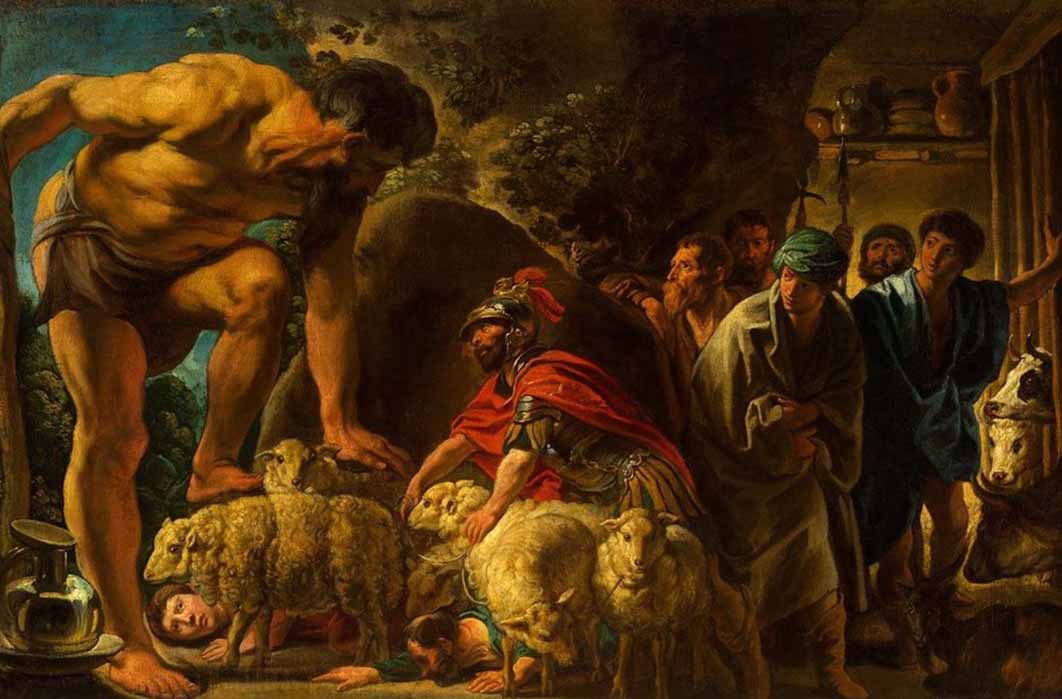

David faces the giant Goliath, lithograph by Osmar Schindler (1888) (Public Domain)

The word “giant” was first coined in 1297 AD, from ‘gigans’, or the “gigantes” of Greek mythology, and currently the word is used to describe larger than average people who suffer ‘gigantism.’ This very rare medical condition happens when a child is exposed to higher levels of growth hormones in their bodies before the fusion of the growth plate which generally occurs soon after puberty. This condition affects about three people in a million, worldwide, and in most cases, the increased growth is a sign of Hyperplasia (abnormal tumors) on the pituitary gland.

The Dreamscape Of Giant Archetypes

Mythologists and folklorists suggest the archetype of the giant is possibly a personification of the human struggle against the destructive forces of Mother Earth, and this is perhaps why cunning giant slayers defeated their foe in battles where ‘brains’ always win over ‘brawn’. Celtic, Norse and Greek mythologies all have early races of giants ruling the world before humans, and the giants of Norse mythology (Jötunn) were primeval beings that existed before being overcome by the gods. Many historians say this violent interaction between the two competing cosmic forces, the Norse gods and the giants, reflects how the Vikings dealt with surrounding cultures, with the Vikings being the gods and everyone else being the slayed giants. When the Normans later translated the Norse word Jötunn - the closest word they had was geant, from the Latin gigans, referring to the Greek/Roman Titans, and the two groups, Norse and Greek, became one creature in fables.

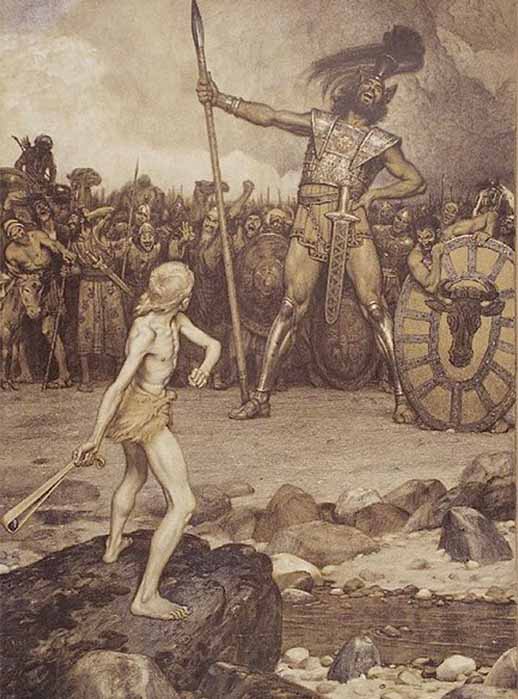

Poseidon (left) holding a trident, with the island Nisyros on his shoulder, battling a giant (probably Polybotes), red-figure cup (c. 500–450 BC) Cabinet des Medailles (Public Domain)

Legends tell of giants living just beyond the furthest mountains in any given environment, and also on remote islands just beyond sight, but for as long as humans have slept, the giant has haunted dreamscapes. According to an article Giants in Dreams psychologist Carl Gustav Jung determined “angry giants can indicate physical fear and personal insecurity and a need to ‘think’ our way beyond their apparent ferocity, or friendly giants, which remind us of our human potential and far-reaching capacity of kindness and warmth.” Therefore, starting out as archetypes of human lives, the giants of story, myth and folklore were literary devices specifically used to draw heroism from humans, and to express the challenges that have to be overcome in life to achieve absolute freedom. This is perhaps why in so many giant stories the creatures were only ever overcome after the unity of a human with divine providence, giving reason to why the Greek giants Aphrodite, Poseidon, Athena and Dionysos all entrusted humans with the final act of slaying their enemy giants.

- Landscape of Scottish Mythological Gods, Goddesses and Giants

- Measuring Up Real World Archaeological Giants

- The Giant of Antrim, Ireland: Biblical Titan or Colossal Hoax?

While stories often interchange the words ‘giant’ and ‘ogre’, the two have very different underlying meanings. According to Marina Warner’s book No Go, the Bogeyman: Scaring, Lulling, and Making Mock the ogre is related to the Oedipal plot. In the original Greek myth, a dark prophecy foretold that Oedipus would murder his father and marry his mother, so he left his home in Corinth to escape this destiny, but the sub-text is power struggles between fathers and sons. Warner also said ogre-stories are about “food and power, about food in the right place and who puts it there, and vice versa.” Grasping the archetypal nature of giants in mythology and dreams, lays the foundation for an understanding of how the real giants of history might have been regarded, revered and feared in their respective communities.