Women Gladiators: Sensational Spectator Sport For Roman Audiences

It may all have started when female sword fighters performed at funerals in the very early days of Rome. There may also be some connection between women participating in chariot racing and women gladiators. The Greek Heraean Games were pivotal: they were a four-yearly female sports event dedicated to Hera and founded by the legendary Queen Hippodameia; they would later become a template for the Olympics and continued for centuries until suppressed by the Christians. Apart from the usual foot races, javelin throwing and so on, the games included female chariot races. According to Pausanias’ Description of Greece Hippodameia assembled a group known as the ‘Sixteen Women’ to organize the Heraean Games, during which the women competitors, incidentally, wore men’s clothes. A first-century AD inscription from Delphi records that two young women competed in races, possibly those at the Sebasta festival in Naples in the Roman Empire and during Emperor Domitian’s reign there were races for women at the Capitoline Games in Rome in 86 AD.

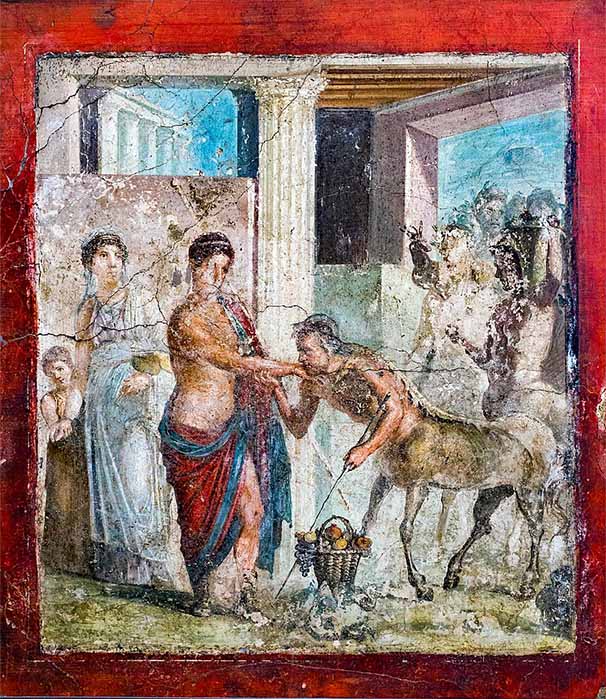

Hippodameia greeted by a seemingly genteel Centaur in a wall painting from Pompeii (ArchaiOptix/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

There is a tendency to think of gladiators only as men, thanks largely to some epic Hollywood films. However, women were not uncommon competitors in the amphitheaters around the Roman world, playing out the phony fights and grappling in close combat, much to the delight and carnal titillation of the audiences: the nearest the modern world has come to it, is probably female wrestling. The women were usually warm-up acts providing light relief in between the top-of-the-bill, crowd-pleasing gruesome and gory acts.

House of the Gladiators Kourion, Cyprus. The central figure (Darios) is positioned as a referee but wears a citizen's high-status toga or tunic with broad stripes (third century AD) (Klaus D. Peter / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Women gladiators might have shared their particular stage, for example, with an elephant walking on a tightrope – as at games arranged by Nero in honor of his mother, Agripinna the Younger, whom he had recently murdered. Roman historian Tacitus expresses outrage by female participation: ‘Many ladies of distinction, however, and senators, disgraced themselves by appearing in the amphitheater’. The fact that these were rich women and had no need of manumission or celebrity suggests that they did it for the adrenalin. The historian Dio tells of another spectacle in which Nero, entertaining King Tiridates I of Armenia, put on a gladiatorial show featuring Ethiopian men, women and children. Petronius describes a woman who fights from a chariot booked for a gladiatorial show at a festival.

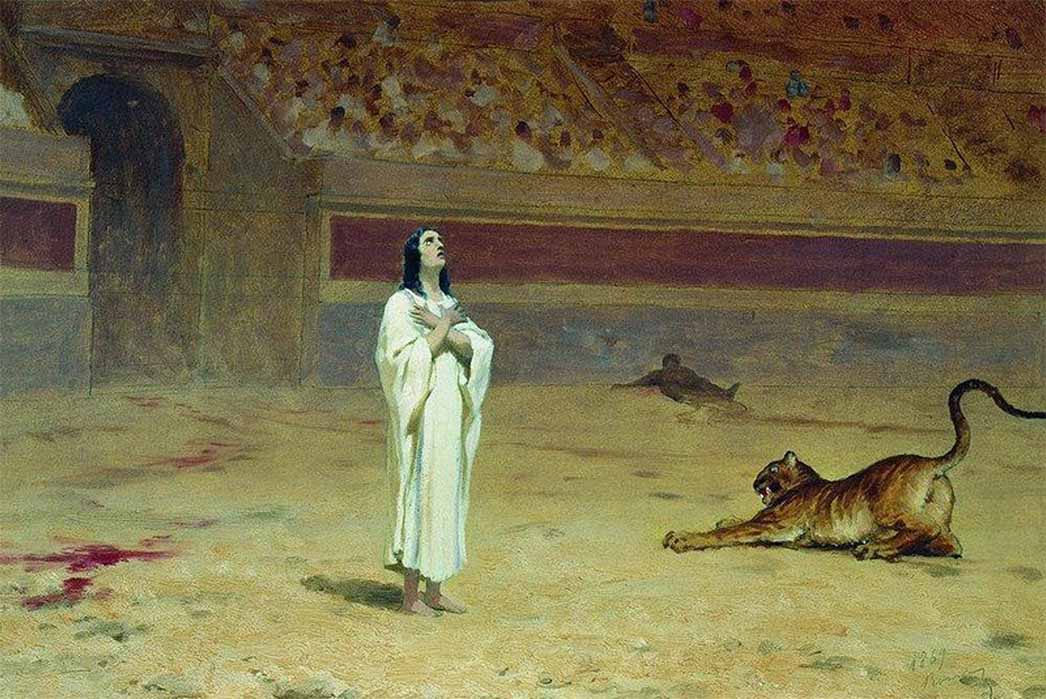

Martyr in the Circus Arena by Fyodor Bronnikov (1869) (Public Domain)

Beasts Sharing Stage with Women in the Arenas

Women gladiators were just one of many variations on a theme put into the arena to keep the baying crowds entertained. In the hundred-day games staged by Emperor Titus, women competed in a battle between cranes and one between four elephants – just a handful of the 9,000 beasts slaughtered in one single day, ‘and women took part in dispatching them.’ They must surely have participated in Trajan’s games in 108 AD which lasted 123 days and in which ‘eleven thousand or so animals both wild and tame were killed and ten thousand gladiators fought’. Martial, in his De Spectaculis, describes women battling in the arena, one dressed as Venus. Another, as a venatrix, animal hunter, subdues a lion: ‘Caesar, we now have seen such things done by women’s courage’, he marvels. Statius describes in his Silvae ‘the sex untrained in weapons recklessly dares men’s fights! You would think a band of Amazons was battling by the River Tanais’.