The Language And Symbolism Embedded In Medieval Stone Bibles

In the Middle Ages, paintings and sculptures had a powerful educational function. The Church relied on the language of images to influence the illiterate masses. Popular education was nourished not only through the organ of hearing, with sermons, litanies and collective prayers, but also through the organ of sight. The illiterate masses were guided to recognize models to inspire the conduct of their lives by visually retracing the events in the lives of Jesus, the saints, the martyrs, the hermits, painted and sculpted in religious buildings. Medieval imagination was nourished by the sources of the sacred through instructive figures. Medieval art certainly did not only appeal to the humble, but proved to be a precious vehicle for teaching the truths of the faith to those who could not access written texts.

Exultet Scroll at Opera del Duomo di Pisa Museum(Federigo Federighi/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

In 1025, the Synod of Arras decreed that what the illiterate could not understand through writing should be taught through painting. Throughout the Middle Ages, the most commonly used technique was tempera, using pigments bound with egg yolks and water. The Exultet, scrolls made of strips of parchment sewn together, used during the Easter liturgy, are among the most interesting testimonies of Medieval art. These manuscripts, which were unrolled from the pulpit in the presence of the faithful, have the peculiarity of having the text and images placed in the opposite direction, that is the written part facing the reader, while the images face the observers. In this way, while a deacon recited the text, the faithful could see the images illustrating the words.

Romanesque and Gothic Differences Of Light And Color

Regarding architecture, it should be noted that the decorations are much more present and evident in Gothic churches than in Romanesque ones. Romanesque structures present more robust and heavy forms and a sober style prevails, where one can recognize a clear inspiration from Roman and early Christian art. The lighting is poor and the artistic language, being mainly addressed to the people, is made up of simple images. The contrast between light and shadow refers to the struggle between the splendor of God's grace and the darkness of sin. The structure of the churches invites recollection and intimate conversation with God. Sculpture is generally used to decorate capitals, pulpits and especially entrance portals, marking the passage from the earthly to the divine world. It should also be remembered that churches were the center of urban life and were not only used for prayer and liturgical functions, but also for public assemblies and commercial negotiations.

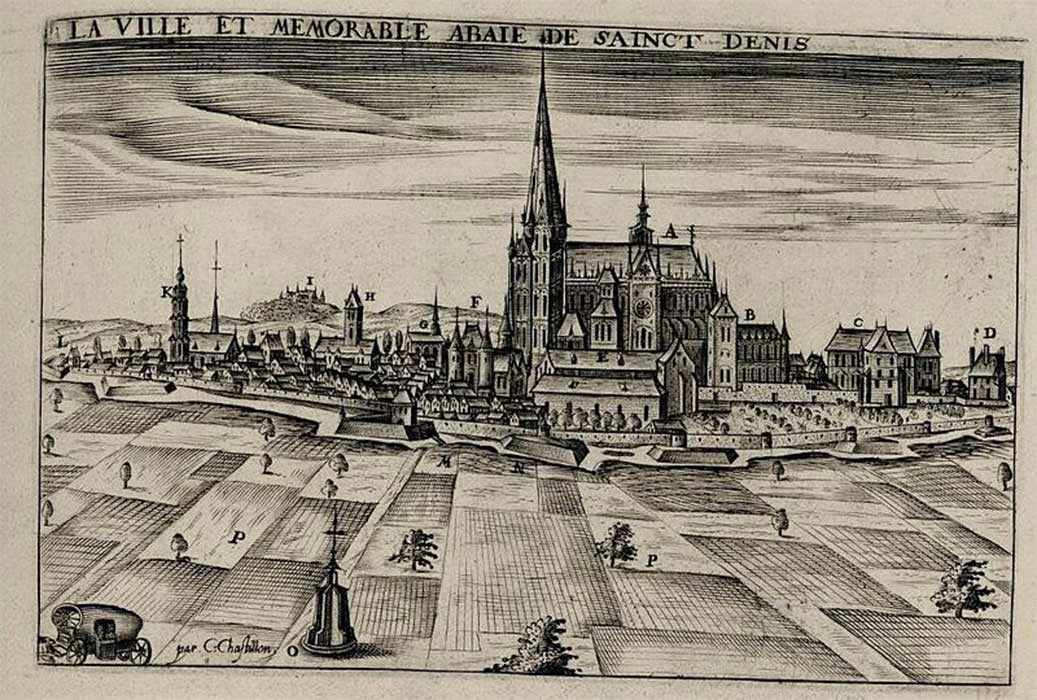

St Denis Basilica by Claude Chastillon (1655) Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art (Public Domain)

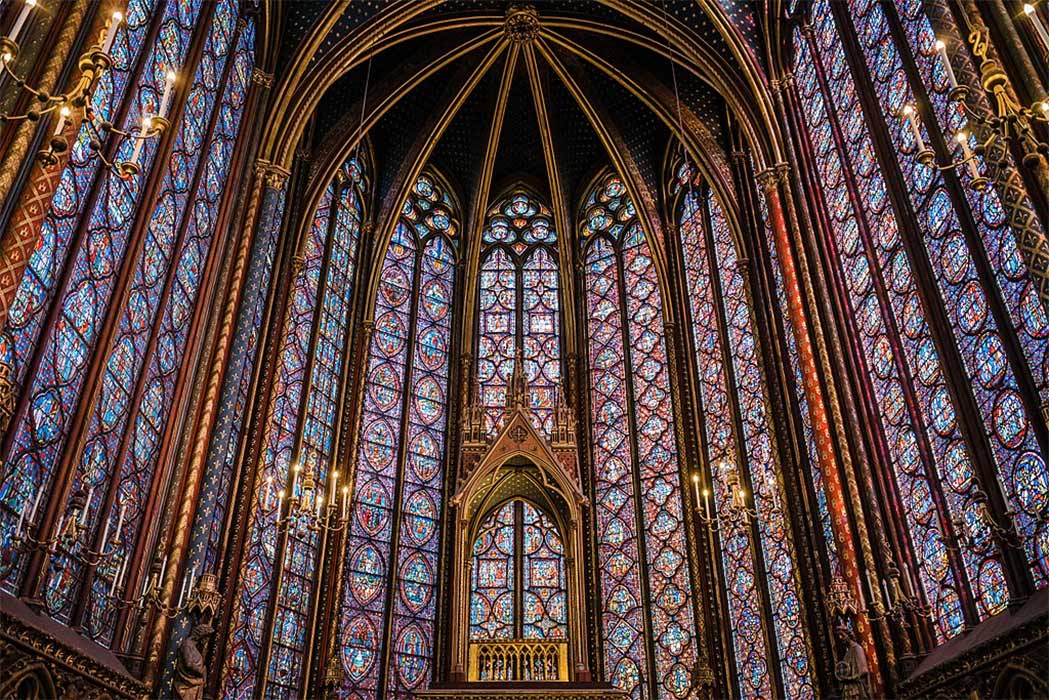

The Gothic style originated in the 12th century in Saint-Denis, France, and from there spread throughout Europe. Every architectural component of the Gothic church suggests an upward thrust and vertical development, in response to the desire to come symbolically close to the Creator. The enormous spaces highlight the fragility of the human being compared to the power of God. Gothic is expressed differently in European countries. In Italy, for example, it is more severe and composed, less grandiose compared to French churches. Great value is attached to light and color. Stained glass windows allow a great deal of light to pass through them, a symbol of the Divine as opposed to darkness, which is a symbol of sin. They consist of small sheets of colored glass, joined together with lead, and the dark profiles of the lead make the colors brighter by contrast. Like the miniature, painting and sculpture, stained glass also has a didactic function.

Sainte Chapelle’s Stained Glass Windows (Oldmanisold / CC BY-SA 4.0)