Striking at the Heart of Pharaoh: Social Injustice and Deception in the Place of Truth – Part I

A couple of years before he celebrated his jubilee, Ramesses III was beset by internal problems. A great king who had combated vicious enemies from all corners and was deified by his subjects for his decisiveness; he was cast into a cauldron of unpopularity for a brief while, when a seemingly innocuous protest about delayed wages by elite artisans from Deir el-Medina turned into a commentary on corruption and social injustice which led to the world’s first recorded strike.

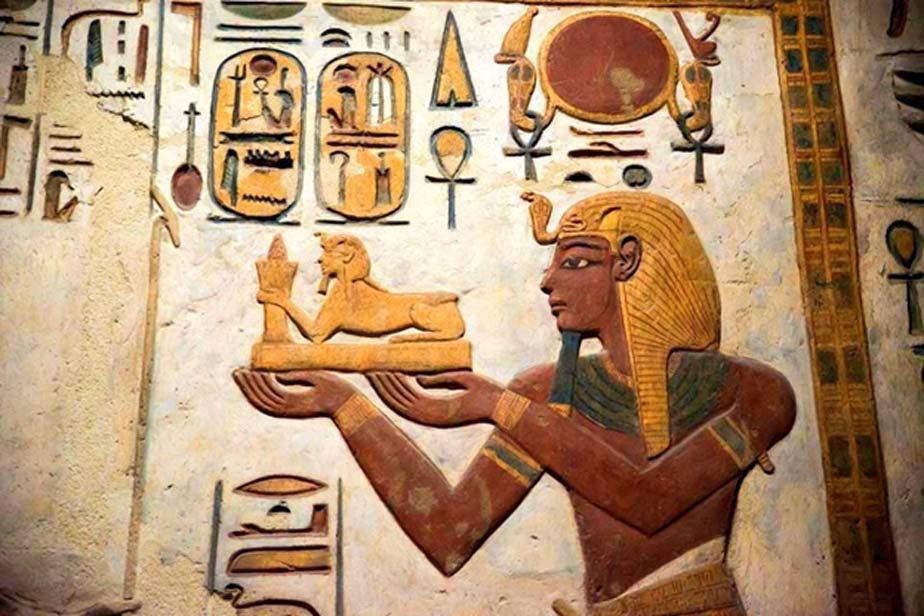

At a time when several civilizations in the region were biting the dust one after another, the astute leadership of Ramesses III ensured a stupendous militaristic victory over Egypt’s enemies, notably the Sea Peoples. In this exquisitely painted relief the king is shown making offerings to the gods in the sanctuary of the Temple of Khonsu at Karnak. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

A King Like None Other

Over the course of two decades on the throne, Pharaoh Ramesses III had achieved military victories that would have been the envy of even his formidable predecessors. When every kingdom in the Near East and Mediterranean was decimated by the treacherous reign of terror unleashed by a coalition of forces known as the Sea Peoples, under the powerful leadership of Ramesses III the Egyptians alone had successfully repelled the attack on their soil. Not just the Sea Peoples, but the Libyans and a rag-tag assemblage of tribes too tasted the wrath of the pharaoh during this period.

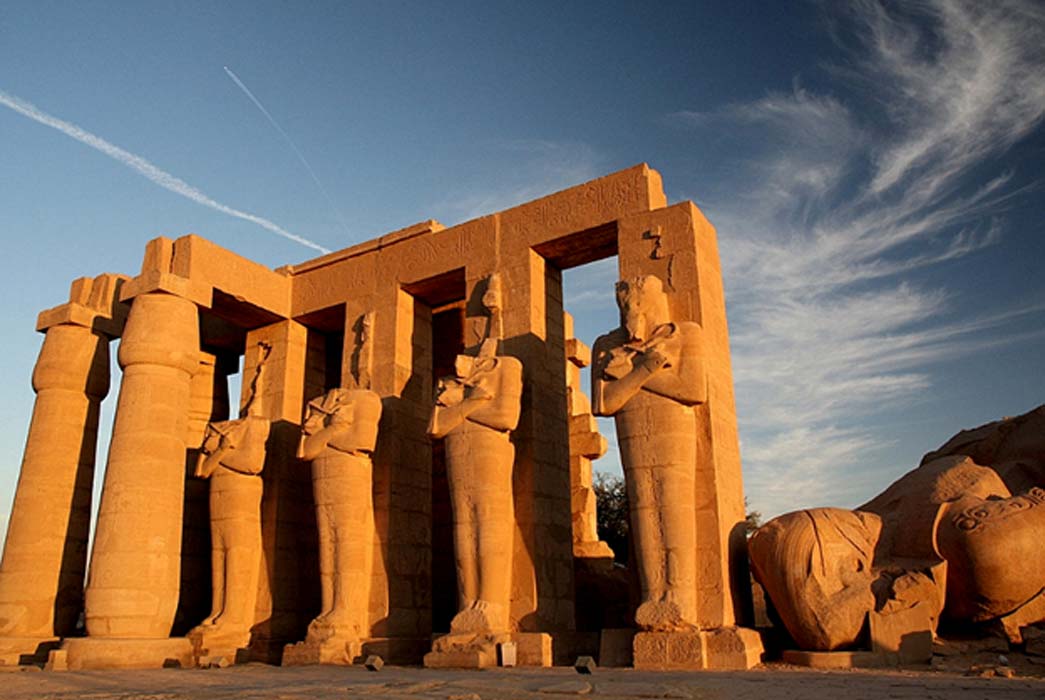

In what was an unwritten law in ancient Egypt, monarchs celebrated their triumph in battle by erecting grandiose monuments in honor of the gods. These war memorials, that were filled from top to bottom with inscriptions and depictions of battle scenes showing the pharaoh’s gallantry – much like a bulletin board – also doubled up as effective propaganda machines. It was now the turn of Ramesses III to follow suit and commemorate his improbable military victories. But instead of embarking on commissioning a new monument, Ramesses III converted his pre-existing ‘Mansion of Millions of Years’, which was a palace-cum-mortuary temple modeled on the lines of the Ramesseum built by his outstanding predecessor Ramesses the Great. On the entire northern wall of this temple a vast tableau depicting the land and sea battles against the Sea Peoples was carved for all the world to see. “So Egypt’s last great royal monument commemorated the country’s last great military victory,” writes Toby Wilkinson.

The imposing Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu. The pharaoh used this structure as his royal palace and later converted it into a war memorial in order to commemorate his victory over the Sea Peoples and the Libyans. This image was shot during an aerial survey of the West Bank in 2010.

Following a decade of unending campaigns against the Sea Peoples, the Libyans and their tribal coalition – all of whom he routed thoroughly securing Egypt’s borders – Ramesses III finally sought to turn his attention to important matters such as fulfilling vital duties of office and deifying the gods through rites and rituals. The completion of the exceptional monument at Medinet Habu invigorated the king so much that in 1172 BC he decreed temple inspections throughout the length and breadth of the country; particularly at Karnak (Ipetsut), the most sacred religious complex in the entire land, where he commissioned a new way station and a temple to the moon god Khonsu.

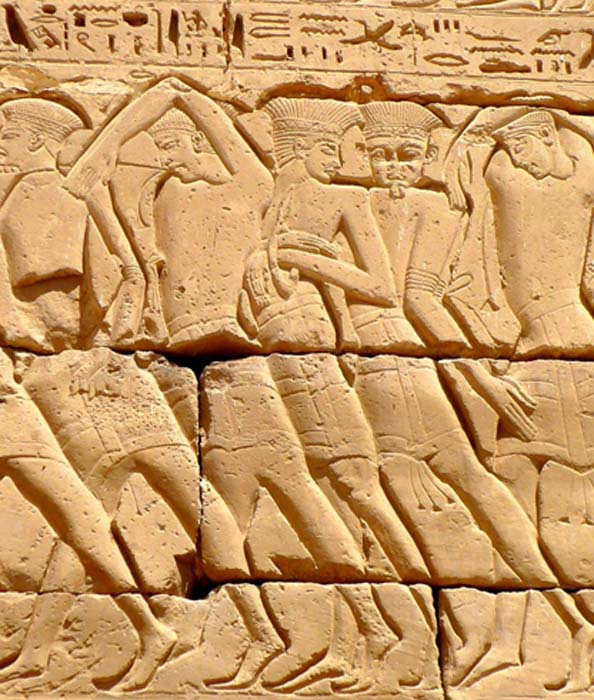

Bound Philistine prisoners of the confederation that comprised the Sea Peoples being paraded after their capture. Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III. Medinet Habu. (CC BY-SA 3.0)