The Ancient Origins Of Modern Greece

Nationhood is a figment of the collective imagination, actualized by a cluster of symbols and ideas – flags, anthems, sports teams, traditional dress (sometimes), a common religion (often), shared values (whether or not they are upheld) – which help to build a sense of collective identity. Of course, a nation state is a geographical entity as well, though it is perfectly possible to be a nation without actually owning any territory. The ancient Hebrews in their years of wandering considered themselves to be what today would be called a nation, long before they acquired a homeland. But in essence the nation state is a relatively recent idea, which came to fruition in the 19th century.

The Byzantine castle of Angelokastro successfully repulsed the Ottomans during the first great siege of Corfu in 1537, the siege of 1571, and the second great siege of Corfu in 1716, causing them to abandon their plans to conquer Corfu (Dr.K. / CC BY-SA 3.0)

This is certainly true of the Greek nation state, which arrived on the world stage as the result of the War of Independence that the inhabitants of the Greek mainland and the Aegean Islands waged against the Ottoman Turks. The Ottoman Turks had been in power in the region since 1457 and Greece as an independent country only came into being in 1830, when, as a result of what was called the London Protocol, the Great Powers, notably Britain, France, and Russia, having fought alongside the Greeks, magnanimously (in their eyes, no doubt) bestowed nationhood on the fledgling entity that emerged victorious from the war. It was an entity that was very much the creation of those Great Powers – a romanticized Greece indissolubly bound to its Classical past.

First Hellênes of Hellas?

So, when did the ancestors of the people who call themselves Hellênes, citizens of the country called Hellas, first appear? The question can only be answered very approximately. The earliest evidence for humans living in Greece goes back to the Lower Palaeolithic era, when elephants, rhinoceroses, mammoths and lions roamed freely through the land mass known as Eurasia. In 2015, a team of archaeologists excavating at Marathousa near Megalopoli in the Peloponnese, currently the earliest known archaeological site in Greece, unearthed a location where elephant butchery took place some 50,000 years ago. The identity of those engaged in this activity is, however, impossible to determine. It is unknown whether they even belonged to homo sapiens, or whether they were Neanderthals.

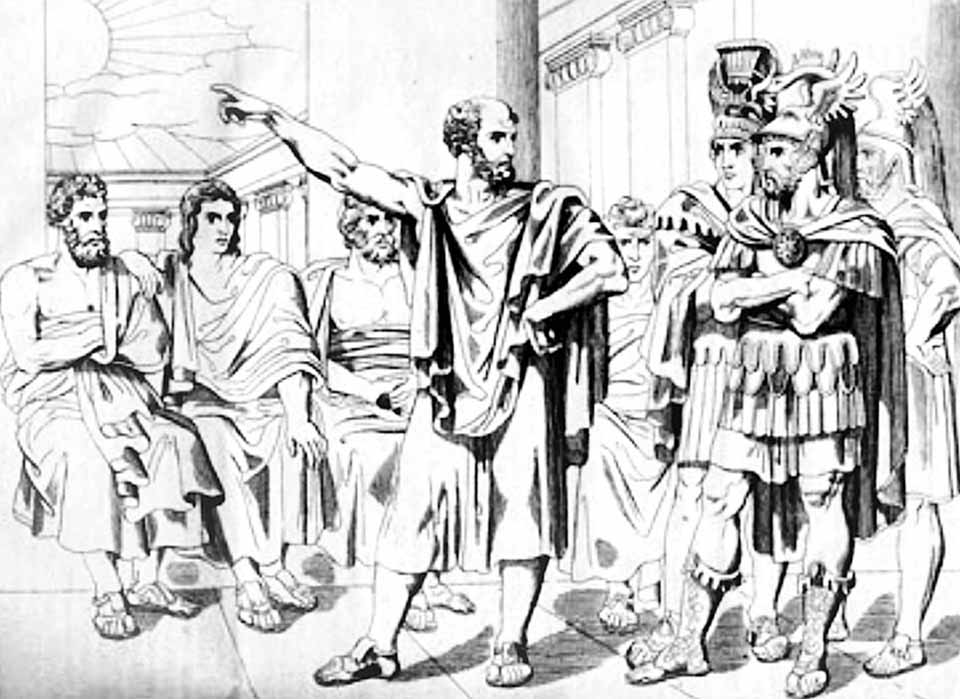

Answer of Aristides to the ambassadors of Mardonius: "As long as the sun holds to its present course, we shall never come to terms with Xerxes" by M. A. Barth - 'Vorzeit und Gegenwart", Augsbourg, 1832 (Public Domain)

Which raises another fundamental question: what does having a common identity, or to phrase it differently, seeing oneself as the member of a single racial group, actually amount to? To answer that question, it will be useful to consult the Greek historian Herodotus, who reports that shortly before the Battle of Plataea, which resulted in the defeat of the Persians and their retreat from mainland Greece following the unsuccessful invasion led by King Xerxes in 479 BC, the Spartans entreated the Athenians not to abandon the Greek cause. In response, the Athenians assured their allies they would never come to an agreement with the Persians “so long as the sun travels on the same course as it goes on now” – an impressive oath – adding that they were united to the Greek cause “by the same blood, the same language, the same sanctuaries, the same religious practices, and the same way of life.” Very likely, lots of people today would consider this to be a pretty good outline of what constitutes a national identity, even though it is not particularly precise. What, for instance, does it mean to have the same blood? Intermarriage has been a feature of the earliest human societies – it is estimated that the DNA of homo sapiens has been diluted by between four to six percent Neanderthal DNA – and there is no reason to suppose that the ancient Greeks, or any other ancient people for that matter, were racially ‘pure’, though of course they had abiding ties to their community.

It's All Greek

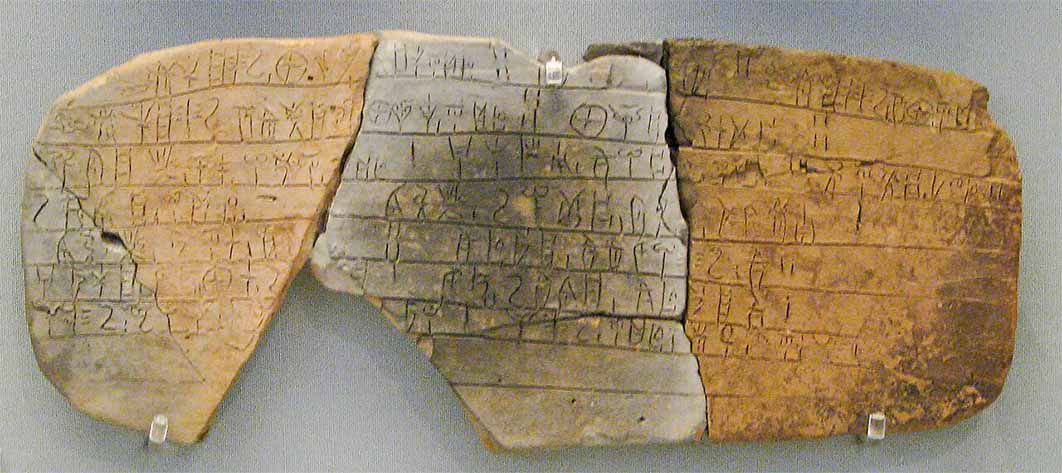

Perhaps it is better, then, to try to trace the origins of Greek identity through language. The earliest Greek writing which archaeologists have been able to decipher is known as Linear B, a cuneiform or wedge-shaped script used by the Bronze Age Mycenaeans, which is attested mainly on clay tablets dating from about 1400 BC. Clay tablets inscribed with Linear B have been found at Mycenae and Pylos on the mainland, and at Knossos on Crete. Linear B is undisputedly Greek. Significantly, the tablets also refer to a number of gods who were being worshipped by the Greeks centuries later, including Diwios (Zeus), Era (Hera), Diwonusu (Dionysus), and Posadone (Poseidon).