Hermetic Individuation: The Discovery of the Self in the Teachings of Hermes Trismegistus

At the core of the philosophy of Plato, we find one of the oldest written accounts of a type of psychological physics in the history of Western literature. Drawing from Pythagorean and archaic Greek cosmological concepts, Plato developed his theory of the archetypal forms or ideas. The archetypal forms are primary: the objects and phenomena of sensible reality are derived from them. As the timeless forces that shape the physical world, they represent a hidden, greater reality and are thus of a more substantial and pure being than the realm of physical manifestation. The archetypal forms are part of the intelligible world, a transcendent realm above or beyond the physical world and from which sensible reality draws its very existence. Overseeing the process by which all things are brought into existence from the archetypal forms is a deity known as the demiurge or craftsman, whose work is to oversee the process of becoming by which reality itself comes into existence.

Plato in his academy, drawing after a painting by Swedish painter Carl Johan Wahlbom (Public Domain)

The archetypal forms were associated with the mathematical principles of Pythagoras on one hand and the gods and mythic beings of archaic times on the other. In this sense they were considered to represent the experiences of human beings. Athena became associated with mind, for example, while Apollo became representative of Illumination. However we may choose to view this aspect of the archetypal forms today, the fact is that Platonic philosophy represented a major step forward from primitive superstition and archaic religion, as Greek man attempted to redefine his experience of the numinous and comprehend universal experiences, emotions, and concepts in a new light. Associated with this type of experiential knowledge were altered states of consciousness, which in the Platonic dialogues are referred to as divine manias. Mania was believed to have inspired religious experiences, the great poets, and oracles, such as the oracle of Delphi.

Between roughly 200 BC and 200 AD, the spread of Greek language and philosophy around the world of Late Antiquity resulted in an era of syncretism, as various theologians, poets, and other thinkers merged Platonic philosophy with their own religious and philosophical traditions. This is the era of Middle Platonism, when such figures as Plutarch of Chaeroneia (46—120 AD) and Philo of Alexandria (20 BC—50 AD) composed their works. As an example of the hybrid, free thinking nature of the Middle Platonic period, Philo—who was a Hellenistic Jew—combined Platonic philosophy with his allegorical interpretations of the Hebrew scriptures, articulating an elaborate cosmology out of what is today called the Old Testament. In fact, many scholars consider Philo’s interpretation of the Logos (Word) as a divine creative principle of the Hebrew God to have been the source of inspiration of the later Christian doctrine of the presence of the pre-incarnate Christ in the Old Testament scriptures. The Logos—as explained in the opening of the Gospel of John—was made flesh in the historical Jesus.

Hermes Trismegistus, floor mosaic in the Cathedral of Siena (Public Domain)

Hermetica

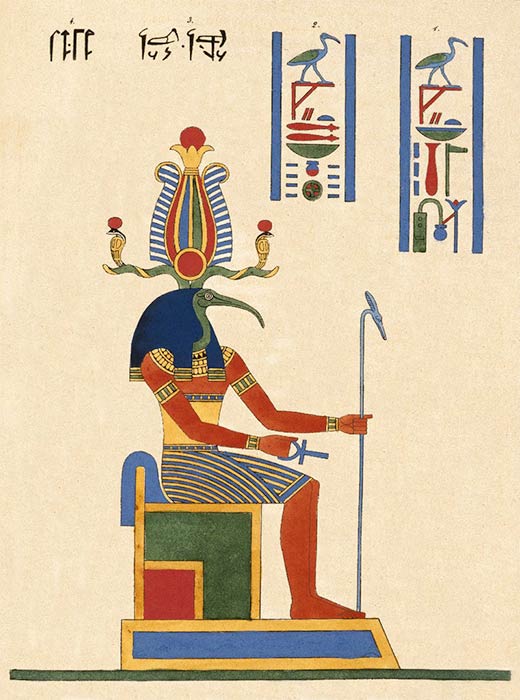

During the first few centuries AD, in Roman Egypt, a group of temple priests followed in the Middle Platonic tradition of hybridizing Greek philosophy with local religious tradition and invented what has come to be known as the Hermetic philosophy (Bull 2018; Fowden 1993). However, it should be emphasized that Hermeticism is less an actualized philosophical system than a path or “way” of personal revelation, which unfolds in the contexts of a worldview made up of elements of Platonic cosmology synchronized with aspects of Egyptian and Hebrew theology. The hybrid nature of the Hermetic “way” is represented in the mythic founder to whom the Hermeticists attributed their wisdom: Hermes Trismegistus (“thrice great” Hermes). Hermes Thrice Great never literally existed, and represents the combined figure of the Greek Hermes—messenger of the gods—and the Egyptian Thoth, who served as scribe of the gods and was considered the patron of writing, mathematics, and sacred wisdom.

The Egyptian god Thoth, the second Hermes. Brooklyn Museum (Public Domain)