Herodotus, Cato the Censor and Josephus: Understanding the Life and Times of Historians of the Ancient World

For thousands of years, we turned to history to explain the what, why and how an event happened. Although “historian” did not become a professional occupation until the late nineteenth century, the purpose of the investigation and analysis of history generally remains the same for ancient as well as for modern historians, which is to study the past in the hope that the knowledge can, in some way, assist us in the present and future.

However, the reality of life as a historian is that despite our best efforts, there will always be disagreements between one historian’s version of events with another. We are continually reminded that one’s perception of history, and indeed of life, is greatly influenced by one’s viewpoints, backgrounds and environment. This reality is also apparent for ancient historians. In fact, histories of their own lives are almost as intriguing as the events of which they have written. Herodotus had to struggle to break out of the tradition ingrained in his culture, Cato’s vocalized hatred towards Carthage led to its eventual destruction, and Josephus was branded as a traitor even long after his death. All these began as personal events which lent themselves to writings that are still studied, translated and analyzed to this day.

Herodotus: The Struggle between History and Storytelling

The Histories by Herodotus is the earliest Greek prose to have survived intact. Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c. 484–c. 425 BC), dubbed by many as the “Father of History”, was the first historian known to have broken from Homeric tradition of poetic storytelling and collected his materials critically to arrange them into a coherent narrative. The Histories is a record of Herodotus’ investigation on the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars which also includes a wealth of geographical and ethnographical information.

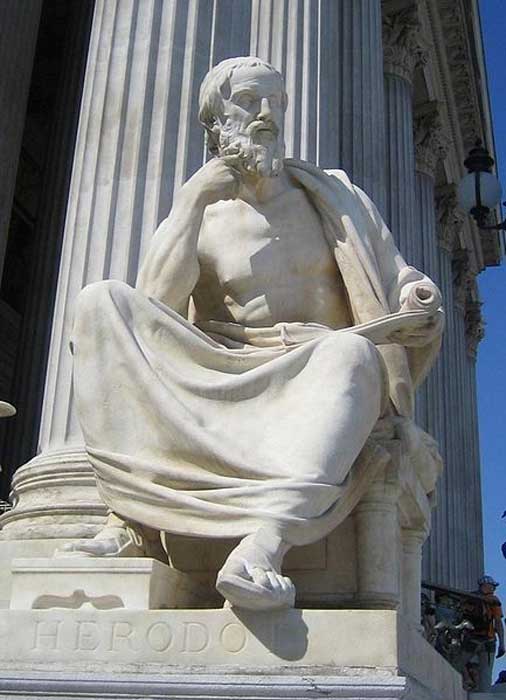

Statue of Herodotus (Wienwiki / Walter Maderbacher/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Herodotus was born in an influential Persian family and it was possible that he would have heard local eye-witness accounts of, and had even seen for himself, many important events within the empire. Halicarnassus, in Herodotus’ life time, had ended its close relations with its Dorian neighbors and had helped pioneer Greek trade with Egypt. The city was, therefore, an international port within the Persian Empire, and Herodotus’ family could well have had contacts in countries under Persian rule, facilitating his travels and his researches, thus enabling many of his first-hand accounts. His eye-witness accounts indicate that he traveled in Egypt in association with Athenians after an Athenian fleet had assisted the uprising against Persian rule in 460–454 BC.

The theater of ancient Halicarnassus, built in the 4th century BC during the reign of King Mausolos and enlarged in the 2nd century AD, the original capacity of the theatre was 10,000. Bodrum, Turkey. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Herodotus occupies a peculiar position as the first historian to emerge from a tradition that relied on story-telling by way of gaining knowledge and education. It was therefore to be expected that he would have drawn on an Ionian tradition of story-telling, collecting and interpreting the oral histories he heard in his travels. These oral histories often contained folk-tale motifs, however, they also incorporated substantial facts relating to geography, anthropology and history, all compiled by Herodotus in a new style and format.

- Thucydides: General, Historian, and the Father of Scientific History

- The Rape of Lucretia: A History of the Ancient Wife Who Changed the Destiny of Rome

- Professor reveals evidence that Athenian epidemic of 430 BC was first recorded Ebola outbreak

However, the story-tellers’ influence in his work is undeniable. His writing still includes rather fantastical accounts, earning him the nickname “Father of Lies” by critics in early modern times. However, a deeper similarity remains. Herodotus writes with the purpose of trying to explain the causes of events. This traces itself back to Homer himself who opened the Iliad with the question, “which of the immortals set these two at each other's throats?” As Homer before him, Herodotus’ means of explanation does not always point to a simple cause. As he worked from many different sources, his explanations also cover a number of potential causes and emotions. As he took many of his sources from Homeric writings (which were common in his day than the much more modern concept of peer-reviewed historical papers which had not yet existed in his time), it is understandable that he would have taken some of the writings from his sources as facts.