The Hunt for Herihor: Waning Pharaonic Power and Advent of Priest-kings–Part I

Early in the Twenty-First Dynasty, a High Priest of Amun-Re, Herihor, declared himself ruler. The custodians of the cult of the state god finally got what they had always yearned for—overtly and covertly —absolute power. Weakened by political and religious machinations, famine, anarchy and greed; hard-won Egyptian glory began to wane slowly, but with inexorable certainty.

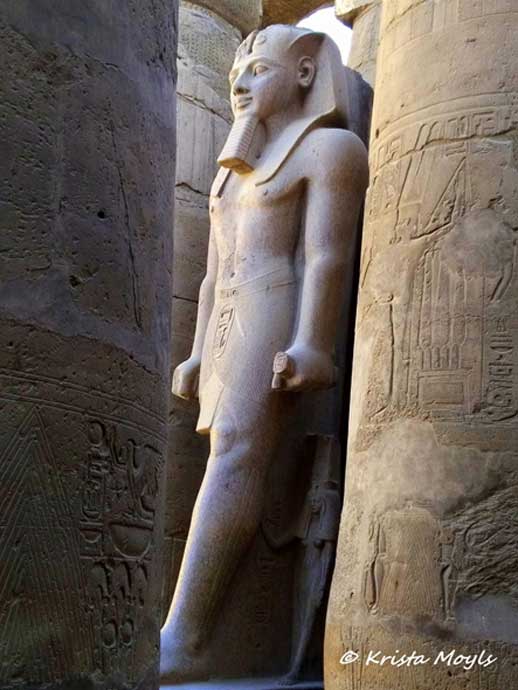

The grandiose and wealthy Karnak temple, dedicated to the Theban triad of Amun, Mut and Khonsu, is the largest religious building ever made. Covering about 200 acres (1.5 km by 0.8 km), it was a place of pilgrimage for nearly 2000 years. Here, an imposing sculpture of Ramesses II stands proud in the precincts of the temple.

Two Kings, One Land

During the New Kingdom, Egypt’s temples grew fabulously wealthy, thanks to a significant portion of the war booty and taxes – among other sources of revenue – that were donated particularly to the treasury of the state god Amun. Regular tributes of precious metals, livestock and slaves from subjugated realms made the temples powerful; and the high priest at Karnak rivaled the king’s prestige. By the time of Nebmaatre Amenhotep III, Amun-Re’s priests had become a state within a state and were perhaps within range of imperiling the supremacy and sanctity of the crown.

“Some have proposed that Akhenaten's religious revolution was a backlash against the powerful and allegedly corrupt priesthood of the god Amun, who controlled tremendous economic resources and supposedly infringed on the authority of the pharaoh. While the temple estate of the god Amun possessed land and personnel far beyond Thebes, the New Kingdom clergy of Amun was dependent on the beneficence of the pharaoh—the priesthood of Amun was powerful because of, not in spite of, the authority of the pharaoh,” John Darnell and Colleen Manassa posit.

Head of a broken statuette depicts Akhenaten wearing the khepresh or Blue Crown (also called the War Crown). This king seems to have attempted to flee the influence of the Amun priests when he shifted the capital to Akhetaten, a new city he had built. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Around 1070 BC, the death of King Menmaatre Ramesses XI – the tenth and last ruler of the Twentieth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt – signaled the end of the New Kingdom Period; whose illustrious rulers had successfully created an empire. The ensuing collapse of pharaonic rule ushered in a time of confusion and chaos in the land referred to by scholars as the Third Intermediate Period. But the rot had set in much earlier, even during the reign of Ramesses XI, when the failing economy and civil unrest propelled ambitious Theban priests to inch ever closer to the throne. Two monarchs ruling the land was unthinkable and went against the order of Ma’at, and yet, this is exactly what occurred in the aftermath of the death knell being sounded for the Ramessides.

“The administrative division of Egypt into two halves had been a feature of pharaonic government from earliest times, but always with a single king to bind “the Two Lands” together. Once Ramesses XI was dead and gone, his Libyan successors saw no need to maintain this tradition. For them, having two kings ruling concurrently over different parts of the country was not anathema but entirely normal, not anarchy but sensible decentralization,” explains Toby Wilkinson. It is interesting to note how all of this unfolded.