Living Close To The Bone – A Day In The Life Of A Hunter-Gatherer

At the beginning of Herodotus’ Histories, the Athenian lawgiver Solon, one of the seven sages of ancient Greece, points out to his interlocutor Croesus, King of Lydia, that if a person lives to be 70, they will experience 26,250 days – by his reckoning the length of a year is 375 days – and that not any two days will be alike. Solon’s observation is worth bearing in mind when trying to imagine the life of an average hunter-gatherer because the chances are that each day was very similar both to the one preceding and to the one following. To be sure, the constant threat of being eaten by a predator would have alleviated any boredom hunter-gatherers might have experienced, while they also had to be alert to changes in the weather, since an ice storm, say, or a fog could cause havoc. But most days would have been dominated by the endless search for food.

This is the period when hominins – that is to say, all the extinct human species who preceded and including the current homo sapiens– first separated off from gorillas, orangutans, and chimps, perhaps five million years ago. From then until around 8000 BC hunter-gathering was the dominant lifestyle for all hominins. After that date, homo sapiens, the lone surviving species, gradually began to adapt to a sedentary lifestyle by establishing communities and ceasing to lead a nomadic existence.

Hunter-gatherers harnessing fire (Gorodenkoff / Adobe Stock)

Learning to Harness Fire

History by definition is never static and even in the Palaeolithic era big changes were taking place, even though they tended to occur at a glacial pace, no pun intended. The most important development over the past one million years of humans’ history has been the harnessing of fire, a point fully realized by the Greeks, who explained fire as the gift of the Titan Prometheus. Hailed as the friend of man, Prometheus stole fire from Mount Olympus, the abode of the gods, and hid it in a fennel stalk.

It was around 800,000 BC that homo erectus, upright man, a hominin species originating in Africa which became extinct shortly before homo sapiens stepped onto the stage, began using fire to cook food and keep warm. How did they do this? Certainly not by learning how to rub two sticks together. Very likely they took advantage of a fire caused by a lightning strike, which they managed to preserve by feeding it with twigs and branches. Not unrelatedly, both the Greeks and the Romans regarded fire as sacred, presided over and safeguarded by the goddess Hestia (Greek) and Vesta (Roman). Both peoples kept the hearths in their homes permanently alight. Greek settlers heading off to establish a colony scrupulously carried fire from the civic hearth of their mother city to the new foundation to symbolize the deep connection between the two and, one suspects, because of the difficulty in creating fire from scratch, so to speak. The Romans believed that if the fire that burned in the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum died out, catastrophic consequences would shortly follow. Very likely these traditions and fears went back a very long way, even perhaps to the period when homo erectus first harnessed fire.

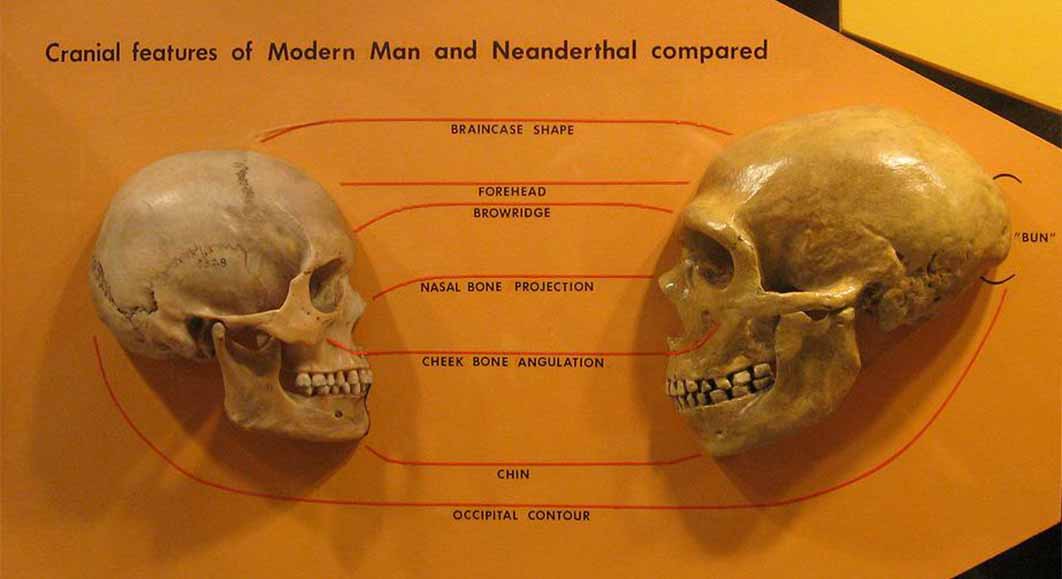

Comparison of Neanderthal and Modern human skulls from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Getting Inside a Hunter-Gatherer’s Head

What went on inside the heads of hunter-gatherers? One can only speculate because there is no way of knowing whether they were equipped with the full range of emotional responses that modern humans possess. Obviously, they felt anger and fear, but what about affection and love? Did they experience regret, remorse, guilt, shame or embarrassment? Did they have an imagination? Could they experience hope or optimism? These states of mind require humans to exist outside the present by reflecting on the past and anticipating the future, but given the routine nature of their lives, it would seem that they had limited ability to do either.

- Study Shows Neanderthals Had Capacity To Produce And Understand Speech

- Neanderthal Child Development Was Faster than Humans, Study Reveals

- New Studies Clash with Previous Analyses On the Life and Fate of Neanderthals

That said, a dramatic change in the anatomical makeup of homo sapiens seems to have taken place some time between 70,000 to 30,000 BC, which among other important consequences permitted the development of modern languages. This event is often called the Cognitive Revolution. It is when commerce and religion began. It is also when homo sapiens began to overrun the earth and drive every other human species, including the Neanderthals, to extinction. Some scholars hypothesize that this was due to an alteration in the structure of the brain. Others maintain that it was brought about by a modification in the voice box, notably by a change in the position of the larynx, which enabled humans to produce a much more diverse range of sounds.