The Hillforts Of Iberia: Ruins Of Proto-Celtic Tribes Who Resisted The Romans

Dotted like an ancient matrix in western Iberia are hillforts that once belonged to the ancient Celtic peoples of Iberia. Some of these forts were dismantled, others left untouched, but they were all abandoned by those who built them. When circumstances during the brutal oppression and ethnic cleansing by the Roman armies made it impossible for the lifestyle which was celebrated by the people who constructed them to continue, they were left standing or destroyed depending on the particular negotiations between the conquered and conqueror or, sometimes, simply on the mood swing of the Roman generals involved. Despite resistance from valiant leaders like Viriathus (died 139 BC) who fought the Romans during the Lusitanian Wars, the region was conquered and the hillforts fell into ruin.

Four well-known hillforts today, clockwise from top left: Escarigo; Argemela; Saint Martinho and Saint Roque (Images: Courtesy Tom Hamilton)

The hillforts were distinct from the more complex proto-urban centers, like the walled Oppida, and exclude the larger fortifications of the Meseta (the large plateau which extends over 81000 square miles in the Iberian interior, now including Madrid as its capital). Each hillfort (castro in Portuguese) controlled a small territory and its surrounding resources: houses, agricultural plots of land, water, roads and mines. The hillforts had a de facto control over the territory in such a way that the Romans, in order to dominate the region, had to destroy them.

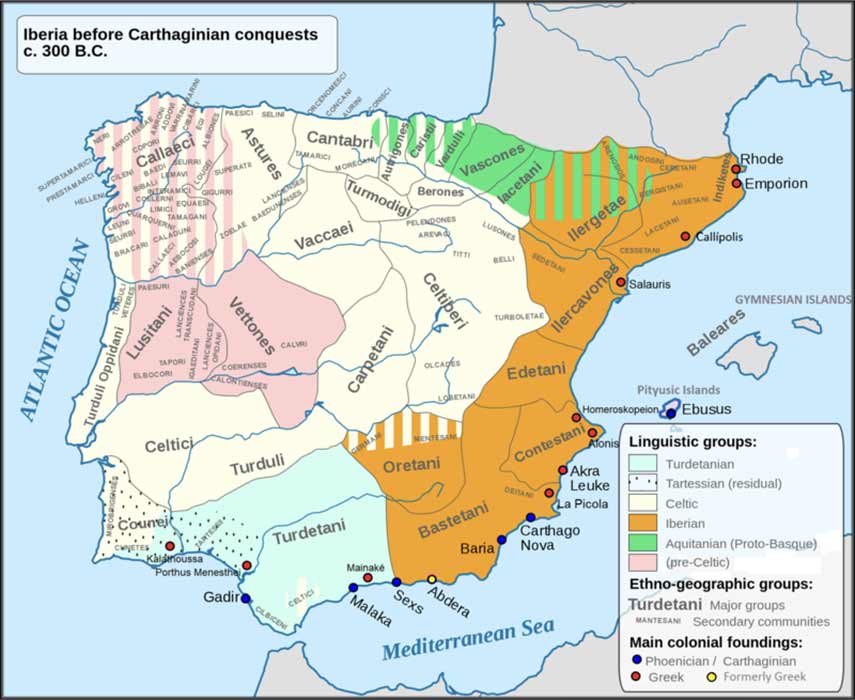

In Iberia, hillforts were constructed mainly in the central Meseta, western and northern regions. This is referred to as the Celtic part of Iberia, to differentiate it from the Tartessic in the south and the Iberians in the east. However, there is some uncertainty with regard to what is called Tartessian, who some claim to be Celtic as well.

Main language areas, people and tribes in the Iberian Peninsula (c. 300 BC) (CanBea87 /CC BY-SA 4.0)

A Melting Pot Of Ethnic Clans

‘Clan’ is a word associated with Scotland. The very word clan has survived because Scotland remained unromanized. Scotland and Ireland preserved what previously had been a western Atlantic reality of a Celtic homeland where only natural, geographical features were frontiers. In Portuguese the word ‘clan’ means families sharing a common ancestry. Strabo, the geographer of the ancient world, said there were too many Iberian tribes (clans) to count, the names were too complicated and, he said his readers would not in the slightest bit be interested in their bizarre names anyway.

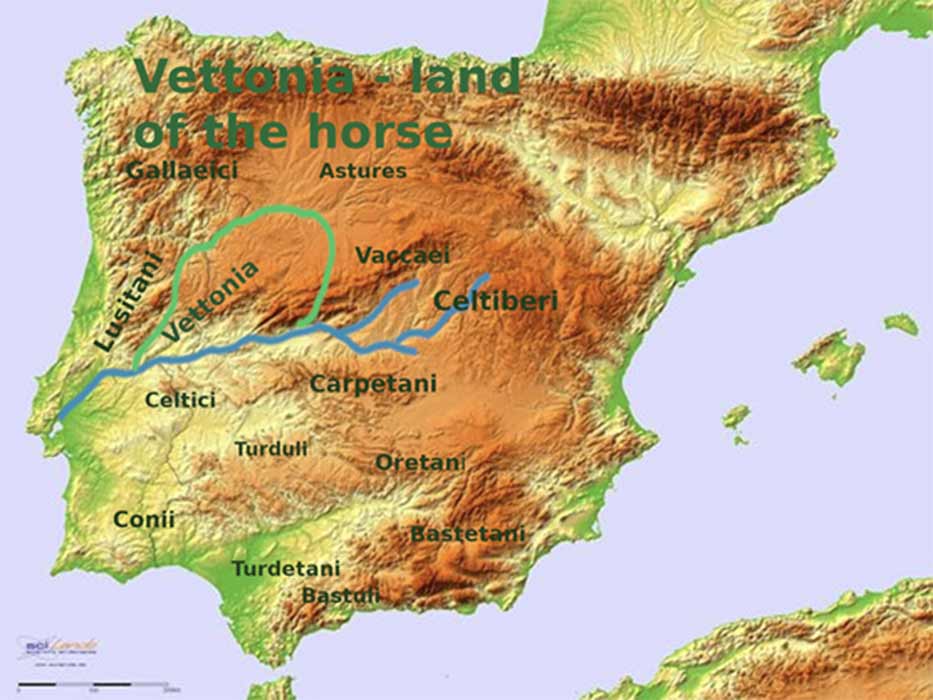

There were the Turdetani in the south, the Galaici in the north, the Lusitani, the Celtici, the Vettones, the Conii, the Montanhenses, the Celtiberi, the Vaccei, to name a few. These were confederations, holding smaller clans or tribes. Each clan had its hillfort home. The tribal confederations all shared a common cultural identity, Celtic, and particularly in the more mountainous Iberian terrains, a hillfort culture.