Ignoring Omens and Seeking Vengeance: The Greco-Persian ‘War of the Ages’ Was a Disaster for All

The Greco-Persian wars lasted for more than half a century in some respects. Some date the war as being from 499-448 BCE while others date the conflict from 492-448 BCE. Either or, the war itself was a disaster for both sides.

The Greeks, during the war with Persia, even fought amongst themselves in the First Peloponnesian War from 460-445 and then again in the Second Peloponnesian War from 432-404 BCE. For their part, the Persians lost territory during this conflict with the various Greek states and in doing so, lost a sense of supremacy in the region. On a darker note, Persia’s losses also fueled Greek supremacy, which would eventual lead to the rise of one Alexander the Great of Macedonia. Alexander, as we know, would invade Persia and conquer it without hesitation. Nevertheless, it is not the focus of this piece to delve into the various Greek wars or Alexander’s invasion of Persia, but rather look into how and why the Greco-Persian wars started in the first place!

Who and what caused the war that we read about today or see glamorized in Hollywood films? Was the whole thing manufactured by one side?

The Warnings of the Oracle

When Cyrus the Great of Persia defeated Astyages, the last king of the Median Empire in 559 BCE, he inherited a new problem. That problem was the western frontier in what is today the country of Turkey. Beforehand, in 585 BCE, the Medes and Lydian empires made an agreement that the Halys River would be the boundary between the two powers. The king of Lydia at the time was Croesus.

Croesus was famous for his wealth and power throughout Greece and the Near East. With his brother-in-law Astyages now defeated, he felt the need to avenge his defeat. In reality, he saw this as an opportunity to extend his borders. Nevertheless, before Croesus mobilized his forces he sent embassies with many gifts and they asked the oracle of Delphi questions concerning the Persians. The oracle turned to the men and said, “If Croesus attacked the Persians, he would destroy a great empire.” The oracle also suggested to Croesus that he should seek some allies that were powerful to assist him in his war against Persia.

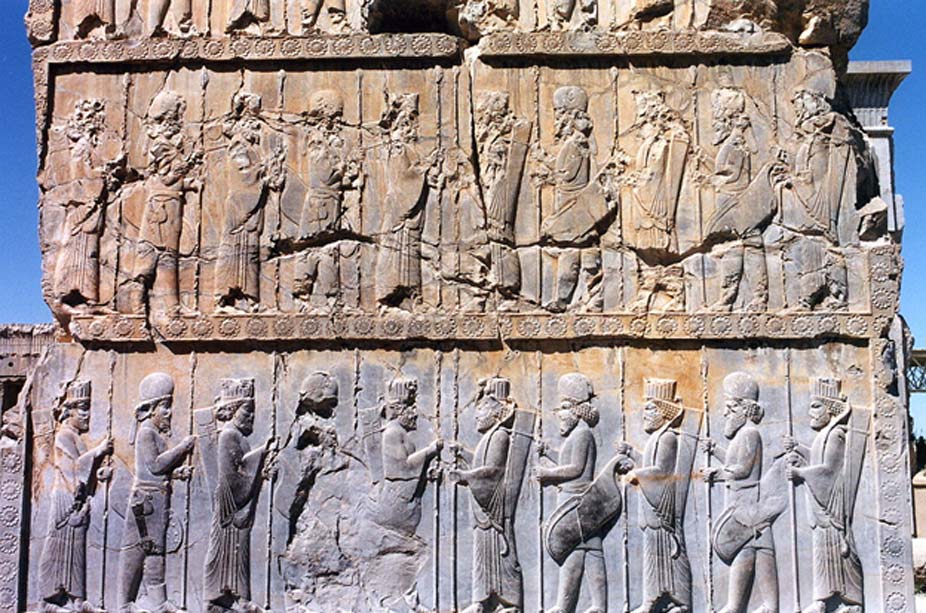

Relief of Persian and Median warriors (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Croesus became overjoyed and overconfident about the news. One would think that Croesus would have understood the part about finding some allies to assist him in this war with Persia as the advice given suggests that Persia’s might was far greater. Nevertheless, Croesus visited the oracle again, and asked how long the Lydian empire would last. The oracle said to Croesus “Wait till the time shall come when a mule is monarch of Media: Then, thou delicate Lydian, away to the pebbles of Hermus: Haste, oh! Haste thee away, nor blush to behave like a coward.”

The mule, a hybrid animal of a donkey and a horse, that is mentioned symbolized none other than Cyrus, for Cyrus was part royalty due to his mother being an Umman-manda princess, while his father Cambyses was a petty vassal king or quite possibly a mere tribal chief in the eyes of Astyages. One can easily base these judgements on ethnicity, but the people we are dealing with were of semi-nomadic stock, and it seems that some had more privileges than others did due to royal status rather than ethnic diversity.

A Critical Error

In 547/46, BCE, Croesus moved his forces beyond the Halys River and entered into the province of Cappadocia. Once there, he sent envoys to Croesus’ camp with a message ordering Croesus to hand over Lydia to him. If Croesus agreed, Cyrus would allow him to stay in Lydia but would have to remove his crown as king and he’d need to accept the title Satrap of Lydia. Evidently, Croesus turned down the invitation and the two armies did battle instead at a place called Pteria in Cappadocia. The battle took place in the month of November and Croesus was defeated, and he retreated across the Halys River and back into Lydian territory.