The Iliad And The Odyssey: Lessons From Humanities

The Humanities are by definition concerned with humankind’s life-chances and life-fates, and mortality captures humanness from one essential viewpoint – all humans inevitably die. All human life, and too often death, feature in the monumental poems The Iliad and The Odyssey. Mortality is there in both of Homer’s poems – hundreds of Greeks and Trojans die in The Iliad, all Odysseus’ men are gone before the hero regains his home of Ithaca. But it is not the umbrella concept of either poem, though it is far more so in The Iliad than in The Odyssey. The Odyssey recalls the eponymous hero Odysseus’ trials, travels, travails and tribulations and Odysseus after all, lives literally to tell his tale – or (often tall) tales. As for Achilles, he is still very much alive and kicking at the end of The Iliad; his death will not be related until later, in a poem of the so-called Epic Cycle.

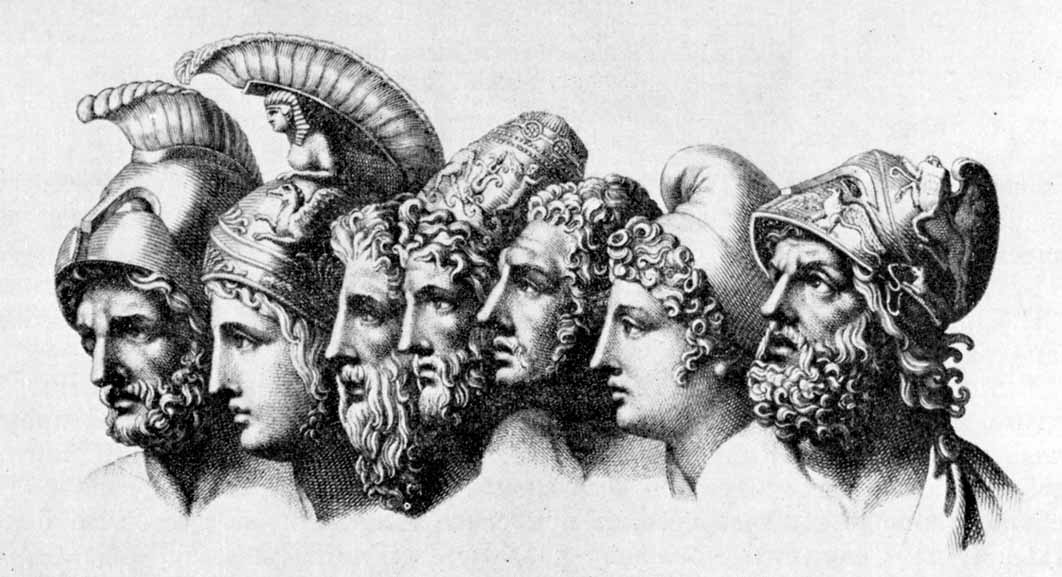

Heroes of The Iliad by Tischbein. (Public Domain)

For the ancient Greeks, the gods and goddesses were precisely the ‘not-mortals’, a-thanatoi. The poems are often said to be the ‘Bible’ of the ancient Greeks, but actually the pagan, polytheistic Greeks did not have any officially recognised sacred books. And although both poems are full of gods and goddesses and their interactions, both negative and positive, with humans, they are not teaching religious dogmas. What the ancient Greeks saw in The Iliad and The Odyssey were rather models of mostly individual human behaviour both to imitate – and to avoid like the plague. Perhaps politicians embroiled in current warfare can take a lesson or two from these.

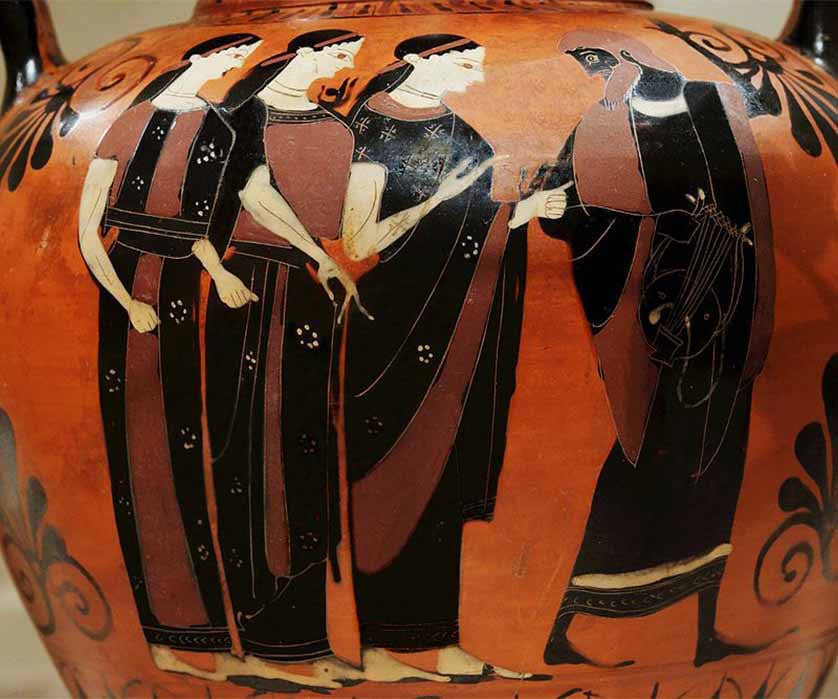

Judgement of Paris. Attic Black-Figure Neck Amphora by Swing Painter (c. 540-530 BC) Metropolitan Museum of Art (CC BY-SA 2.5)

Themes of The Iliad and The Odyssey

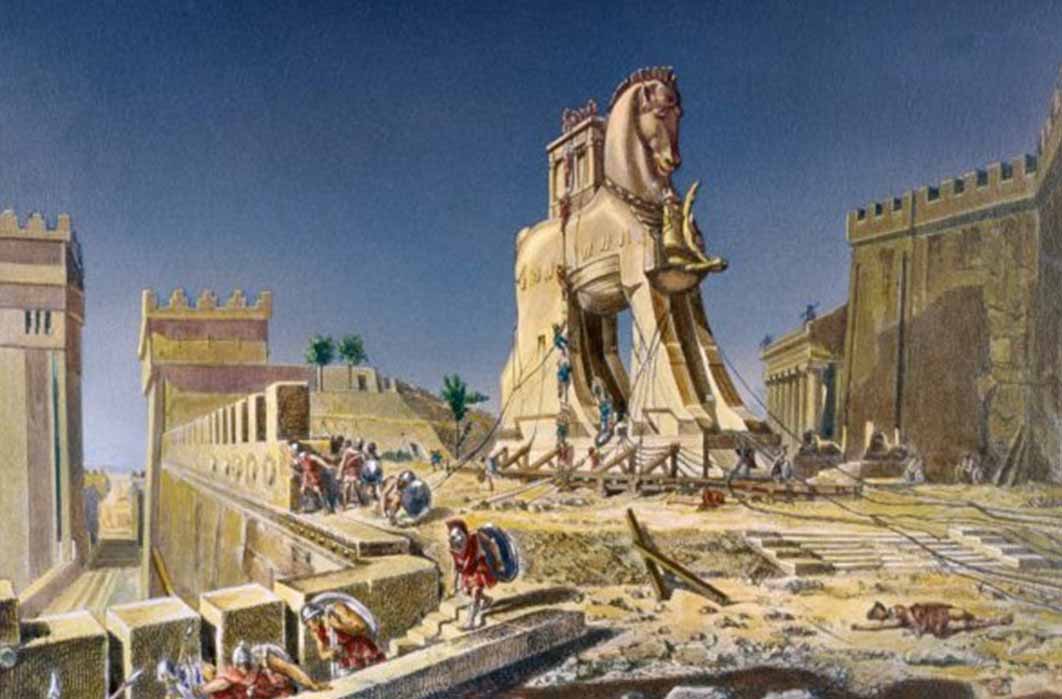

In nutshell the storyline of The Iliad comprises the theft of Helen, Queen of Sparta, by Trojan Prince Paris, considered a gross breach of hospitality etiquette as well as of sexual immorality, and its attempted rectification. The theft is elaborately prepared by the mythic ‘backstory’ of Paris’ ‘judgment’ conspired between the three mighty Greek goddesses Athena, Hera and sex-goddess Aphrodite, whom – naturally – the youthful Paris decides is ‘the fairest’, and so he wins Helen. So, it is really Paris and not Helen who ‘causes’ the Trojan War, though later Greeks focused far more on hers than on Paris’ guilt. Homer of The Iliad plunges into the thick of it, many years later, almost ten years to be precise after the seduction/abduction of Helen, since the action of The Iliad is confined to a few weeks, a couple of months, in the tenth year of a (historically impossible) ten-year siege. The poem should really be known as the Achilleid since Homer’s narrated action is focused all around Achilles and his piqued rage, which is directed chiefly at the supreme Greek commander Agamemnon, King of Mycenae and brother of Helen’s cuckolded husband Menelaus.

Polyphemus throwing rocks at Odysseus and his crew, by Arnold Böcklin (1896) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Public Domain)

Regarding the theme of The Odyssey, as a historian specializing in early-historical Greece, Dr Paul Cartledge (University of Cambridge) favours the view that – apart from all the excitements, the sheer picaresque narrative thrills involving ogres and monsters of many kinds – it is mainly all about Greekness or, to be more accurate linguistically, Hellenicity - in Homer Greeks are not called Hellenes but ‘Danaans’, ‘Argives’ or ‘Achaeans’. How to be a Hellene in a world that was rapidly changing both geographically and culturally. It has always been a bit of a puzzle that the epic should focus on the ruler of a petty island-kingdom on the far west of mainland Greece, but the reason for that choice was mainly twofold: Ithaca was as far away from Troy while still being old-Greek as it was possible to get without leaving the mainland, and an ultimate western setting reflected the fact that from about the middle of the eighth century BC Greek traders, adventurers and settlers were moving west, some of them permanently, to south Italy and Sicily, passing by Ithaca en route.