Parallels Between The Jewish Fall Festival And Akhenaten’s Royal Jubilee

A deep mystery haunts the origins and rituals of the Jewish Fall Festivals: Rosh Hashanah (New Year), Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), and Sukkot. Representing more than individual holidays, these festivals comprise a three-week period in autumn marked by holiness, remembrance, celebration, and joy. However, very little is known about how they came about. The Bible indicates Moses first decreed them, long before Israel became a country. Oddly, Moses was vague when explaining why, and in many cases he provided no reason at all. This leaves a peculiar void when trying to explain the meaning of these enigmatic Jewish ceremonies. For example, why shout and blow the shofar ram’s horn on Rosh Hashanah? Why focus on personal death and rebirth on Yom Kippur? Why build a wooden structure out of plants and then celebrate in it with family on Sukkot? Without a new understanding of the past, any answers remain frustratingly elusive.

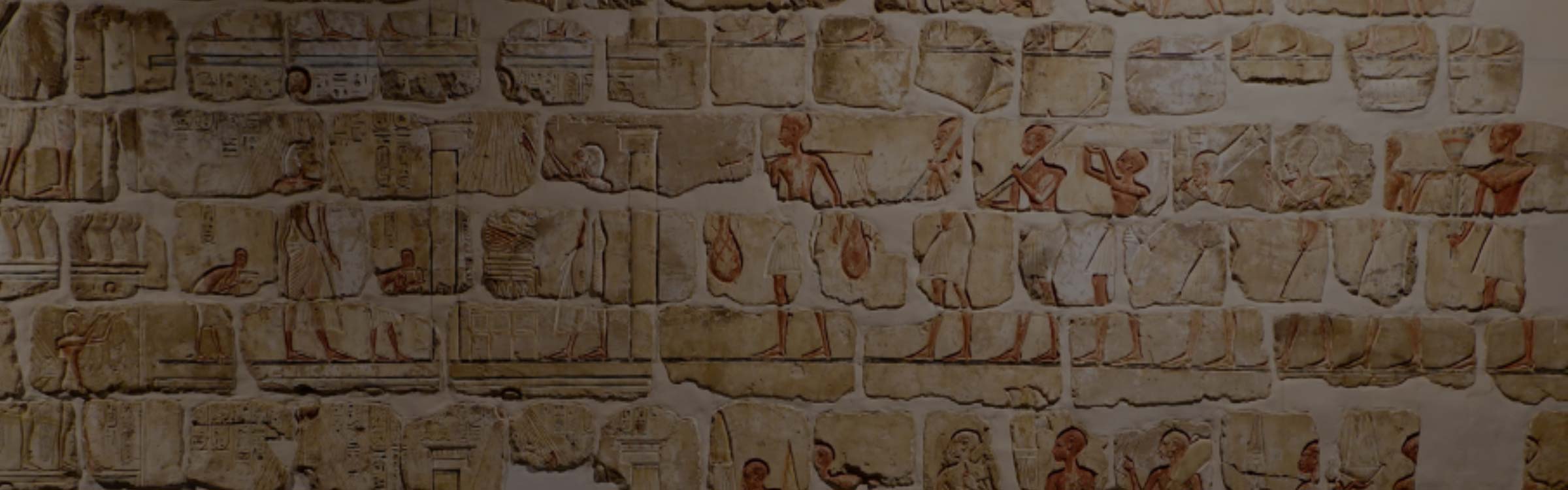

Depiction of the Heb-Sed of Senusret III (1878-1839 BC) showing the king in his baldachin as both king of Upper and Lower Egypt, and receiving the gift of palm ribs from Horus and Set. These signify long rule. (Soutekh67/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

Link To Akhenaten’s Heb-Sed

The current author proposes a radical new theory: that these rituals and observances seem ancient because they are ancient, and that the three weeks of fall festivals actually represent one single memorial period of Pharaoh Akhenaten’s Royal Jubilee Festival, or Heb-Sed. This was a multi-week-long coronation-renewal event celebrated across Egypt and was very similar to how the early Israelites viewed their autumnal holy days: as one single festival with several holidays marking its key points. This would have only been possible if Akhenaten, the monotheistic sun pharaoh is connected with Moses, the monotheistic Hebrew lawgiver. There is an astounding array of parallels between Jewish fall celebrations and those of the ancient Egyptian Jubilee festival.

Old Kingdom Pharaoh Niuserre wearing his Heb-Sed robe and sitting in his baldachin. Limestone from Niuserre’s Sun Temple at Abu Ghurob; (2390 BC). Staatliches Museum (Khruner/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Egyptian Royal Heb-Sed

The Egyptian Heb-Sed, Festival of Sed, or Jubilee, was a kingship-renewal ceremony that was usually held after a pharaoh ruled for 30 years. Edouard Naville first studied it in 1892, and it entailed, as Egyptologist Greg Reeder explains: “a rejuvenation of the king and, by proxy, all of Egypt.” Rachel A. Grover notes it is: “one of the most mysterious of the ancient Egyptian festivals.” The hieroglyph of the festival was a baldachin, a portable chapel set on a raised dais with the two thrones of Upper and Lower Egypt, set on a heb bowl glyph meaning ‘festival’.

Alabaster offering vessel of Pepi I, Old Kingdom (circa. 2300 BC), made for his 30-year Heb-Sed. Trio of Heb-Sed hieroglyphs circled in red: the Sed chapel with double empty thrones, the Sed hall glyph, and the alabaster bowl glyph meaning festival. Walters Art Museum (Public Domain)

It was also one of Egypt’s oldest festivals, originating in pre-dynastic times to honor the ancient wolf god Sed. Djoser, the Third Dynasty ruler who built the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, included in his complex a Jubilee court with a throne dais and two rows of stone shrines - Mansions of the Heb-Sed - that faced each other across the courtyard. These were, as Reeder notes: “erected on the archaic pattern of the reed-hut sanctuaries of prehistoric days.”