Formidable Medieval Queens Triumphing Kings And Popes

In January 1077 a king came to the mountain fortress of Canossa in northern Italy to beg forgiveness from a Pope. In September 1141 two rival armies surrounded Winchester in southern England as besiegers became besieged. In January 1194 a ransom was paid to free an English king held captive in Germany. What all these incidents have in common is that, most surprisingly for the Middle Ages, in each case women were major players in the game.

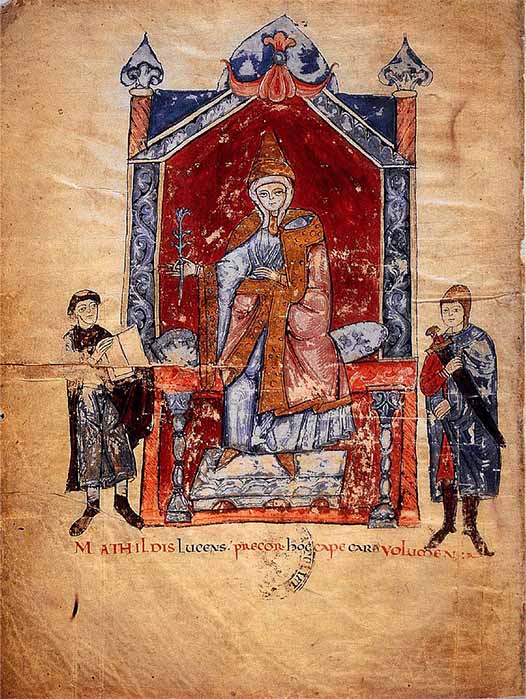

Miniature of Matilda from the frontispiece of Donizo's Vita Mathildis des Donizo, (1115) Vatikanstadt (Public Domain)

Matilda of Canossa

Matilda of Canossa also called Matilda of Tuscany, was barely 30 years old when she became involved in the incident that would define her life. Bold, strong-willed, educated and trained to command, she bears little resemblance to the weak and subservient stereotype of medieval women, save, perhaps, for her love of the church. Coming from the line of Counts of Canossa, the death of her father, Boniface, in 1052, quickly followed by that of her brother in 1055, had left her sole heiress to the Margravate of Tuscany and to the many other independent estates Boniface had acquired in northern Italy. The Margravate was held from the Holy Roman Empire, and in the struggle between Pope and Emperor that became known as the Investiture Controversy, the role of Tuscany, and Matilda in particular, would become decisive.

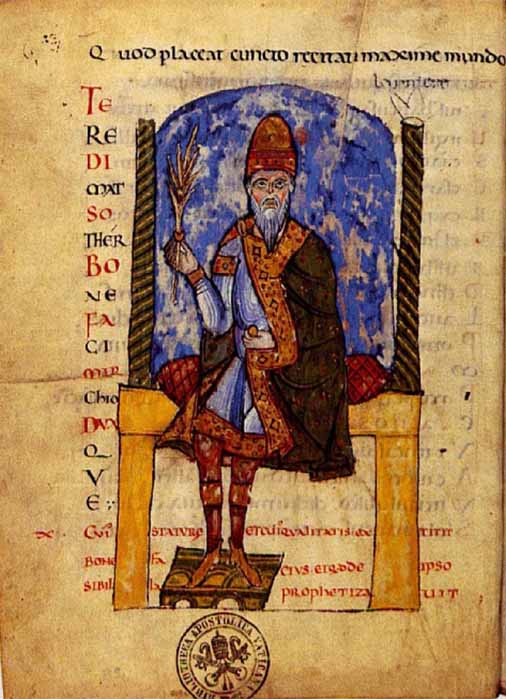

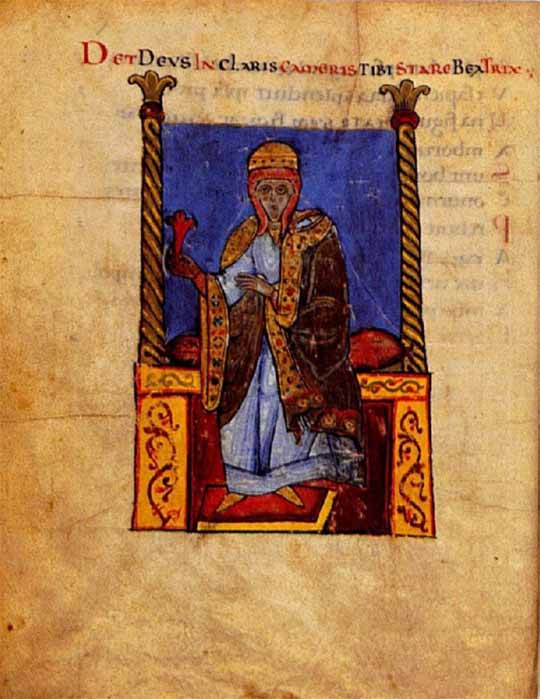

Matilda's parents, Boniface and Beatrice. Donizo's Vita Mathildis. Vatican Library. (Public Domain)

This controversy was a matter of some importance to the Emperor since, from the mid-tenth century much of the administration of the Holy Roman Empire had been entrusted to bishops and archbishops. The Emperor had appointed whoever he wished to these posts, these men being the backbone of his regime. By tradition he also invested them with ring and crozier as symbols of their office. In addition, as coronation by the Pope was necessary to make the King of Germany and Italy into Emperor of the Romans, for a time, appointment of the Pope himself was controlled by the Emperor. Empire and Papacy had thus become closely entwined.

From the mid-11th century, however, pressure for reform of the Western church grew steadily, with northern Italy particularly strong in the reforming party. The influence of Hildebrand, archdeacon and papal administrator and a Tuscan himself, was behind a string of reforms, in particular a declaration that only cardinals could elect a Pope, although for a time the Emperor’s approval was still sought. Matters were taken to a new level, though, with the election of Hildebrand himself as Pope Gregory VII in 1073.

He now declared that appointing and deposing senior clergy was a matter solely for him, and ‘lay investiture’, as practised by the Emperor, must not take place. Further, in his ‘Dictatus Papae’, the Dictates of the Pope, written in 1075, he claimed the Pope as supreme head of the church was answerable to no-one, that all princes were to kiss his feet, and that he had the power to depose kings and emperors and free their subjects from their oaths of loyalty.