Chasing The Heavens: Ancient Observatories of the Yucatán Maya

Centuries ago, Maya astronomer-priests charted the heavens from huge stone observatories. From above the jungles of the Yucatán in modern-day Mexico, they carefully recorded the motions of the gods above: the sun, moon, stars and planets, and planned out their lives accordingly; when to sow, harvest, sacrifice, and make war – these were all decided by the heavens.

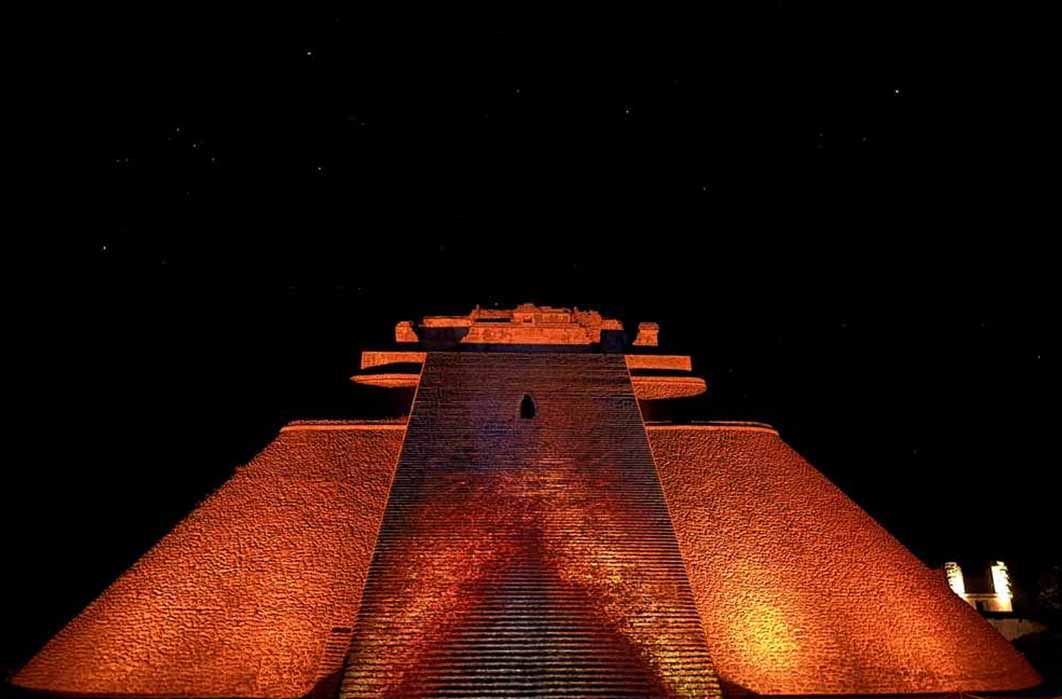

El Caracol, the Observatory- at Chichén Itzá. The building as a whole is aligned to the northerly extremes where Venus rises. (Image: © Jonathon Perrin)

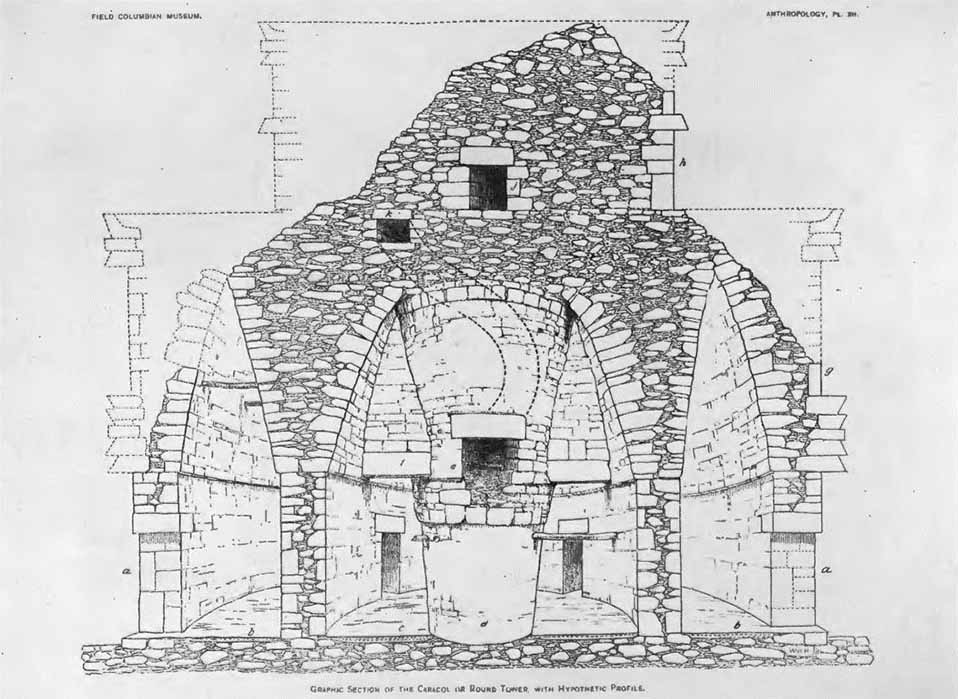

Covered in jungle and crumbling blocks, a ruined mound – that is how the ancient circular building known as El Caracol in the Maya city of Chichén Itzá, was first described by early explorers almost two centuries ago. Even then it was called an observatory, but only because its hemispherical-shaped ruinous state resembled contemporary European-style optical observatories. The irony is that this strange stone edifice actually did at one time function as an observatory for the ancient Maya astronomer-priests who ruled in Chichén Itzá. It did not however look like modern rounded observatories but was actually cylindrical with a flat roof, and was originally described as unattractive by early Europeans.

A high platform, reached by a narrow spiral staircase and surrounded by a stone wall riddled with precisely sized windows and holes, enabled these priests to observe at least 20 different astronomical alignments throughout the year. They did not use optical telescopes with lenses, but rather performed “naked-eye” astronomy from above the jungles of flat-lying Yucatán. By following the movements of the celestial bodies over the years, and carefully recording their changing positions, they created a form of agro-astronomy which let them precisely time when to prepare fields, and plant and harvest each crop, including the primary Maya staple – corn.

Updated interior plan of the Caracol, drawn by William H. Holmes in 1895. Clearly visible is the interior spiral stone staircase which would have allowed access to the second-floor viewing platform. Rupert, Karl, The Caracol at Chichen Izta (sic) Yucatan, Mexico, Carnegie Institution of Washington (1935).

Not always uniform in plan, Maya observatories were in fact all quite unique, and represented different cultural traditions manifest in stone buildings. Some were pyramids, usually elliptical, such as the Pyramid of the Magician at Uxmál or the Observatory at Cobá, while others were actual circular buildings, such as the Round Temple at Mayapán or El Caracol at Chichén Itzá. Still others were quadrilateral, such as the Temple of the Seven Dolls at Dzibilchaltún. All however allowed the Maya astronomer-priests to perform their service to the gods while tracking the motions of the sun, moon, Venus, Mars, the Pleiades (a bright star cluster which the Maya believed was a giant rattle of a snake), and more.

The Maya recorded the motions of the heavens in painted wooden codices, only four of which now survive in European cities (the rest were burned in fits of religious zeal by early Spanish priests). They could predict eclipses and other cosmic occurrences far in advance, and much of the ritual and government of their society, including the instalment of kings and the timing of wars, was entirely dependent upon events in the skies.

The Sun God Kinich Ahau

The Maya oriented their huge stone civic and religious buildings according to astronomical phenomena of the cosmos, principally the sun. They also encoded key astronomical information into the decoration of their buildings. According to Michael Grofe: “It is generally agreed that Mesoamerican architectural alignments commemorate repeating celestial observations of horizon-based azimuth positions. Most obvious and familiar among these are those that suggest references to the rising and setting positions of the sun on the solstices and equinoxes.”