Ancient Markers of Traumatic Events: The Era of Menophres, Sothis, Osiris, and Noah

In his work De Die Natali (The Birthday Book), written in 238 AD, Censorinus, a Roman grammarian and author, discusses the concept of the Great Year in Chapter XVIII. He writes “The 1461st year by some is called the Heliacal and by others the Year of God.” In Chapter XX he states that the current Annus Magnus had commenced a hundred years earlier in 139 AD. Working back from this date 1461 years brings the date to approximately 1322 BC. This is confirmed by an extant text written by the astronomer Theon of Alexandria (c. 335 AD- 405 AD). He refers to it as the Era of Menophres.

There is much debate as to who Menophres was, with some maintaining that the name is little more than a geographical reference to Memphis. The greater likelihood is that the name relates to a pharaoh, and a number of candidates clustered around that date have been proposed. The prime candidate in the author’s estimation would be Seti I (c.1294 or 1290 BC to 1279 BC). His birth is currently dated c. 1323 BC, within a year of the target date, and within 4 years of the c. 1327 BC date for the destruction of Ephesus/Atlantis. Tutankhamen’s demise is dated to the same year, 1327 BC. Is it coincidental or was there something else in the equation?

The Tetraëteris Problem

Notably there exists a problem in reckoning time known as the tetraëteris, the four-year phase during which the heliacal rising of Sirius was observed on the same day of the year. Every four years the phase moved backward one day, and it is not possible to determine in which of the four years of the tetraëteris a given observation took place. Censorinus’ use of the year 139 has been questioned with 136 seeming to have been the start of the tetraëteris. If so then this would produce a date for the start of the cycle of c. 1325 BC - a date within a year or two of the natural disaster which destroyed Ephesus!

Volcano

Seti I came to power in the aftermath of the momentous events surrounding the demise of Arzawa. He would have been considered as blessed by the gods when he came to rule, since the main beneficiary in the aftermath of the disaster proved to be Egypt. The details concerning the c. 1327 BC eruption can be found in the author’s book entitled Atlantis, the Amazons, and the Birth of Athene. It would also help explain why he adopted the name Seti/ Seth - which in effect is a metaphor for an active volcano. The Greeks equated Seth with Typhon; one only has to read descriptions of Typhon for confirmation of this premise.

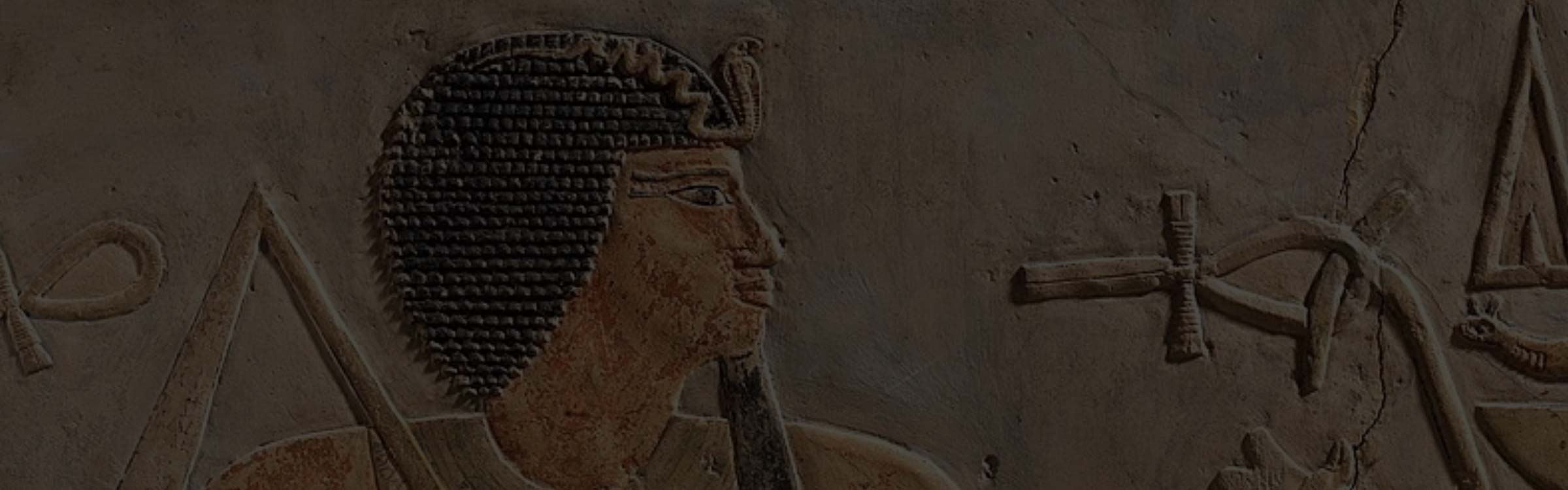

Image of Seti I from his temple in Abydos, Egypt. (Messuy / CC BY-SA 3.0)

It is curious given all the debate about the volcanic eruption of Thera, that little if any attention seems to have been paid by modern scholarship as to why the Egyptian pharaohs suddenly adopted names linked to volcanic metaphors (Ptah depicting a quiescent volcano, and Seth depicting an eruption) centuries after the surmised date for the eruption of Thera. Interestingly, modern researchers appear to be becoming increasingly aware of another potential source of volcanic eruption during this period.

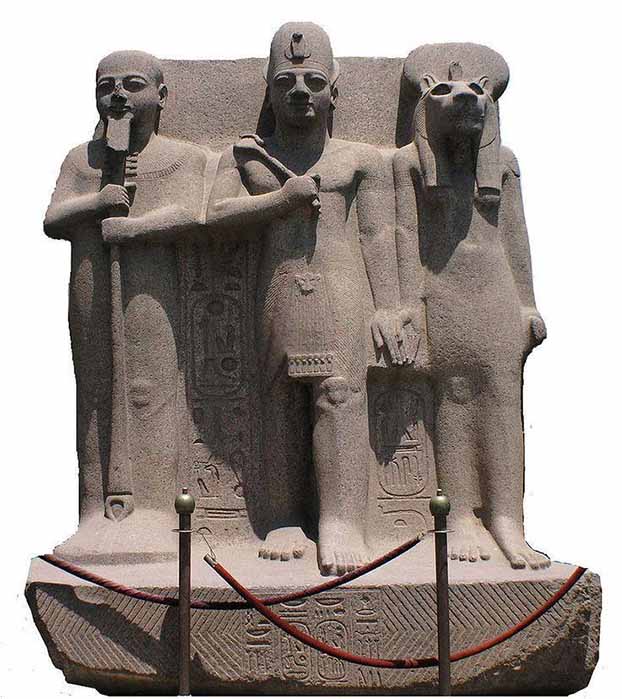

Tellingly, on his accession Seti embarked upon a series of successful military exploits (encouraged no doubt by the chaos in western Asia Minor). In Egypt he instituted a major building program as well as engaging in the restoration and repair of older monuments which had been vandalized during Akhenaten’s reign. The work was continued in his father Rameses II reign. Notably a ‘selfie’ carving of Rameses II exists depicting him with his pals: Ptah and Sekhmet.

Rameses II with his pals Ptah and Sekhmet. (Daniel Mayer / CC BY-SA 3.0) Deriv.