The Recognition Of Monarchy Through History

The well-known story of the Roman Emperor Hadrian’s rebuke at the hands of the petitioner whom he had rebuffed is significant. “Then, don’t be king!” was her taunt, illustrating the general expectation in a strong popular monarchy that the ruler should be accessible by even the humblest of his subjects. Similar stories are associated with several other rulers in antiquity. Such accessibility is a reflection of the close bond or even symbiotic relationship between strong rulers and their subjects based on mutual dependence.

Statue of Hadrian in military garb, wearing the civic crown and muscle cuirass, from Antalya, Turkey (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The power structure in every society is such that there is a natural antipathy between the ordinary people on the one hand and, on the other, the aristocracy, the wealthy or a privileged elite, whose ambition it always is to acquire power, which is then exercised in an oligarchic form in their own interest and against the interests of the masses in an oligarchic form of government. The only way the masses can overthrow such an oligarchy is under the leadership of a champion, who may in his own person have emerged from the ranks of the privileged but who recognizes that his springboard to power is popular support against the privileged elite. By the same token, the masses gain protection from their champion against the privileged elite. A hereditary monarch can also avail himself of this same feature of the power structure by recognizing that there is a natural alliance of monarch and people against the privileged elite.

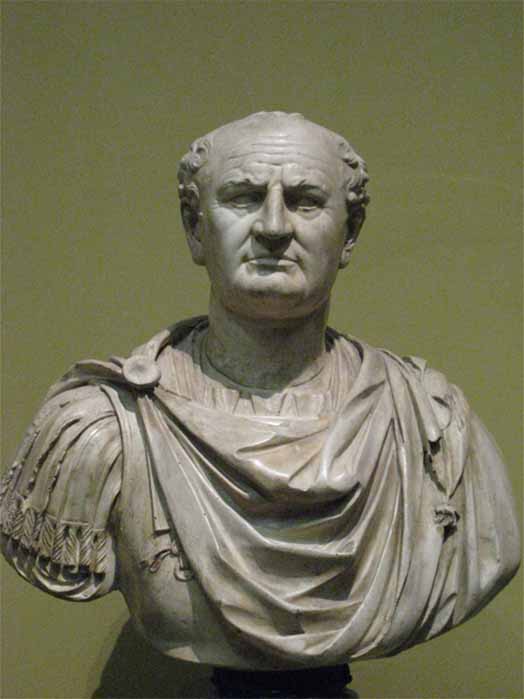

Vespasian, rose from the ranks to become Emperor of Rome and on his deathbed rumored to have murmured: Vae, puto deus fio. Translation: "Oh dear, I think I'm becoming a god! (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Understanding power structure has been very rare throughout history, among politicians, rulers and historians alike. Prime examples of leaders who did understand it include the Roman Emperors Augustus, Hadrian and Constantine, and in modern times Argentina’s Juan Perón (and even more so his first wife Eva), Cuba’s Fidel Castro, and China’s Mao Zedong and Xi Jinping. One of the very few historians ever to have had any insight into this crucial issue was Niccolò Machiavelli. No recent historian, whether living or dead, has shown the slightest understanding of it.

King Alfred depicted in the early 14th-century Genealogical Chronicle of the English Kings (Public Domain)

Going Incognito

Images of rulers, monarchs and political leaders are plastered all over the media, to the point where high-profile figures like Hitler, Stalin, Vladimir Putin and Saddam Hussein are suspected of having resorted to using “doubles” for reasons of security. The flip side of this is stories of monarchs travelling incognito, again either for reasons of security or to sound out popular opinion on their rule. The Roman Emperor Nero (reign 54-68 AD) is reputed to have wandered around Rome in a drunken frenzy under cover of darkness and to have picked fights with brawlers. The well-known story of England’s King Alfred the Great (reign 871-899 AD) burning the cakes has its origin in his attempt to evade capture by the Danes. Taking refuge in a peasant woman’s cottage, Alfred was asked to watch over her cakes in the oven. Never having baked a cake in his life, Alfred allowed the cakes to burn!