Monks, Hermits and Ascetics: The Little-Known History of Women in Desert Asceticism

Theodoret of Cyrrhus (423–457) tells us that when little girls played games in forth-century Syria, they played monks and demons. One of the girls, dressed in rags, would reduce her little friends into giggles by exorcising them. This glimpse into a Syrian childhood scene points to the prestige of the monk figure and may serve as a preview to what must appear in this modern age as a somewhat strange theme in the setting of Christian hagiography—the woman monks of the deserts. Women who disguised themselves as monks and lived as hermits, or as members of the male monastic communities is a recurring theme in the first and oldest layers of Byzantine history.

Scenes from the Lives of the Desert Fathers (Thebaid), 1420. (Public Domain)

As the early Christian church began to flourish under Constantine’s rule in the fourth century Greco-Roman world, so too did the ascetic movement. The early Christian hermits, ascetics and monks known as the “Desert Fathers” who lived mainly in the Scetes desert of Egypt in 3 CE were a major influence on the development of Christianity. This movement was catalyzed by Saint Antony the Great, who is revered as the father and founder of desert asceticism.

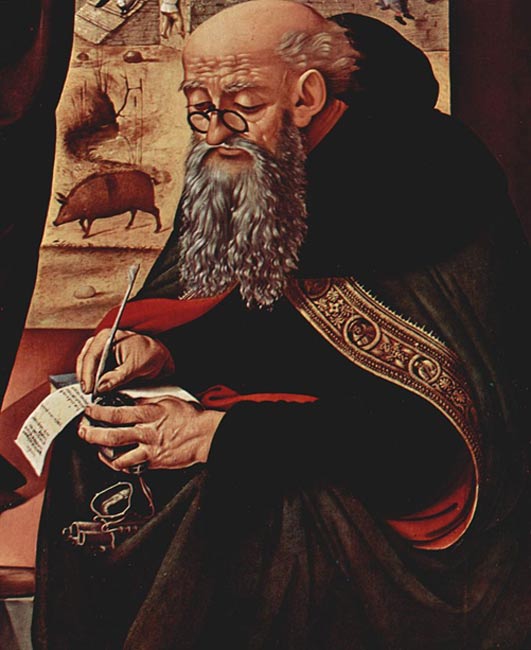

Painting of Saint Anthony by Piero di Cosimo, c. 1480 (Public Domain)

Before Antony went into the desert, he first placed his sister in a community of “respected and trusted virgins,” which indicates that such monastic communities had existed for some time before the Father of Monasticism set out on his desert journey.

One of many artistic depictions of Saint Anthony's trials in the desert. (Public Domain)

There was very little information about the women who looked after Antony’s sister, as well as about the women who decided to follow his example to go to the desert, earning themselves the name of the “Desert Mothers.” Yet, they existed, and some of them were sainted.