Still Searching Aztec Montezuma’s Lost Treasure

The missing gold of Montezuma, ninth Emperor of the Aztec Empire was buried by the Aztecs, the Utes protected it, the Spanish killed for it, and the Mormons looted it, but is the bulk of it still out there? On November 18, 1519, Spanish conquistadors under the command of Hernando Cortés entered the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City, overthrowing indigenous control and imprisoning Montezuma, the ruler of the empire. Cortés had sailed east from Cuba before marching his soldiers overland from Vera Cruz. Their objective was, despite what church leaders wrote about missionary endeavors, to harvest gold and riches. With the capture of Tenochtitlan, their objectives were realized almost beyond belief. The amount of gold they discovered surmounted their wildest dreams. But avarice is fueled by the word “more.” The amount of riches bestowed upon them by Montezuma, who hoped to buy the Spanish invaders off, did not satisfy their greed, it merely inflamed it. Cortés wanted more.

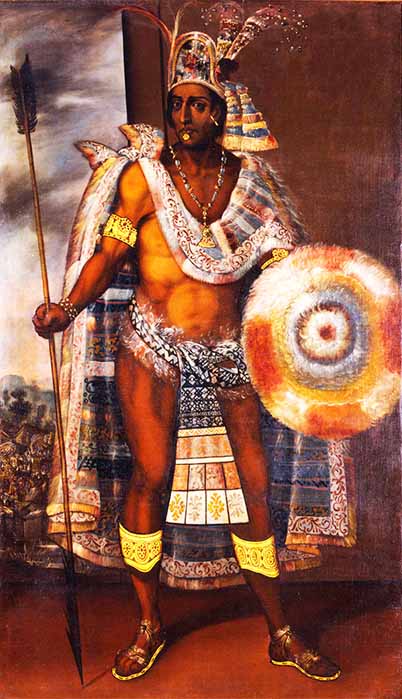

Portrait of Moctezuma II (1466-1520), attributed to Antonio Rodriguez (Public Domain)

Quetzalcoatl The Feathered Serpent God

The reason Cortes’ military objectives were at first so easily obtained was due to an historical mystery that he did not understand at that time. Mesoamerican cultures have different versions of this story, but there are certain commonalities in their tales:

Quetzalcoatl, the ‘feathered serpent’, was chief God of the Aztec religious system. He was represented by Venus, the solar light, and the morning star. His twin brother, Xoloti, was the evening star. In Catholic biblical imagery, Venus is called the morning star. According to Isaiah 14:12, however, the ‘morning star of light’ became a ‘fallen” star of darkness’: “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! How art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations!” In other words, the opposition of Jesus and Lucifer, good and evil, was about to come into fruition in the persons of Quetzalcoatl and Cortés.

Two forms of the god Quetzalcoatl in Codex Laud, (15th century) as the feathered serpent, celestial deity (left) and as the god of the wind Ehecatl (right) (Public Domain)

According to many historians, Quetzalcoatl, the ‘feathered serpent’, or the ‘plumed serpent’ whom many Mesoamerican peoples claim was their ancestor, was an hombre blanco, a white man, with a flowing beard. He condemned sacrifices that polluted the people. He taught them how to use proper cooking fires, and showed them how to "live together as husband and wife." He arrived from the sea "in a boat that moved without paddles," and "taught the people to live in peace." Under different names, he is found in Olmec, Mayan, and Incan oral history as well. Quetzalcoatl was thought to be the inventor of books and calendars. He was the one who had given them maize, or corn. In some religious systems, he had become the symbol of death and resurrection.

If all that did not give him enough to do, he was also related to the gods of the wind, the dawn, merchants, arts, and crafts. He was the patron god of learning and knowledge. He went to the Underworld and created mankind in this, the fifth, or present-day, world. Wind, fire, and earthquakes had destroyed humankind in the previous worlds. According to Aztec legend, the destruction came about because their inhabitants did not worship the gods. Because of the jealous impulses of indigenous priests, who felt threatened by Quetzalcoatl’s success as a religious leader, he was eventually forced to sail away "toward the rising sun." But he left a final message: "I'll be back."

The Mormon Interpretation

According to some scholars who are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Quetzalcoatl was the resurrected Jesus Christ, although this is not the official doctrine of the church. Latter Day Saints doctrine simply teaches that after his resurrection in Jerusalem, Jesus appeared in the New World, carrying on the ministry he had begun in Jerusalem, but it is hard not to paint Quetzalcoatl into this picture.