Napoleon’s Amazing Foresight: Savants, Soldiers and Science

In 1798 the French general, Napoleon Bonaparte, led an expedition to Egypt vowing to annex the country and halt the military and commercial march of the British. But a little over three years later, despite tasting spectacular victories, he abandoned his troops and went back to France when faced with a reversal of fortunes. However, even though Napoleon’s campaign on Egyptian soil met an abrupt end, not all was lost. Thanks to his savants, in a masterstroke, he converted his failure on the battlefield into a magnificent cultural success that would benefit generations of Egyptologists.

Frontispiece to Description de l'Égypte, published by the French government from 1809 to 1824. © 2018 Dahesh Museum of Art. (Public Domain)

Rediscovery of Egypt

The French Commander-in-Chief, Napoleon Bonaparte, had taken around 170 leading savants (scholars) of the French Commission des Sciences et des Arts (Commission of Sciences and Arts) along with him on his Egyptian campaign. The Commission comprised an almost unbelievable assortment of learned men, and among the travelling party were painters, architects, botanists, draughtsmen, antiquarians, astronomers, engineers, zoologists and even musicians.

This impressive roster of intellectuals fanned out across the length and breadth of Egypt researching and recording, among other subjects of study, extraordinary vestiges of ancient architecture. In the early days of their landing, military personnel ill-treated and insulted the savants whom they held squarely responsible for making them endure the intolerable conditions by providing wrong directions as they headed across the desert to Cairo.

The bitter truth was that the weather was the culprit: the French troops had set foot in Egypt wearing heavy uniforms when the heat was unbearable. The fact that the food supply was running out fast did not help matters. But, with the passage of time, the two groups began to see eye to eye; and the soldiers who were appreciative of the output of the scholars participated wholeheartedly in their efforts.

As the work progressed, it became amply evident that ancient and modern Egypt were not all that hard to conceptualize because of the commendable contributions of the prolific French cartographer Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville (1697 - 1782). Napoleon’s team took a leaf out of such sterling past examples and built upon them greatly - and with complete dedication. Also, due to the diligence of the ten Orientalists who worked as translators, in 1799, the word ‘orientaliste’ was recognized in its modern French meaning of one who studies or paints the Orient.

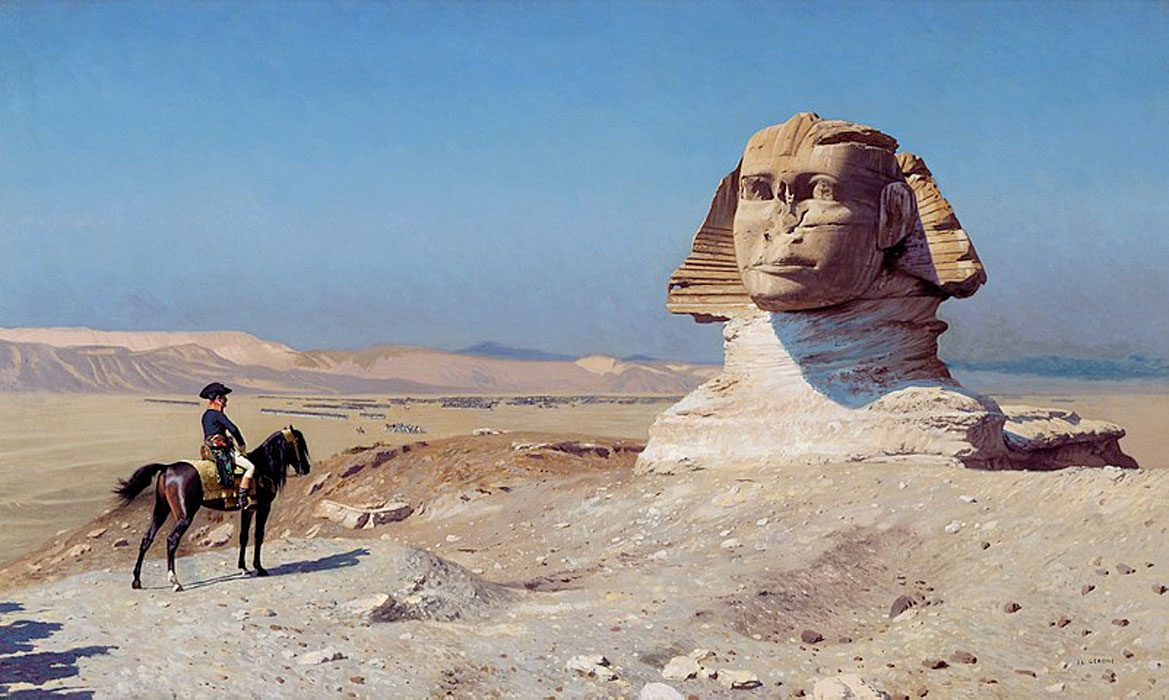

Napoleon at the Battle of the Pyramids, 21 July 1798, oil on canvas, 1810. By Antoine-Jean Gros. (Public Domain)

In the second month of the campaign, Napoleon established the Institut d’Égypte or Egyptian Scientific Institute in Cairo on 22 August 1798. The aim of this institute was to conduct research during his Egyptian Expedition. Today, it ranks as the oldest such institution in the whole of Egypt. The society first met on 24 August 1798, with Gaspard Monge (1746 - 1818) as president, and Napoleon himself as its vice-president.