The Tainted Love Life Of Nero, Fickle Emperor Of Rome

In 49 BC, Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero sent a letter to his friend Atticus informing him about the current gossip in Rome. This time, the big news involved the famous Mark Antony. “Marcus Antonius,” Cicero writes in disgust, “is carrying Cytheris about with him in an open litter, like a second wife.” Apart from being Antony’s mistress, Cytheris was also a famous actress who was known to be the mistress of several other notable Roman leaders. Cicero was even more surprised two years later to find Cytheris at a dinner party, reclining in a position of honor next to the host, as if she were the lady of the house, instead of a lowly mistress. After the party, Cicero immediately wrote to his other friend Paetus to express his outrage. Considering Cicero’s apparent fury about Antony and his mistress, one could easily envision him being well-nigh having a heart attack if he had lived to witness Emperor Nero’s relationship with his wives and lovers many years later.

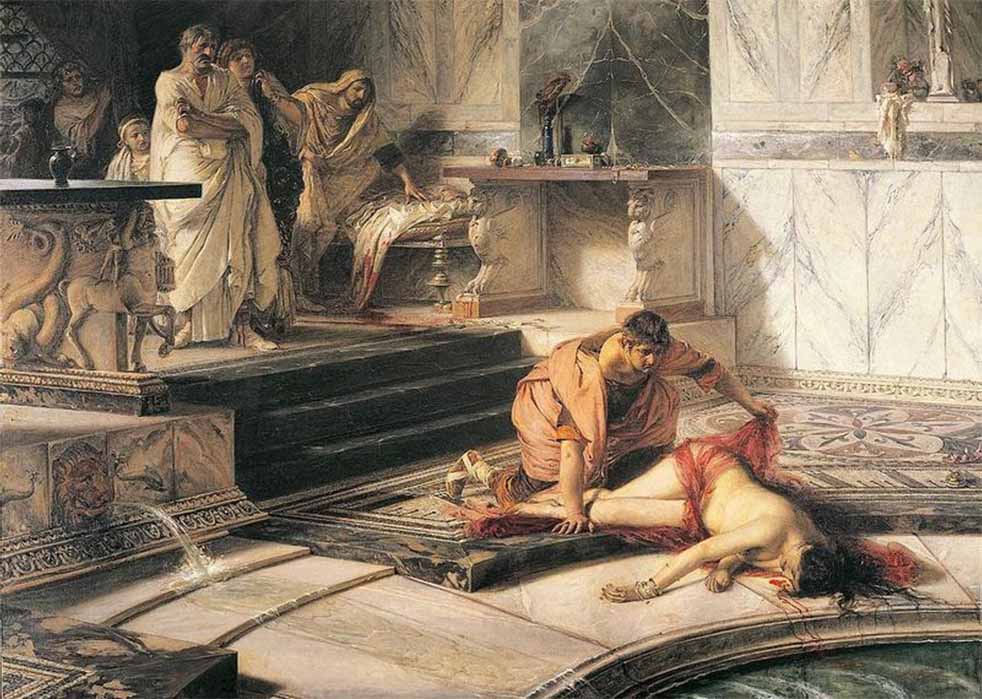

Remorse of Nero by John William Waterhouse (1878) (Public Domain)

The life of Emperor Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus was brief but colorful. His marriages and relationships were also brief and colorful, with most of them ending on a gruesome note. He forced his first wife, Octavia, to commit suicide and kicked his second wife Poppaea Sabina to death during her pregnancy after she reprimanded him for arriving home late from the races. In 66 AD, Nero compelled consul Marcus Junius Vestinus Atticus, the husband of his former mistress Statilia Messalina, to commit suicide so he could marry her. Then there were his lovers, among them Acte, Pythagoras and Sporus.

Claudia Octavia, the Neglected Young Empress

Born either in the late 39 AD or early 40 AD, Claudia Octavia was the only daughter of Emperor Claudius by his third wife, Valeria Messalina. When she was about eight years old, her father had her mother executed and proceeded to marry his fourth wife, her cousin, Agrippina the Younger. Nero, two or three years Octavia’s senior, was Agrippina’s son from her marriage to Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus.

Octavia as a child, statue at the Archaeological and Art Museum of Maremma in Tuscany (Public Domain)

To the surprise of most people around him, Claudius began to show preference towards Nero as his successor over his own son Britannicus (Octavia’s brother). In 50 AD, Claudius officially adopted Nero and bestowed upon him the title Princeps Iuventutis (“Prince of Youth”) a year later. Arranged by their parents, Octavia married her adopted brother Nero in 53 AD. Claudius died the following year at the age of 63, just before Britannicus attained the age of legal manhood, which was 14 years. Apart from Agrippina’s scheming to have Nero declared Claudius’ heir and Claudius’ evident favouritism towards Nero, Britannicus’ age alone would disqualify him from being pronounced Emperor as he would have been too young to rule Rome alone.

Although their marriage appears to have been loveless and childless, when Nero succeeded Claudius as Emperor, Octavia was made Empress. This did not mean, however, that she became a powerful woman. Nero’s mother, Agrippina, was the most powerful woman in the Roman political sphere. However, Nero grew to despise his mother and declared his independence from her at the age of 18. Only two years after his marriage to Octavia, Nero fell in love with a former slave named Claudia Acte and began an affair with her. Acte was a freedwoman from Asia Province and, while she was not a professional prostitute, her ambiguous status as one of many royal concubines gave her the same social standing as Cytheris.