Tracing Scotland’s Neolithic Civilization Back To Armenian And Sardinian Roots

Around 5300 BC a revolution occurred on Orkney. A group of unnamed astronomers and seafarers dared to sail across one of the most hostile waterways in the world to establish the earliest stone circles in the British Isles, along with unusual conical towers and horned passage mounds. Such architecture had no parallel in Britain, it had more in common with regions around the Caspian Sea and the Mediterranean.

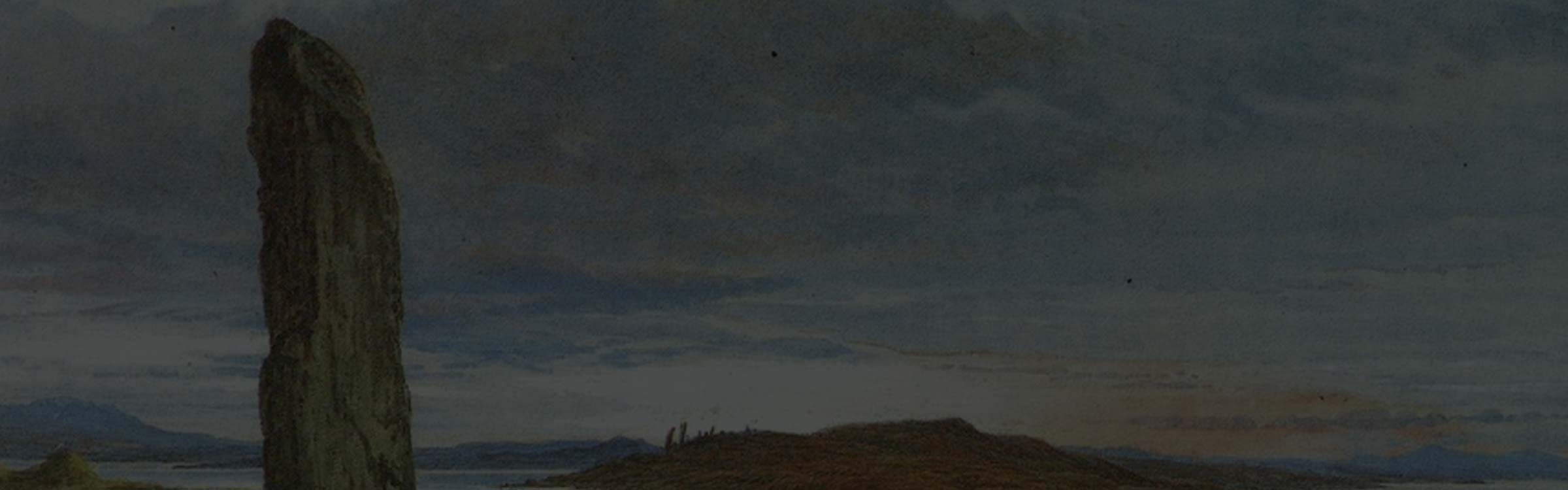

The Ring of Brodgar in Orkney, Scotland, UK (Alan / Adobe Stock)

When the first Scandinavian settlers arrived in Orkney they recorded how the builders of this megalith culture were physically different from locals, spoke a different language, wore white tunics and behaved like a priestly caste, they formed a society apart, but by the time new settlers arrived they had long vanished. All that remained were their names: the Papae and Peti. The origins of these mysterious people and the monuments they left behind, from Orkney to the Hebrides and into Ireland, aroused my curiosity for years.

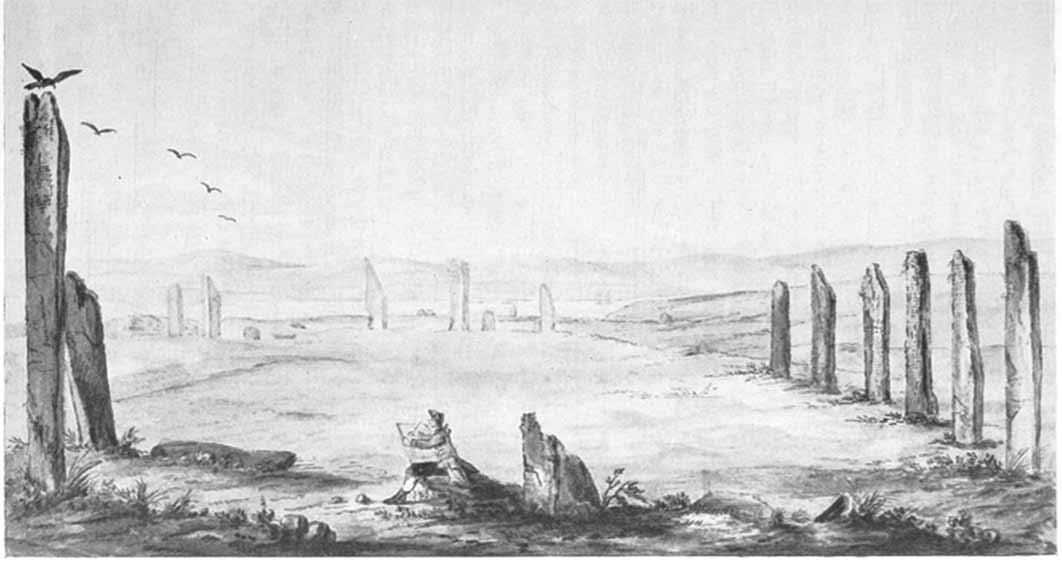

A watercolor drawing, signed John Frederick Miller, based on his pen and ink sketch of the Stones of Stennes, 1772. In Lysaght, A.M. (1974) Joseph Banks at Skara Brae and Stennis, Orkney. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London

Axis Mundi Of Neolithic Orkney

Three stone circles form the axis mundi of Neolithic Orkney. The first, Stenness, is perhaps the most impressive despite only three-and-a-half of its 11 original monoliths remaining. Unlike others of its kind, Stenness looks and feels like a machine or a place of high council rather than an object with which to measure the sky, and it was still remembered as such before the town of Kirkwall took over the role. While looking through the notes of Joseph Banks’ expedition of 1772, I came across a watercolor of a nearby monument that has escaped everyone’s attention. In the foreground, a man sits on a broken stone drawing two megaliths, one leaning on the other, while a further six stones as tall as Stenness stand behind him. There is no mistaking the position and orientation of the illustrator, he is on high ground, with Stenness itself, now merely a semi-circle, positioned in the background with the loch beyond. Between the watercolor and the accompanying survey, one is given the impression of a quadrangular stone monument, and if so, the design seems consistent with similar enclosures such as Crucuno in Carnac, Avebury in England, and Xerez in Portugal, all of which were designed to calculate the extreme rising and setting of the Sun and Moon.

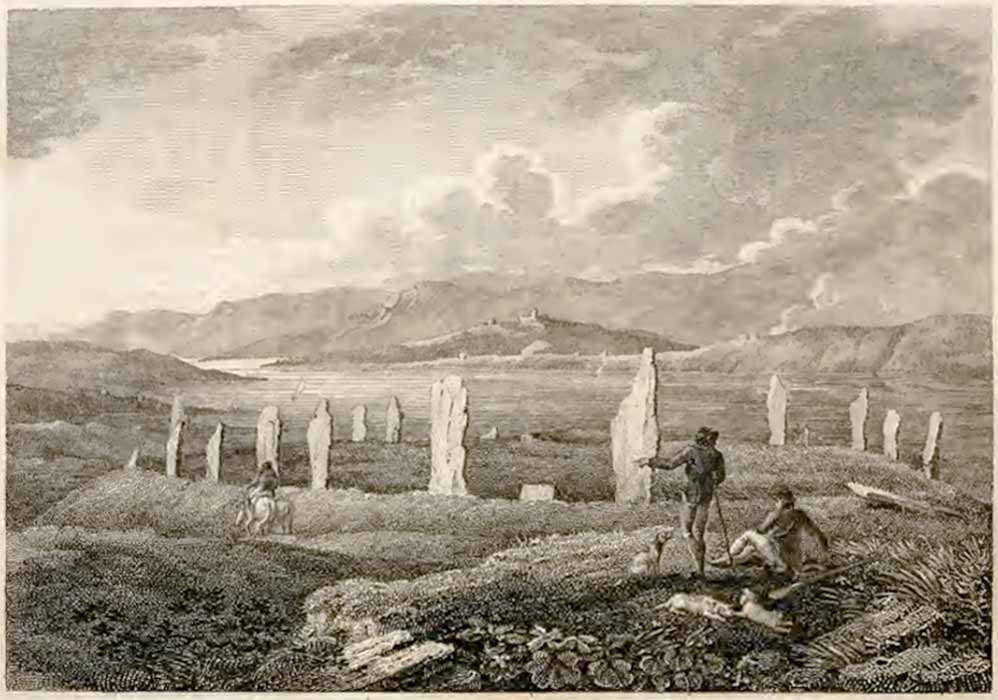

19th-century view of Brodgar by Rev. Dr. George Barry, in ‘History of the Orkney Islands’, (1805) Edinburgh

Along the narrow isthmus to the northwest of Stenness stands a more intact Ring of Brodgar, with 27 of its original 56 sandstones still upright (the number required to calibrate the solar and lunar cycles, just as with the Aubrey Holes around Stonehenge). The circle and its 12-foot-deep (3.6 meters) circular ditch were placed not on the high point of the ridge, as expected, but precisely where the 59th degree of latitude runs through the center.