Aristocratic Athenian Hero Pericles Versus Demagogue Villain Cleon

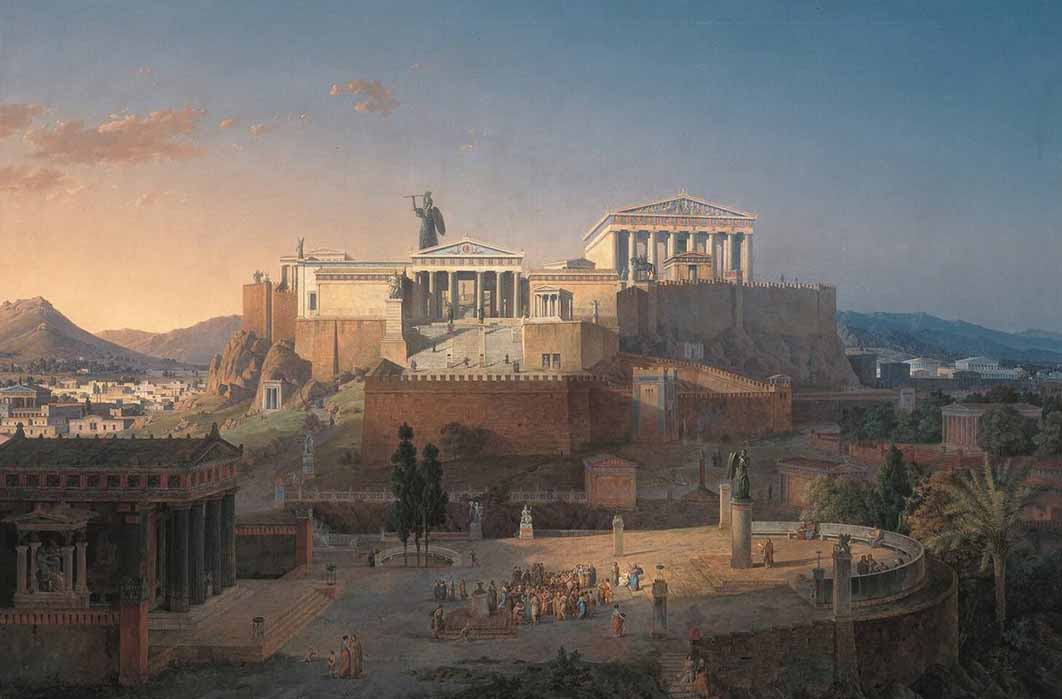

The founding of the Delian League in 478 BC moved the Athenians closer to the idea of democracy. However, although the Athenians believed that all men were created equal in political power and the notion of “the people” should ideally refer to all citizens, some individuals of the ruling elite were still set apart by their privileges.

Pericles’ Democracy

The Athenian general Pericles was acknowledged as Athens' leader for 32 years. He furthered democratic progress by attempting to compensate citizens for their political involvement. However, despite espousing the cause of the people and using his influence as a champion of democracy, ironically Pericles occupied the position of the most powerful man in Athens as the head of state year after year. Pericles enacted laws in 451 BC limiting Athenian citizenship only to legitimate sons of Athenian parents, which restricted citizenship to only a small portion of the population with little potential for growth and, consequently, less people with whom he could share a democracy. Pericles' funeral oration in 430 BC during the annual commemoration and state funeral for fallen warriors of Athens, promoted the notion that the Athenian government constitutes a majority where all people are respected, treated fairly under the law, and rewarded according to their merit. Unfortunately, this speech ignored the fact that although they made up the majority of Athens' adult population, women, slaves, and foreigners were all excluded from political life due to Pericles' legislation.

Pericles's Funeral Oration, by Philipp Foltz (1852) (Public Domain)

This did not seem to bother the historian and general Thucydides as, in his History of the Peloponnesian War, he highlighted the superiority of Pericles over his successors. According to Thucydides, Pericles not only possessed exceptional integrity and personal leadership, but he was also able to assess and influence public opinion to a large degree. By contrast, his successors were so weak by comparison that they were forced to pander to the populace to the point where they were handing over public affairs to people who were incapable of managing them.

Pericles the Hero Falters, Cleon the Villain Rises

With Sparta at the forefront of the Archidamian War in 431 BC, Pericles proposed a defensive plan. Safe behind their extensive walls, the Athenians would utilise their fleet to inflict harm on the shore allies of Sparta. Pericles reasoned the Spartans would soon realize they had to choose whether to defend their comrades and call off the attack on Athens or to press on without reinforcements. However, this was a serious mistake in judgement in Pericles’ policy as it was terribly costly and ineffectual. After the Spartans had decimated Attica, the Athenians launched attacks on multiple cities along the Peloponnesian coast and destroyed the Megarid during the first year of the war. However, their efforts were in vain, and during the Fall of 430 BC, Pericles was removed from office due to his inability to provide explanations for several financial issues in his strategies. Plutarch tells that Cleon was front and centre in levelling this accusation against Pericles, although he notes that not every historian agreed with this assessment.

- The Peloponnesian War: Intrigues and Conquests in Ancient Greece

- Visiting A Time Capsule Of Periclean Athens

- Thucydides Gave Amazing Insight into War That Shook The Aegean World for Decades

Cleon, along with General Nicias, were successful in persuading the Athenian Assembly that a more assertive stance was required when Pericles briefly regained power in the Spring of 429 BC, but died shortly after. The Spartans came to the same decision and pledged support to the islanders of Lesbos if they staged an uprising against Athens, but they broke their word. When the Athenians reestablished order in 427 BC, the Assembly was faced with deciding what to do about the rebels from the town of Mytilene.

It was agreed that Salaethus, the Spartan envoy who had promised the rebels his support, would be executed right away without a fair trial. Following this, Cleon's proposal to slaughter all the Mytilenean men and sell their wives and children into slavery, was approved by the Athenians. Although it was an extreme order, not many could have been surprised as the Spartan residents who had enjoyed special treatment inside the Athenian Empire had violated their oath of allegiance, which in antiquity was regarded as an unforgivable transgression.

When the Athenians reconsidered their decision after realising how disproportionate it would have been under the circumstances, Cleon contended that a policy of deterrence was the most effective means of averting additional uprisings. This was an outright departure from Pericles' moderate approach, which had failed to maintain the unity of the league.