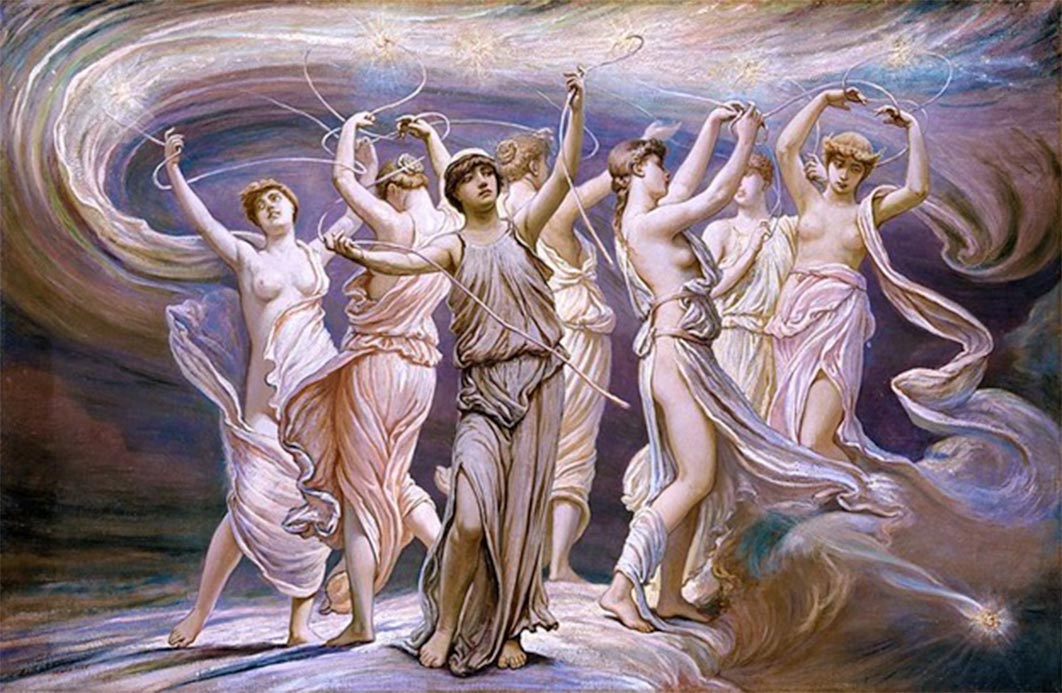

The Pleiades, Blue Print of the Seven Hills of Rome and Other Sacred Cities

Two thousand years after the death of Ovid – the Roman poet who was banished by Augustus from Rome to the remote town of Tomis on the Black Sea in 8 AD – the reason for his exile remains a mystery. Could it refer to the secret name of Rome and was it linked to a pre-historic stellar cult that built their cities on seven hills using the Pleiades – the Seven Sisters as a blue print?

Ancient Italy - Ovid Banished from Rome by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1838) (Public Domain)

Ovid’s Treason

When Ovid was condemned, he was working on the Fasti (the Festivals), a poem pertaining to the Roman calendar, explaining the origins and customs of important Roman festivals, digressing on mythical stories, and providing astronomical and agricultural information appropriate to the seasons. It was to be divided into 12 books, one for every month of the year. But when the poet was halfway through the work, he was suddenly and inexplicably condemned to exile to Tomis, (modern-day Constanța, Romania) halting his work. As he laments in the Tristia (‘Sorrows’) a collection of letters written in elegiac couplets during his exile: “I wrote it recently Caesar, under your name, but my fate interrupted this work dedicated to you”. (Tristia II, 551-552).

Augustus of Prima Porta (First Century) Vatican Museums (Public Domain)

In short, when he was forced to leave Rome, Ovid had only just finished the first six books, from January to June. It is therefore reasonable to suppose that there is a link between the sudden condemnation and what he had just written. This is corroborated by a passage from the Tristia: “These last events shattered me” (Tristia II, 99). Soon after he hints at his guilt: “Though two charges, a poem and an error, ruined me, I must be silent about the latter” (Tristia II, 207-208). Ovid provides another important clue, referring to Augustus, “whose mercy in punishing me is such that the outcome is better than I feared. My life was spared, your anger stopped short of death, o Prince, how sparingly you used your powers!” (Tristia II, 125-128). This mysterious crime, therefore, invoked the death penalty, which Augustus had commuted to exile, presumably on condition that the poet did not reveal the true reason for the sentence.

Considering all this, it would seem reasonable to seek the poet's transgression in the books of the Fasti, and especially in the last ones. One notices at the beginning of the fifth book – where the poet dwells on some possible etymologies of the name of May – Ovid lays a speech in the Muse Calliope’s mouth that narrates the background of the founding of Rome, involving the Pleiades:

“Tethys, the Titaness, was married long ago to Ocean, he who encircles the outspread earth with flowing water. The story is that their daughter Pleione was united to sky-bearing Atlas and bore him the Pleiades. Among them, Maia is said to have surpassed her sisters in beauty, and to have slept with mighty Jove. She bore Mercury, who cuts the air on winged feet, on the cypress-clothed ridge of Mount Cyllene… Where Rome, the capital of the world, now stands there were trees, grass, a few sheep and sparse huts. When they arrived, his prophetic mother said: “Halt here! This rural spot will be the place of Empire.” (Fasti, V, 81-98).