Poseidon’s Wrath: The Scourge of the Sea Peoples

Perhaps 3,000 years from now archaeologists will be debating the reasons for the diaspora that occurred in the lands around the Mediterranean Sea during the early 21st century. What would have accounted for the mass migration from the near Middle East and Africa to far northern European countries, they might ask? Would they know about the brutal civil war in Syria causing families to hastily flee with the few possessions they could carry; would they find some of the remnants of 100s of rubber dinghies that littered the shores of Rhodes? Would they consider famine and political-religious conflict in Africa causing families to hand over their life savings in desperation to pirates for sea passage? Would they find some artifacts such as a plastic doll, the last sentimental keepsake of a child that drowned in the perilous sea? About 3,000 years ago, a similar situation occurred when Poseidon, in a bout of anger, stirred the Mediterranean basin - today we still speculate as to the origins of the so-called Sea Peoples.

The Late Bronze Age

The Late Bronze Age was a prosperous era. One only has to visit the enormous palace-temple complex at Knossos (Crete), the fortified royal settlement at Mycenae (Greek Peloponnese), the magnificent Hittite capital of Hattusa (northern Turkey); the bustling near-eastern Mediterranean sea ports of Ugarit (Syria); Byblos, Sidon, and Tyre (Lebanon); the wealthy Mesopotamian cities located on the fertile banks of the Tigris and the Euphrates, such as Nippur, Ur, Lagash, and Babylon (Iran and Iraq); down to the royal residences of Memphis, Amarna, and Thebes along the Nile (Egypt), to realize they all flourished and benefitted from trade.

Hugging Poseidon’s Mediterranean coastline merchant ships traded in tin from what is today England, copper from Cyprus, Turkey, and the fertile crescent, glass, cedar, and incense from the Levant, lapis from north of the Indus valley, gold from Egypt, and ivory from Africa. But wealth breeds envy, which leads to war - and Ares challenged Poseidon’s supremacy.

The Battle of Kadesh

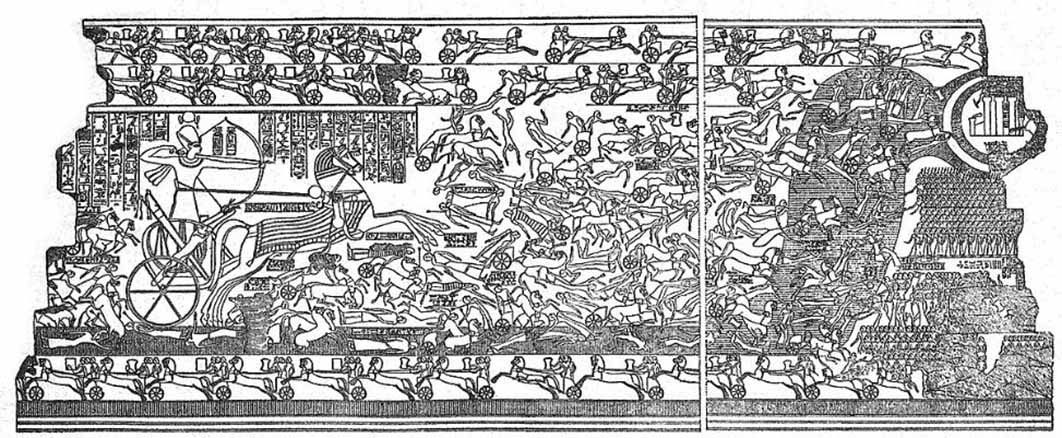

In 1274 BC the mighty Hittites led by King Muwatalli (1295 – 1272 BC) and the equally powerful Egyptians led by Ramesses II (1279 – 1213 BC) faced each other at the Battle of Kadesh (located on the Orontes river on the border of modern Syria and Lebanon). This battle is famous for being the first recorded battle where two-wheeled chariots were employed as war machines. The results of the battle are inconclusive as both sides claimed victory. The Egyptians claimed, “(King Ramesses II) cast them into the river like crocodiles, and he slew whomever he desired,” while the Hittite version reads, “at the time when King Muwatalli made war against the king of Egypt, when he defeated the king of Egypt.”

Mural in Ramesses II's temple in Tebes, depicting the Battle of Kadesh. (Public Domain)

The war, like most wars, depleted the resources of the empires, which opened the door to exterior threats. In 1280 BC, Egypt had to ward off an attack from Libya, which had formed an alliance with the Sherdans. These fierce warriors were identified as probably Mycenaeans, due to depictions of their Mycenaean horned helmets. The Sherdans settled at Akko and later bequeathed their name to Sardinia. (There is some speculation that they may have originated from Sardinia’s Nuragic civilization.) The Sherdan became mercenaries, fighting on both sides during the Battle of Kadesh. The Libyans were defeated, but they remained a menace. The rising power of Assyria in northern Mesopotamia posed a more serious threat to both the Hittites and the Egyptians, which led the previous adversaries (represented by Pharaoh Ramesses II and King Hattusilis III) to sign a peace treaty in 1269 BC, where they agreed to become allies against aggressive acts.

Assyria was a force to be reckoned with. With the capital Assur located on the fertile fields of the Tigris, the population was well fed and there was plenty of pasture for cattle. It also lay on the crossroads of west to east and south to north trade routes. Their neighbors coveted their affluence, which obligated the Assyrians to maintain a strong army to protect and expand their boundaries.

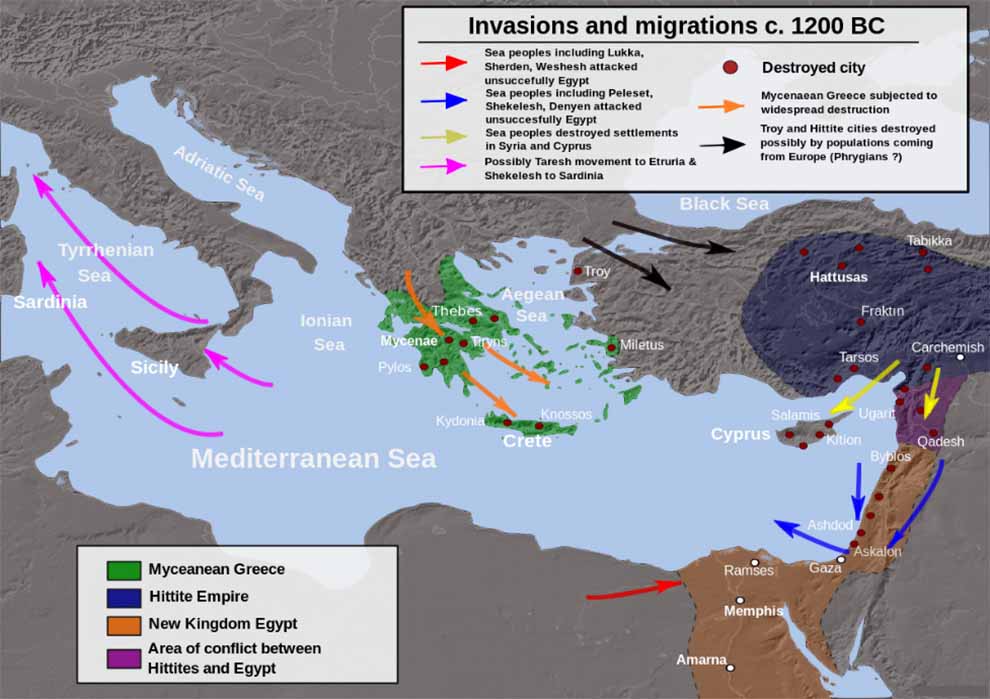

Migrations, invasions and destructions during the end of the Bronze Age c. 1200 BC. (CC BY-SA 3.0)