Procopius, Fourth Century AD Spy Who Became a Roman Emperor

Although its golden age had long passed, the Roman Empire was still a prosperous and militarily formidable state at the turn of the fourth century. The famed Pax Romana – the century between the reign of Trajan (98 - 117) and that of Severus Alexander (222 - 235), which corresponded to the apogee of Roman civilization – continued to evoke nostalgia in the collective memory of the Empire’s inhabitants. However, internal order was frequently disrupted by heated confrontations between Paganism and Christianity, as well as amongst the various nascent Christian factions themselves. The enemies of the Empire, such as the Germanic confederations and the Persians, who were undergoing a militaristic revival, were by now exerting a permanent and increasing pressure on the borders (limes) of the Empire.

Internal order was frequently disrupted by heated confrontations between Paganism and Christianity, as well as amongst the various nascent Christian factions themselves ( R. Gino Santa Maria/ Adobe Stock)

The Empire Under New Management

To counter the increased threats, Emperor Diocletian (284 - 305) established the tetrarchy, which was a system of government where authority was shared between four emperors. In addition to facilitating the management of the Empire, this system was also an attempt to rationalize the succession process by avoiding the emergence of usurpers and internal armed conflicts; an affliction that plagued the Empire during the mid-third century. For a period of roughly 50 years – between 235 and 284 – a rapid succession of 20 emperors took place in a context of military anarchy.

Decline of the Roman Military

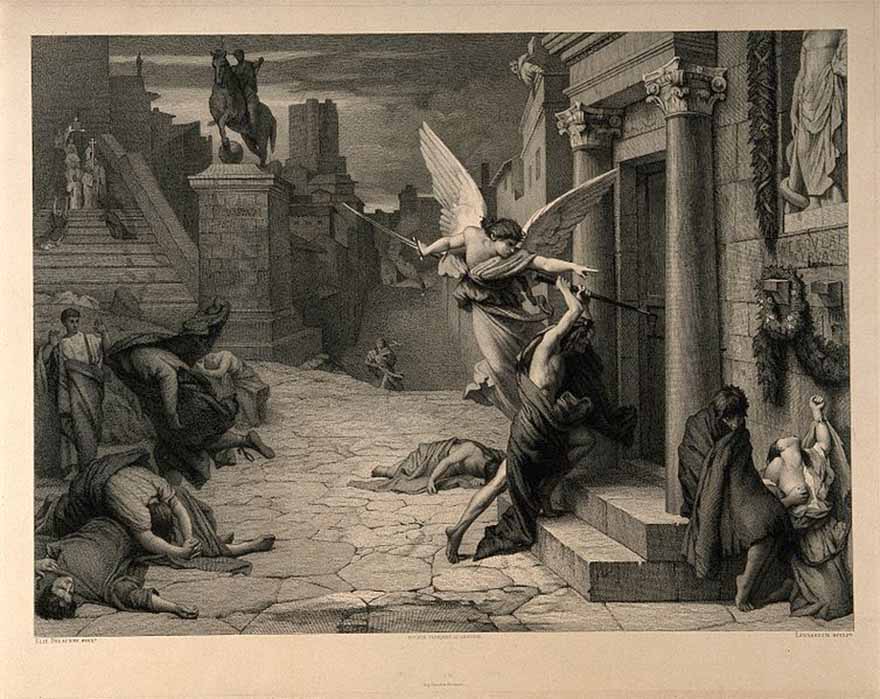

Further to the establishment of the tetrarchy and other important administrative reforms, military manpower was significantly increased. The resulting increase of military expenses had to be supported by a population that was considerably smaller compared to the century before. Essentially, the Empire’s population had emerged from the third century decimated by a long period of civil war and a pandemic. The Cyprian plague, which appeared in 251 and persisted until 270, is estimated to have caused widespread manpower shortages for food production and for the Roman army. Consequently, the population of the Empire assessed at 70 million in the middle of the second century is estimated to have fallen to around 50 million a century and a half later.

The angel of death striking a door during the plague of Rome, by Levasseur after J. Delaunay. (Wellcome Images)

By the second half of the fourth century, except for the skill of sieges, the production of weapons and the logistical support of armies in the field, the Roman war machine had definitely lost the superiority it had over its enemies and with which it was able to adequately defend a powerful and prosperous Empire for centuries. As A. Goldsworthy rightfully states in his 2000-book entitled Roman Warfare: “By the fourth century the Roman army found itself more often as the defender than the attacker in siege operations and had developed the skill of defence to a high art”.

Decline of the Roman army ( vukkostic/ Adobe Stock)

By the time Constantine I’s reign began, most legionaries were Romanized foreigners or their descendants. Since the beginning of the fourth century, a soldier’s career path was passed down from father to son by imperial decree because of the lack of recruits. The profession of soldiering had become so unpopular in fact that by the end of the fourth century, the practice of self-mutilation was widespread. Sources during that period have reported that it was common for potential recruits to cut off a thumb so they would be unable to bear arms. To make up for the shortfall, the Roman authorities had to hire an ever-increasing number of mercenaries and large groups of non-Romanized Germanic fighters in the Roman army, which ultimately undermined its military cohesion. Roman authorities and generals were increasingly forced to rely on every conceivable form of diplomacy, deception and a range of clandestine activities to ensure the survival of the regime, a role that the army was no longer able to assume by itself. This included espionage.