Ramesses III, The Final Warrior Pharaoh: Savior of Egypt in Her Darkest Hour—Part I

The reign of Ramesses III proved to be unprecedented in more ways than one. While most of his predecessors often had to thwart the designs of Egypt’s enemies one at a time, he had to quell invasion attempts by a coalition of savage forces on land and water. As the marauding Sea Peoples set their sights on the grandest prize, Ramesses realized that he had to make a bold statement as Pharaoh and prove that he was God on earth by annihilating their foes.

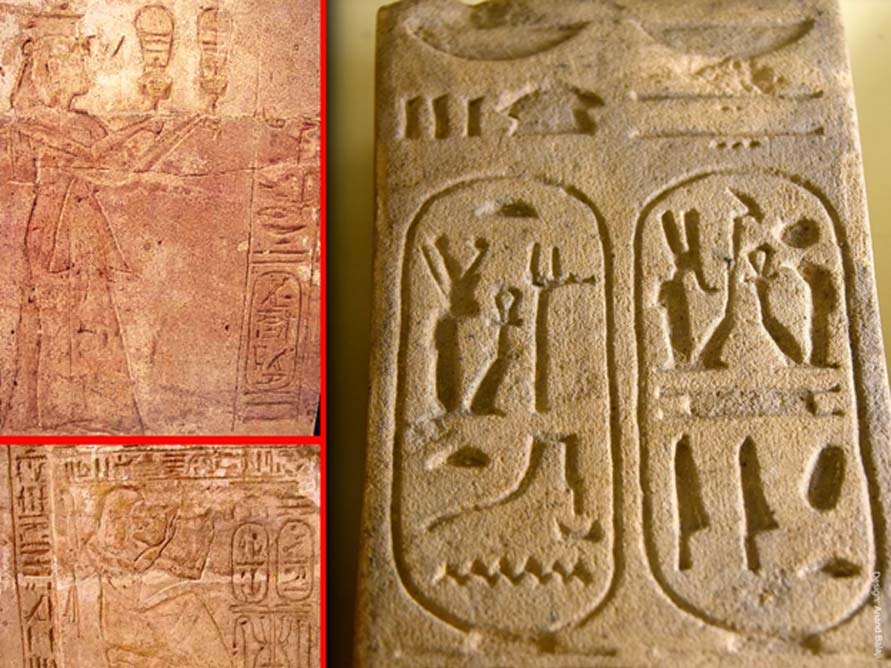

A damaged relief from his palace-cum-mortuary temple at Djamet shows King Ramesses III making offerings to the gods. Medinet Habu. This edifice played a vital role during the king’s reign and was the place where he breathed his last following an attempt on his life. (Photo: Elena Pleskevich/CC BY-SA 2.0)

A Robust Dynasty Withers Away

Egypt entered an era of extreme uncertainty at the close of the Nineteenth Dynasty. Down to this day, the mystifying power tussle that played out between two kings – Amenmesse and Seti II – when they ruled Upper Egypt and the Delta region up to Memphis, respectively – after the death of Pharaoh Merenptah (ca. 1202 BC) the 13th son of Ramesses II; continues to confound scholars. In due course, Seti II, the rightful heir to the throne ousted Amenmesse and decreed a damnatio memoriae against the usurper. However, he was to rule for no longer than a couple of years. Upon his demise, young Merenptah Siptah was placed on the throne by chancellor Bay – a master manipulator or ‘kingmaker’ of Syrian origin. It is possible that Siptah was the son of the rebel ruler Amenmesse and not of Seti II. A statue of Siptah in Munich shows the Pharaoh seated on the lap of his father, whose image has been thoroughly destroyed.

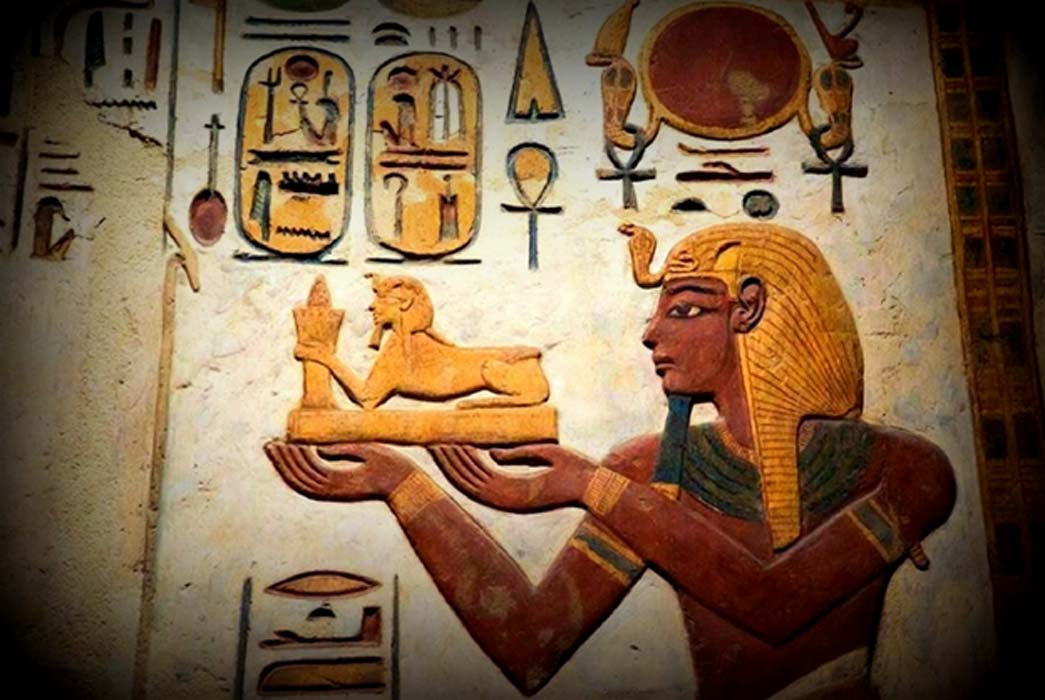

This elegant quartzite head wearing the Blue Crown originally belonged with the body of a statue that still stands in the great Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Amun at Karnak; the inscriptions show that it had been carved for the short rule of King Amenmesse. Following Merenptah, Amenmesse had apparently seized the throne from the rightful heir, Seti II who was subsequently able to retake the throne. Later, he reinscribed this statue, like most of the others carved for Amenmesse, with his own name. (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Dr Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton believe this damaged figure represented Amenmesse: “The only ruler of the period who could have promoted such destruction was Amenmesse, and likewise he is the only king whose offspring required such explicit promotion. The destruction of this figure is likely to have closely followed the fall of Bay or the death of Siptah himself, when any short-lived rehabilitation of Amenmesse will have ended.”

Anyway, Bay, who had his own devious agenda, was clearly not intent on doing anybody a favor, least of all to Siptah, who suffered illness and physical deformity. Instead, by getting him crowned king, the Syrian machinator aspired to pull the strings of power from the shadows and, in effect, become the de facto ruler of the country. Riven by petty politics, usurpation of high office, and perfidy; this period witnessed the epitome of intrigue when Queen Twosret, one of the few women rulers of ancient Egypt, assumed the throne.

In Regnal Year 5 of Siptah, this widow of Seti II ousted the vile chancellor Bay and promptly had him executed. Subsequently, when the sickly Siptah died within a year, Twosret, his step mother declared herself sole pharaoh.