Robbing Tutankhamun: Ransacking the Royals and Decline in Tomb Security – Part 1

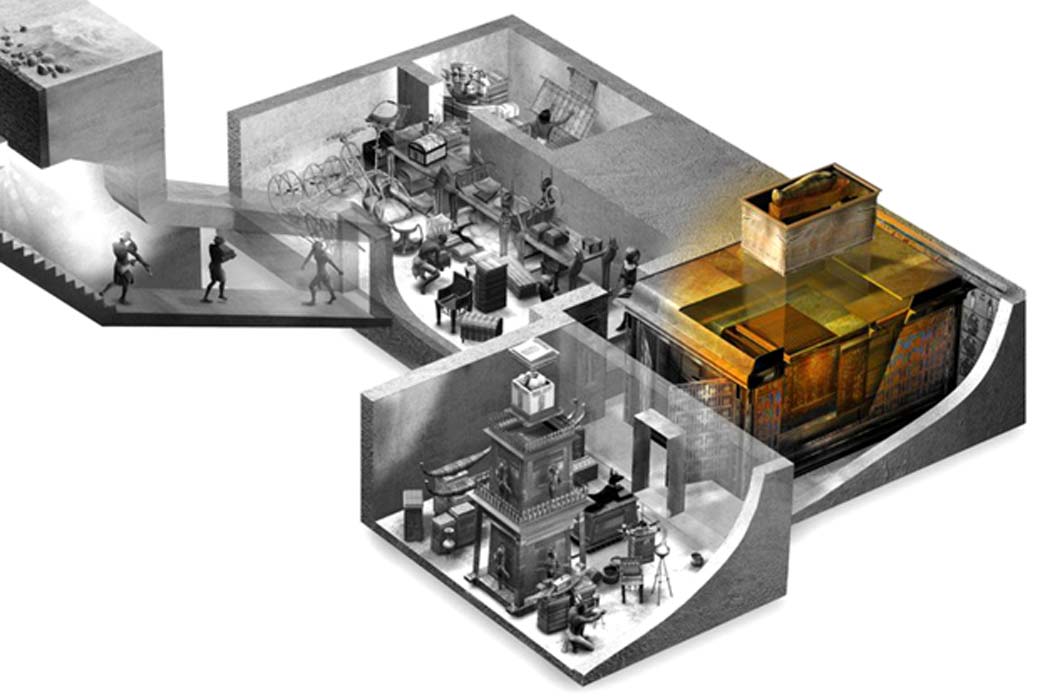

Pharaohs built lavish sepulchers equipped with all manner of security arrangements that were aimed at misleading tomb robbers. However, more often than not, the elaborate ploys of esteemed architects to hoodwink plunderers came-a-cropper. The looters most probably comprised the very band of workers who had built or stocked the tomb, and therefore, knew the layout and exact location of precious objects. KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun too was no stranger to robberies – suffering two in quick succession. But, thanks to swift action by Necropolis officials and possibly an act of nature, his burial and the treasures within were forgotten for over 3,300 years.

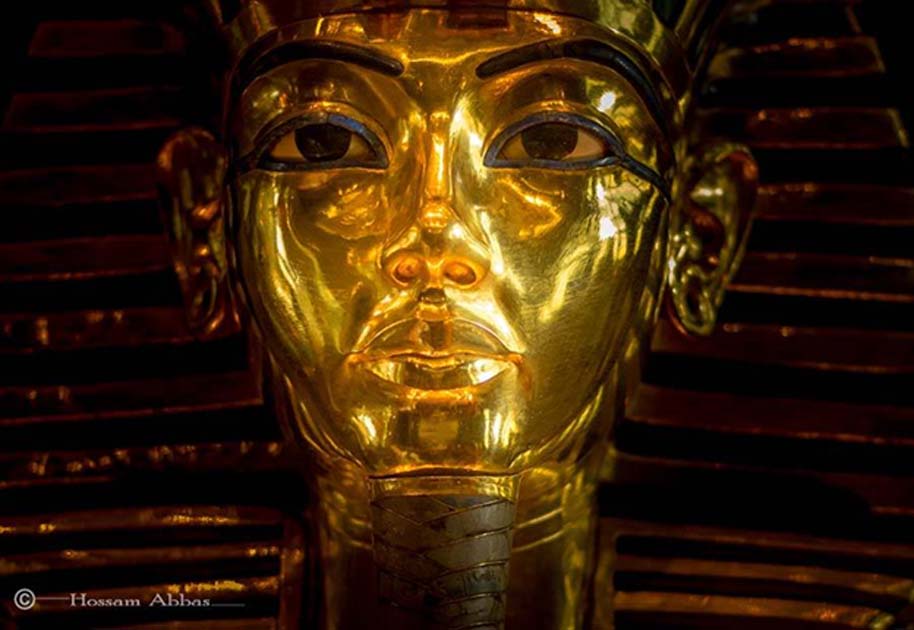

Tutankhamun, whose world famous funerary mask is pictured here, was buried with an astounding hoard of golden treasures that acted as a magnet for tomb robbers within weeks after KV62 was sealed. Thankfully, both breaches were noticed in time, the robbers apprehended and the crypt re-sealed—which preserved the precious objects until 1922. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Plundering the Great Field

Renowned French Egyptologist, Sir Gaston Maspero, once observed: “Nothing is rarer now in the Theban necropolis than virgin tombs.” He was echoing a sentiment expressed by the archaeologists not just of his day, but our era too. Even the American financier Theodore M. Davis, like the Italian explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni before him, was also left in no doubt that the Valley of the Kings had been picked clean: “I fear that the Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted”, he said – and yet, his declaration proved to be unfounded. Over the decades, several factors have been cited and studied by scholars for the lack of intact burials; but none compares with the all-important reason: tomb robbery.

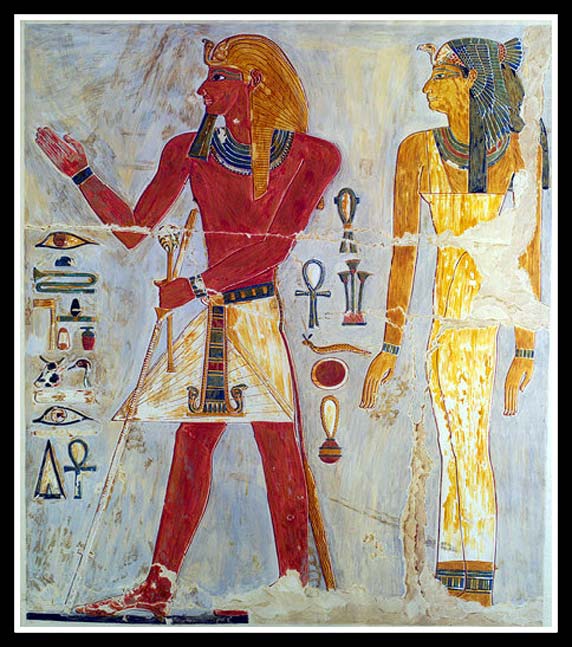

Unable to thwart the attempts of vicious grave robbers despite employing the best and apparently fool-proof measures; the kings of Egypt were eventually forced to abandon the construction of monumental sepulchers in which to house their mortal remains. Their ancestors had built pyramids, which have been likened to ‘giant come-rob-me-signs’ today. A remote and secure location was desperately sought to inter the royal dead. It was to be a ‘none seeing and none hearing’ location as indicated by the New Kingdom architect Ineni, who served under Pharaoh Thutmose I - the first ruler to be buried in the Valley of the Kings (in KV38, though this has been subject to much debate) in a cartouche-shaped funeral chamber. The decisive move this king – the father of Pharaoh Hatshepsut – made held his successors in good stead for half-a-millennium (Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties).

Thutmose I and his mother Seniseneb are depicted in this painted relief from the Chapel of Anubis in the mortuary temple of Pharaoh Hatshepsut. This is a facsimile by Nina de Garis Davies (1881–1965). Tempera on paper. Deir el-Bahri. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Sumptuous tombs carved deep into the limestone cliffs in the rambling Theban Hills came to host the largest concentration of bullion-rich burials the world has ever known. But even the crypts here — with their decoy blockings, false passages, trap-doors, well shafts and hidden rooms — only served to delay the robbers, not to scuttle them. Over millennia, whether it was the doing of individuals in groups, or even those who acted at the behest of the state, their activities stripped many tombs of royals and nobles of their riches both in the Valley of the Kings and Queens.

Comprising two valleys: the East Valley (where the vast majority of royal tombs are situated) and the West Valley; the true splendor of Ta-sekhet-ma’at (the Great Field) and Ta-Set-Neferu (The Place of Beauty) blossomed in the bowels of the earth. In an inconceivable feat of engineering that remains unmatched down to this day, the ancients carved a stunning maze of corridors running for miles in all directions.