Entoptic Imagery in Prehistoric and Pre-Industrial Rock Art

Throughout the world, prehistoric and pre-industrial shamanic cultures have rendered painted imagery onto rock faces; often in deep cave systems, but also in above-ground shelters. This rock art ranges in date from Palaeolithic designs in Europe, Australia and Asia through to the near-contemporary images of the San culture in southern Africa and the designs of indigenous cultures of North America and the Amazon basin. Until the mid-20th century the consensus anthropological view was that the rock art — while probably having magical meaning to the people who painted it — represented scenes from the natural environment, such as people, animals and landscapes. But as a greater anthropological understanding of indigenous shamanism developed, most especially through the work of Mircea Eliade and his 1951 publication Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, a new awareness evolved that the rock art produced by indigenous cultures might be the artistic result of shamanic processes, preeminently those brought about by inducing altered states of consciousness.

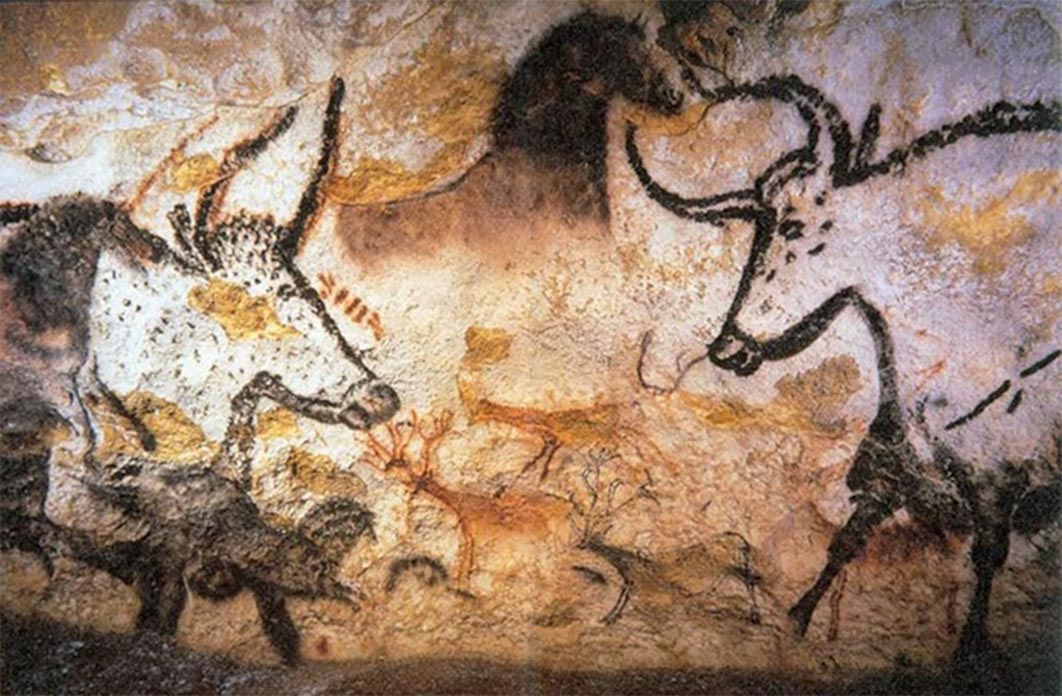

Megaloceros with line of dots (Public Domain)

The Trailblazers

This was mainstreamed in 1988 by the anthropologists David Lewis-Williams and Thomas Dowson in their paper for Current Anthropology: ‘The Signs of all Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic Rock Art’. They advance a neuropsychological model for analyzing the motifs of parietal art of this period, proposing that the geometric images are in fact artistic representations of universal optical patterns, intrinsic to the human visual system, once perceived by our shamanic ancestors during altered states of consciousness. The most important element of this model is the entoptic imagery displayed in the rock art and how it matches closely the geometric patterns seen by people in modern clinical conditions who have altered their state of consciousness.

The Entoptic Model

The word ‘entoptic’ derives from the Greek ἐντός ‘within' and ὀπτικός ‘visual’. Entoptics usually consist of geometric patterns seen as overlays in the visual horizon. These patterns may be an array of dots, parallel lines, labyrinths, zig-zags, waving lines, etc. Sometimes they appear detached from the visual surroundings while at other times more integrated. Entoptics are usually experienced during altered states of consciousness, which may be achieved through a variety of means. The best evidence for the consistency of visual entoptics comes from clinical trials (from the 1950s onward), which analyzed subjective narratives of people who were administered a variety of psychedelic substances. Many of these narratives described the geometric entoptics as antecedents to deeper experiences, as if they were a geometric gateway to the main substance of the experience. The entoptics were, in effect, neuropsychological codes for signaling change in the state of consciousness.

Entoptic patterns and humanoids, Rock Art at Altamira Cave Spain, where entoptic patterns have been identified. (Museo de Altamira y D. Rodríguez /CC BY-SA 3.0)

Lewis-Williams and Dowson’s model took sketches made by people experiencing consciousness modification via psychedelic drugs in clinical trials and applied the imagery to the rock art produced by indigenous tribal communities in modern day South Africa, the Amazon and by the Native American Shoshonean Coso culture of the California Great Basin. The geometric images demonstrated extensive similarities. The rock art contained many of the geometric motifs recorded by modern trial results. These entoptics appeared to be some universal code, experienced and recorded by both modern-day psychonauts and people in indigenous communities experiencing altered states of consciousness through a variety of methods. Because the San and Coso indigenous peoples are verifiable shamanistic cultures, able to describe the meaning of the rock art of their immediate ancestors from personal viewpoints, Lewis-Williams and Dowson took their descriptions of entoptics at face value. Whether through the consumption of psychedelic compounds or dancing in a ring for hours (the San’s primary way of entering an altered state of consciousness), people in these cultures were entering a divergent reality and sometimes they recorded this reality in rock art. Much of this was composed of entoptic imagery.

A sandstone slab at Twyfelfontein, Namibia. The animals are the older engravings, overlaid by the circles (mike/CC BY-SA 2.0)