Sociae Mimae: Ancient Roman Actresses Doing It For Themselves

When Thespis, a Greek performer, stepped on the stage in 534 BC and became the first known man to speak words as a character in a play or a narrative, he broke the tradition where ancient Greek legends were only expressed in songs, dances and third-person storytelling. However, for hundreds of years after Thespis’ first appearance as the first recorded actor, the words ‘actors’ or ‘thespians’ strictly referred to men, as women's presence in the theatre remained the exception rather than the rule.

A Maenad and a Satyr, ancient Roman floor mosaic depicting Dionysiac scenes (220 AD) Römisch-Germanisches Museum Cologne (CC BY-SA 2.)

Denying Dionysus’ Cult

Women appearing on stage were not deemed decorous as women's perceived realm was the home and theatre was based on religion and sacred rites, performed in very public places. This is ironic given that ancient Greek theatre arose from the cult of Dionysus, the god of ecstasy whose rites were primarily performed by women singing and dancing, gripped in euphoric trances, in very public places. Rituals associated with Dionysus’ worship embodied the very concept of freedom and wild abandon, marked by maniacal dancing to the sound of crashing cymbals and loud music. The revellers whirled, screamed, and incited each other to ascending heights of ecstasy. The goal of this rite was to achieve such ecstasy that the celebrants' souls would be temporarily freed from their earthly bodies, allowing them to meet with Dionysus and taste what they would be experiencing in eternity. However, when these rites became formalized in the theatre, the wild women were ejected off the stage and their roles were usurped by men.

Mosaic with two actors in a tragic scene. Antikensammlung Berlin ( Marcus Cyron /CC BY-SA 3.0)

The ban on women on stage, instituted by the Greeks and later reinforced by the Christian concern of female chastity, lasted until the 17th century when female vocalists first appeared in operas. Even this new development did not sit well with Christian authorities. “A beautiful lady who sings on stage and retains her chastity is like a man who leaps into the Tiber and keeps his feet dry,” Pope Clement XI observed, describing the ancient men's enduring anxiety of seeing their wives on stage or, possibly, in public locations. “Marry a virgin so you may teach her good ways” Hesiod wrote in his Work and Days. Thus, women who were not virgins were considered wild and barbaric, unless they were tied into a marriage and kept in a husband’s house.

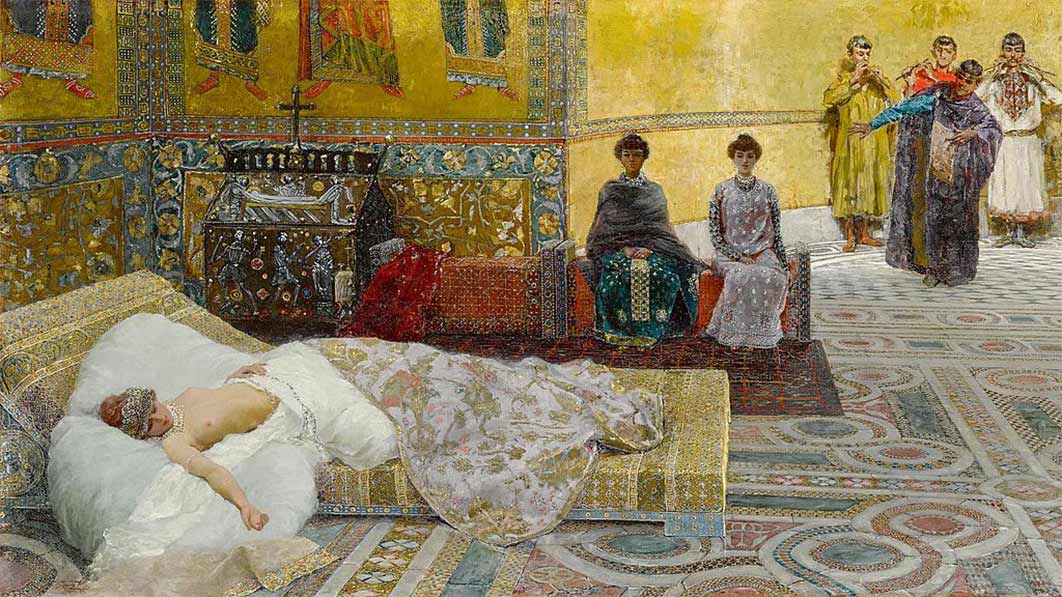

Paragon of Roman virginal virtue, Feeding the Doves by Stefan Bakałowicz (Public Domain)

Roman Disdain Of Actors

Nonetheless, the ancient Greeks adored the theatre, and ancient Greek actors were held in high regard. In ancient Rome, however, although entertainment and drama were both adored, theatre performers were mostly derided by upper-class society and regarded as morally impure. The emperor Tiberius, who ruled Rome from 14 to 37 AD, was not a very moral person himself, but he saw it fit to advise high society and theatrical actors to avoid mingling with each other. Later, Julian the Apostate, who reigned from 361 to 363 AD, forbade pagan priests from attending the theatre, thus ensuring that the players and the theatre itself were not elevated in status as a result of their presence.