Octavian’s Trolling and Propaganda Against Mark Antony

In 1493, the invention of the Gutenberg printing press dramatically amplified the gathering and dissemination of news. However, this innovation came with a dark side as it later delivered the Great Moon Hoax of 1835. The Great Moon Hoax was the first-large scale news hoax in which the New York Sun published a series of articles about the discovery of life on the moon. The articles were falsely attributed to Sir John Herschel, one of the best-known astronomers of that time, and were published complete with illustrations of humanoid bat-creatures and bearded blue unicorns. But this was not the first time that disinformation and propaganda featured in human communication. It played a major role during the first century Roman BC in the battle of words between Octavian and Mark Antony.

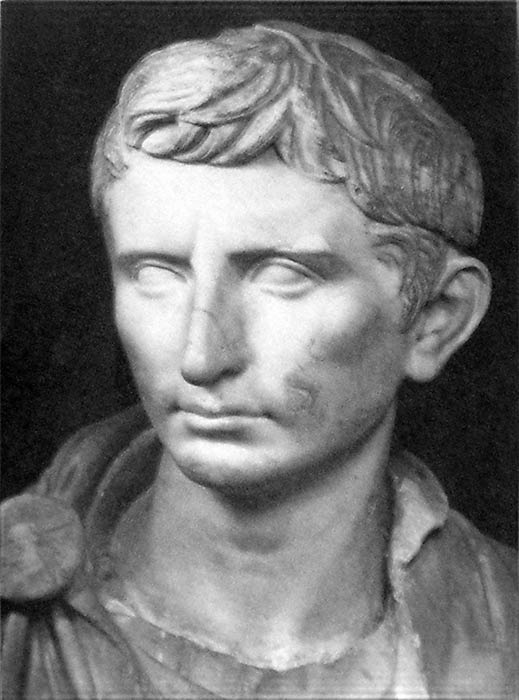

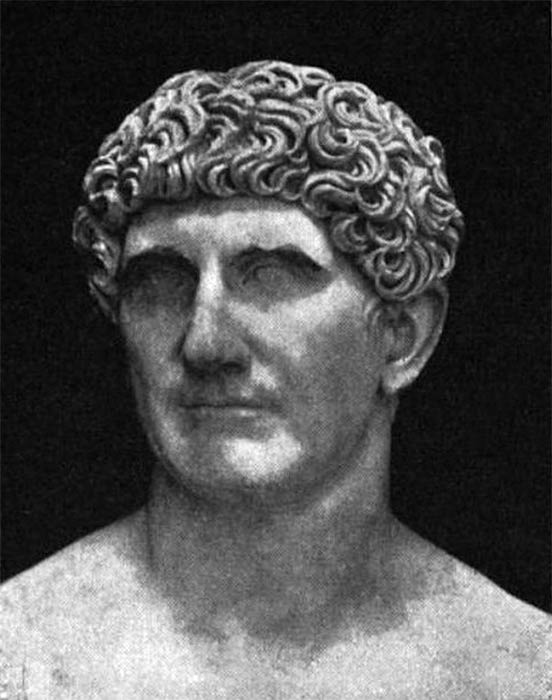

A reconstructed statue of Augustus as a younger Octavian, dated c. 30 BC (Public Domain) and a Roman bust of the consul and triumvir Mark Antony, Vatican Museums (Public Domain)

Treachery In The Triumvirate

Apart from using biographers and their narratives to discredit the reputation of the Roman general Mark Antony, his nemesis Octavian, the adopted heir of Julius Caesar, also waged a propaganda war in the form of brief, sharp slogans written on coins to portray Antony as a womanizer and a drunk. Through his use of propaganda, Octavian also implied that Mark Antony had been corrupted by his affair with the Egyptian queen Cleopatra and had become Cleopatra’s puppet. This early deployment of a disinformation campaign allowed Octavian to impact the republican system once and for all and to such an extent that it led to him becoming Augustus, the first Roman Emperor.

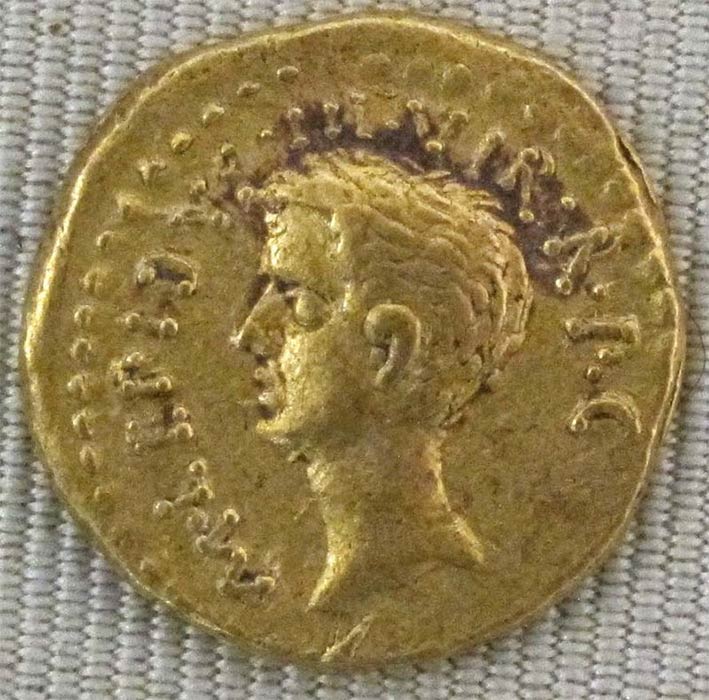

Aureus of Lepidus, c. 42 BC (I, Sailko/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

When Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon and emerged victorious over Pompey following a turbulent period of generals vying for power, he teased his citizens with the appearance of stability. However, this joy was short-lived as it ended with Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC. A year later, on 27 November 43 BC, Octavian, General Mark Antony and the Pontifex Maximus Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, formed a political alliance (the Second Triumvirate) to declare war on Caesar’s assassins and restore order in Rome. Formally called tresviri rei publicae constituendae (the Triumvirate for Organizing the Republic), the alliance was meant to last for two five-year terms. However, unlike the earlier alliance between Julius Caesar, Pompey and Crassus (the First Triumvirate) which was a private arrangement among three men, the Second Triumvirate was an official, legally established institution, which vested the three men who formed it with dictatorial powers.

- What if Cleopatra and Octavian Had Been Friends?

- The Life and Times of Mark Antony, Caesar's Trusted Aide

- Political Intrigue: The Fake News that Sealed the Fate of Antony and Cleopatra

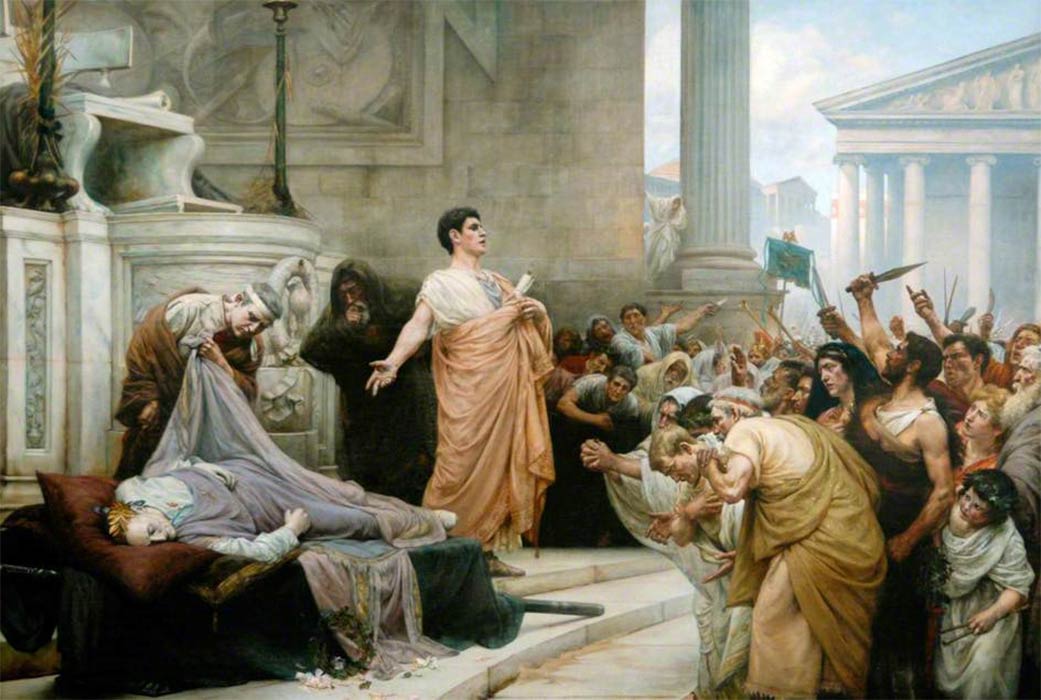

After this formation, Antony travelled to the east to prepare for his invasion of Parthia while Octavian mostly positioned himself in and near Italy. To progress on his own, Octavian would have to establish himself as being the rightful successor of Caesar as well as being able to take on the leadership role in future. However, Octavian would have to accomplish it by maintaining the appearance of continuing a republican form of government instead of establishing a kingship. Cicero tells of a speech by Octavian before the Senate near the end of 44 BC in which he dramatically pointed to a statue of Julius Caesar and said, “So may I attain the honours of my father.” This motion and mere few words tell of Octavian’s early mastery of propaganda in this political context. With a simple, dramatic motion and declaration, Octavian conveniently glossed over not only Julius Caesar’s own authoritarianism but his own authoritarian ambitions as he theatrically defined the next chapter of his political life as that of filial piety and honour instead of personal ambition.

Marc Antony's Oration at Caesar's Funeral" as depicted by George Edward Robertson (Public Domain)