The Severan Emperors and the Demise of the Roman Senate

By 190 AD, the debauched life of emperor Commodus had reached a sinister summit. Never had the Roman Empire been led by such a disgraceful character. Probably mad, he identified himself with the god Hercules and tried to imitate him in every way imaginable, even in the arena. His attitude of suspicion and unhealthy anxiety concerning his personal security were responsible for attacks against the aristocracy and senate members. In 192, Commodus was strangled after a failed poisoning attempt. His death marked the end of the Antonine dynasty of Roman emperors. Following two ephemeral reigns, the Severan dynasty of emperors was established, and it would lead the Empire until 235.

During this period, the economic situation of the Empire was generally good although we witnessed the introduction of new taxes and the disappearance of important exemptions reserved for the aristocracy. The currency began to lose its value and its circulation decreased. The scarcity of precious metals and the decline in trade were undoubtedly among the causes. On the other side of the frontier (limes), the growing population of the Germanic tribes, which in contact with the Romans had begun to organize and settle down, created an ever-increasing pressure on the Empire’s defence apparatus. This permanent threat of invasion already visible under the reigns of emperor Marcus Aurelius and Commodus became one of the major concerns of the Severan emperors. From that point on, this new reality inevitably affected the history of the Empire until its fall in the West two and a half centuries later.

Septimius Severus (193-211)

Following the assassinations of emperor Commodus and then of emperor Pertinax, Didius Julianus was appointed emperor in particular circumstances, the sacred role of emperor being adjudicated by the Pretorian Guard to the highest bidder. The Senate, recalcitrant, but faced with a fait accompli, confirmed him in his new functions. Three governors acclaimed as emperors by their own armies rejected the choice of Didius Julianus. Septimius Severus, who was closer to Rome than the other two contenders, immediately made his way to the capital with an army to face Didius Julianus. Once the latter was defeated and then assassinated, a new turbulent reign began.

Septimius’s career path did not differ greatly from those of his predecessors. The first emperor born on the African continent was a member of the equestrian order when he was admitted to the senatorial order by Marcus Aurelius. Proconsul of Africa in 174, he then became proconsul of Sicily in 189, and then governor of Pannonia under Commodus. Once donning the purple cloak, Septimius retracted his promise not to crack down on the Praetorians who had supported and fought for Didius Julianus. After executing those who had assassinated Pertinax, Septimius dissolved the Praetorian Guard and dispersed its former members to reconstitute it immediately with members of his own army. From that point on, access to this elite corps, previously reserved almost exclusively for the best Italian legionnaires, was extended to provincial soldiers.

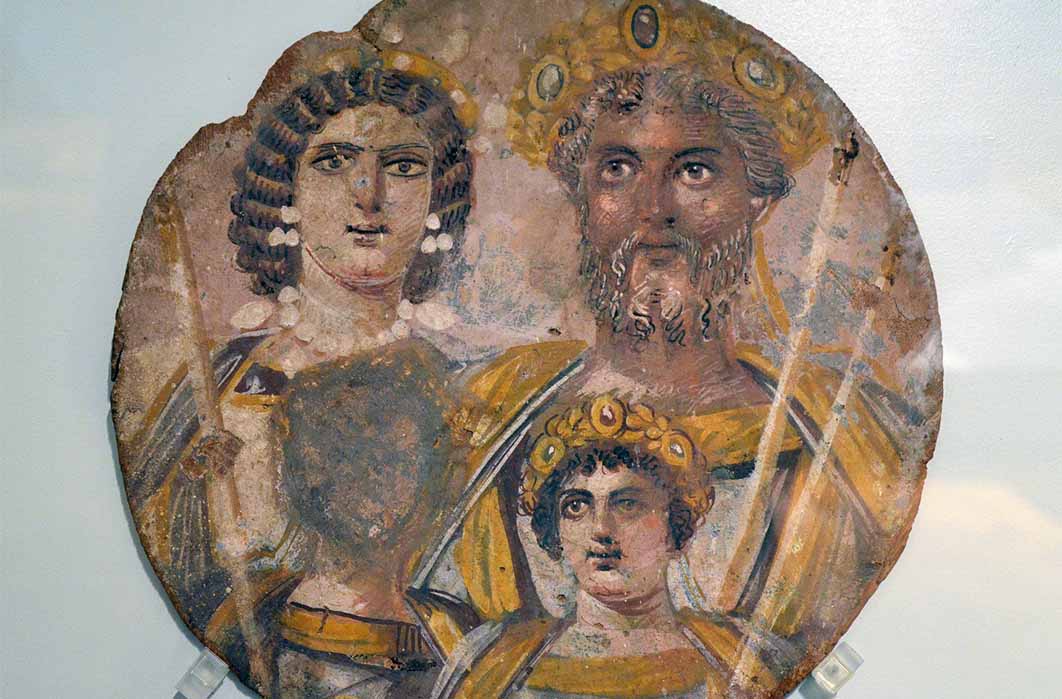

Golden bust of Septimius Severus. (Ggia / CC BY-SA 4.0)

An intelligent administrator, possibly tinged with a taste for literature and philosophy, Septimius was better renowned for his spitefulness and for his reign as an absolute monarch. His obstinacy in reigning without sharing power made him a persecutor of the aristocracy and the Senate, already battered under Commodus, from which he wrested important segments of its authority.

The first part of Septimius’s reign boiled down to the consolidation of his position. After a fifteen-month struggle, he succeeded in eliminating the threat of the pretender to the purple cloak, the governor of Syria, Pescennius Niger, at the Battle of Issus in 194. The second pretender, the governor of Britannia (England), Clodius Albius, was also defeated at the Battle of Lyon in 197. The wars of consolidation barely over, Septimius had to return to the East in order to keep in check the Parthians, who were again threatening the border. The emperor remained there until 199 to strengthen the defensive system of the region and to secure the allegiance of the provinces that had been loyal to Pescennius Niger.

The founder of the Severan dynasty began to properly reign in 202. Now that peace had returned, Septimius proceeded to reform Roman law in order to make it more accessible and less rigid. He restored a certain balance in the imperial budget despite the expenses due to the long wars, to new constructions and to the ‘deficit’ inherited from Commodus. The imperial finances were straightened out thanks to wise administration, to the entry of new sums generated by the confiscation of the goods of Albius and Niger, and to the booty accumulated during the campaign against the Parthians.

For the first time in the history of the Empire, a legion was permanently stationed in Italy. The emperor wanted to prevent experiencing the same fate that many of his predecessors had. Indeed, faced with an invasion of Italy by a contender for the purple cloak, many emperors had found themselves defenceless in Rome. Septimius repeated to his two sons, Caracalla and Geta, whom he had associated to power, that the soldiers needed to be well-taken care of, whatever the cost. In that vein, the condition of the legionary was improved. Reigning as an absolute monarch, Severus ensured the loyalty of the army on which his authority rested entirely. Salaries and privileges for soldiers were increased, and soldiers could now marry and start families during military service. Permanent settlements then began to form around the legionary camps all along the frontier from which many future European capitals would emerge.