In the Shadow of Nakhtmin: The Unfortunate Crown Prince of Egypt

No other period in ancient Egyptian history had its share—almost a surfeit—of enigmatic and poorly understood characters as the Amarna era. Mysterious kings and queens apart, Nakhtmin, a generalissimo-turned-crown prince was a key player. An oft-overlooked figure, his life and death had a tremendous bearing on the unquiet events of the late-Eighteenth Dynasty.

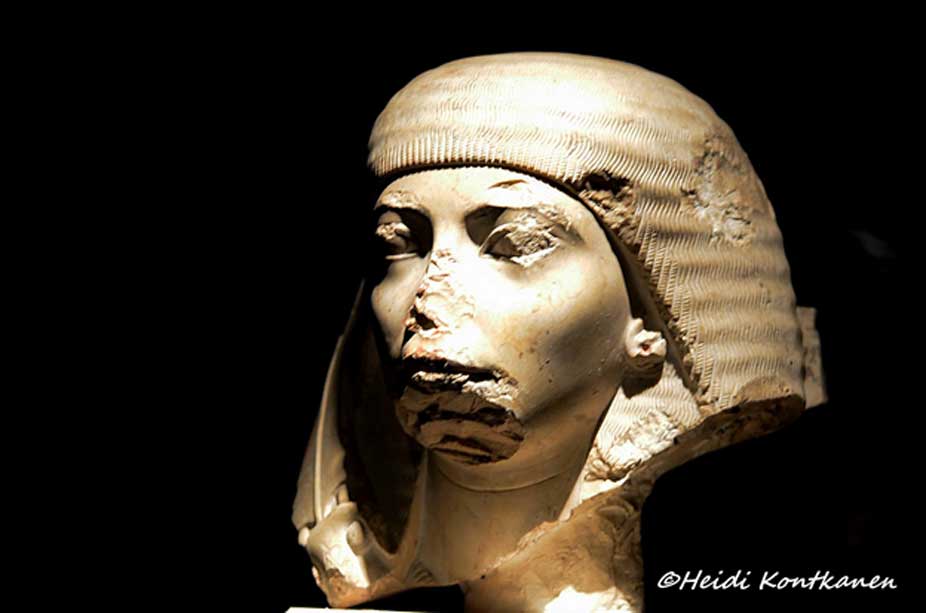

This head of indurated limestone is a fragment from a group statue that represented Amun seated on a throne, and Tutankhamun standing or kneeling in front of him. All that remains of the god is his right hand, which touches the back of the pharaoh’s crown in a gesture that signifies his investiture as king. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Mystery of Lineage

There is no clear-cut answer to the background or origins of Nakhtmin (also called MinNakht). This person springs into view in spectacular fashion, only to vanish without a trace shortly thereafter. It was speculated that there were three individuals by this name during that time; but we can now be certain that two of those names actually referred to this Nakhtmin alone. Evidently close to the ruling pharaoh, Nebkheperure Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema, Nakhtmin was a military commander under him. (Another “Nakhtmin” was married to Mutemnub, the sister of Ay’s wife Tey; and the couple had a son named Ay, who went on to become the High Priest of Mut and also the Second Prophet of Amun.)

This head, part of a fragmentary monolithic pair statue of husband and wife, represents Nakhtmin, a royal scribe and general under Tutankhamun. He was designated the crown prince when King Aye came to the throne. Along the right-hand side of the wig can be seen the remains of the ostrich plume fan that served as a symbol of his rank. Luxor Museum.

Further proof of Nakhtmin’s extraordinary status in the royal court can be gathered from the prestigious titles that were bestowed on him; and these included: “the true servant who is beneficial to his lord, the king's scribe,” “the servant beloved of his lord,” “the Fan-bearer on the Right Side of the King,” and “the servant who causes to live the name of his lord.”

This elegant statue fragment of an unnamed woman is made of crystalline limestone. It originally formed a double with what is left of her husband, the army general Nakhtmin’s head (now at the Luxor Museum, pictured above). Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Given his almost sudden elevation, it is therefore possible that Nakhtmin had not risen up the ranks over several years to the official positions he enjoyed; but was associated with a powerful family or individual. This, if true, paved the way for him to earn illustriousness effortlessly. All of this in no way seeks to diminish his probable contributions, or the possibility that he attained great heights in his career by sheer dint of hard work.